'No Sabo Kids'? From insult to badge of pride for young Latinos

Hope Gomez heard stories growing up about her Mexican American grandmother getting hit for speaking Spanish at school, a punishment dispensed by American teachers to force Latino students to speak only English.

But for as long as she can remember, Gomez has experienced the opposite. She's been shamed, ridiculed and humiliated by fellow Latinos for not speaking Spanish, harsh treatment that Gomez says makes her feel "like I'm not Latino enough."

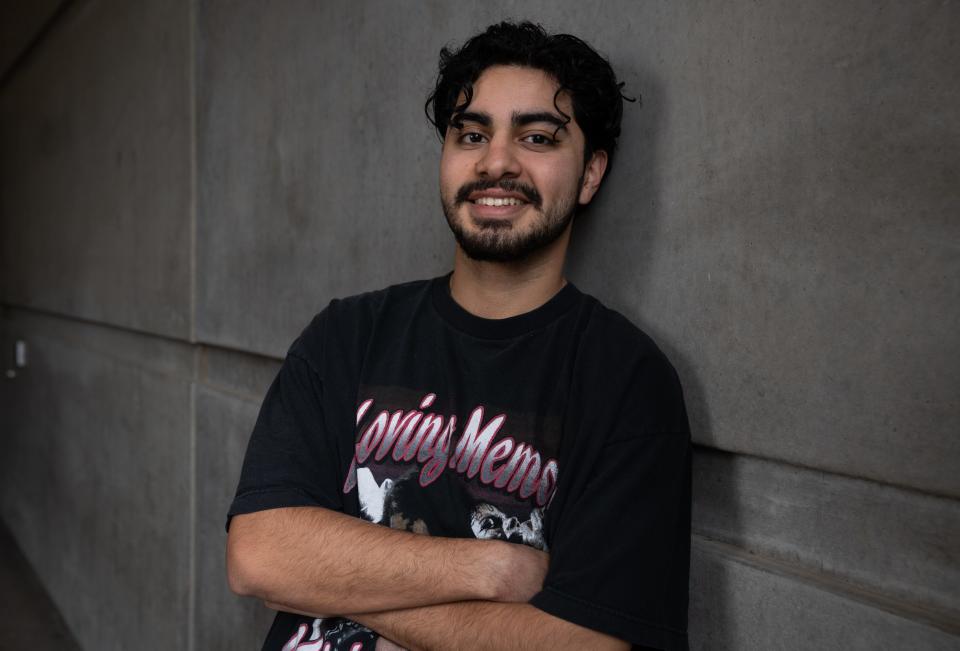

The insults, she said, are especially painful considering her family traces its Mexican roots back 10 generations to when the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the 1500s. The discrimination her grandmother faced is one of the main reasons the 22-year-old graduate student from Phoenix was raised only speaking English.

Mexican Americans like Gomez, who grew up in the U.S. more comfortable speaking English than Spanish, used to be scorned as "pochos," more American than Mexican. But a new phrase has emerged for Latinos who have lost the language of their ancestors: "No Sabo Kids."

The No Sabo Kid phrase is applied not just to Mexican Americans but also generally to Latinos who do not speak Spanish. It was coined from the misconjugation of the Spanish verb "saber," which means "to know" in English.

You don't say "No sabo" to say "I don't know" in Spanish, as one of the hundreds of "No Sabo Kids" videos on TikTok explains. You say, "No se" because "saber" is an irregular verb. Kind of like you wouldn't say "I runned" or "I sleeped" in English. You'd say, "I ran" or "I slept."

So calling someone a No Sabo Kid is making fun of the way they speak Spanish, the video says.

Calling someone a No Sabo Kid may have started as an insult. But the term is being embraced as a badge of pride by a new generation of young Americans to show they are proud to be Latino — even if they don't speak Spanish.

To demonstrate their pride, Latinos who don't speak Spanish can now find hundreds of No Sabo Kids-branded merchandise on Amazon, hoodies on Etsy, and T-shirts on websites such as Hija de tu Madre.

By embracing the No Sabo Kid identifier, young Latinos who grew up as millennials or part of Gen Z have taken an insult and turned it around, said Stella Rouse, a political science professor and director of Arizona State University's Hispanic Research Center. They also have utilized social media and technology to create a movement, Rouse said.

"What I see of that movement is Latino kids showing that we are going to define for us what it means to be Latino, and we are not going to let others put a label on us and say, if you don't speak Spanish you are not Latino enough," Rouse said.

At the same time, the No Sabo Kids movement acknowledges the history of Latinos in the U.S. being forced to speak only English, Rouse said. Taking pride in being a No Sabo Kid allows Latinos also to make the statement that it's not always their fault they don't speak Spanish.

"I think there are multiple messages in there, and they are speaking to multiple audiences," Rouse said.

No Sabo Kids represent a growing demographic at a time when the Latino population in the U.S. is soaring and becoming increasingly diverse. The growth is driven not only by immigration but by swelling numbers of U.S.-born-and-raised Latinos who are technologically savvy and politically connected, Rouse said.

"I would argue this is a political, social and even economic movement," Rouse said. "This is a growing group that has the potential to be very influential."

Politicians need to pay attention to the nuances within the Latino community, especially as the 2024 election year heats up and Latino voters play a growing role in the outcomes in tight races.

Every year, 1.4 million additional Latinos become eligible to vote, according to the Pew Research Center. More than 36 million Latinos are eligible to vote this year, up from 32.3 million four years ago, according to Pew. The increase in Latino voters represents 50% of the total growth in eligible voters during that period, according to Pew.

The No Sabo Kids movement underscores that the Latino population in the U.S. is increasingly heterogeneous with growing numbers of third- and fourth-generation Latinos who predominantly speak English, Rouse said. They are more likely to be politically active and have different policy preferences than their parents or grandparents, Rouse noted.

U.S. Latinos attacked from all sides over speaking Spanish

Latinos in the U.S. are often attacked from both sides when it comes to speaking Spanish, said Anaiis Ballesteros, senior director of communications for ALL in Education, a Phoenix-based nonprofit that advocates for Latino students.

They are shamed for speaking Spanish by non-Latinos and shamed for not speaking Spanish by Latinos. She grew up speaking English and Spanish on the border between Douglas, Arizona, and Agua Prieta, Sonora.

On one hand, Spanish-speaking parents often don't want their children to learn Spanish out of fear they will face discrimination in America, where assimilation and speaking only English has long been the norm, she said.

"Parents don't want their kids to suffer the bullying or shaming of not speaking English or having the (Spanish) accent when they speak English," Ballesteros said. "So they choose not to even teach them their native language."

On the other hand, Latinos who only speak English often are shamed for not speaking Spanish by other Latinos, she said. She believes that the shaming is rooted in concerns among some Latinos that they need to actively hold onto the Spanish language because of ongoing attempts to take it away, she said.

She pointed out the controversy over dual language programs in Arizona. State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Horne has threatened to withhold education funding from schools and gone to court to force monolingual Spanish-speaking students in Arizona to only speak English at school by barring them from participating in dual language programs, where students learn in English and Spanish.

That seems like a double standard, Ballesteros said.

"Then you see all these dual language schools pop up in very affluent areas where there are white families sending their kids to learn Spanish, and they are applauded for doing it," Ballesteros said.

'I remember too': Meet the group resurrecting lost history of Phoenix's bulldozed barrios

'I can't change the way someone views me'

A September 2023 survey by the Pew Research Center found that 85% of Latinos feel it's important for future generations of Latinos to speak Spanish. At the same time, nearly as many Latinos, 78%, said it's not necessary to speak Spanish to be considered Latino, the survey found.

The survey illustrates a tension about the views of Latinos in regard to the Spanish language, said Mark Hugo Lopez, the Pew Research Center's director of race and ethnicity research.

About half of U.S. Latinos said they had felt shamed for not speaking Spanish, the survey found.

One of those is Noah Patch, 20, a third-year business student at ASU.

Patch's mother is Mexican American, and his father is Native American. He grew up speaking mostly English and sometimes got shamed for not speaking Spanish well.

In college, he recalled, he met Latino students speaking Spanish at a friend's apartment. Patch joined in but couldn't follow the whole conversation, so he said, "I didn't catch what you said."

The other students turned and muttered something to each other in Spanish.

"They were clearly saying something directed toward me, but in Spanish, of course. They kind of chuckled and laughed a little bit," Patch said.

The incident left Patch feeling less accepted by the Spanish-fluent Latinos at the party, who were clearly looking down at him, he said.

"They were like, 'He's cool, but he's not truly one of us,'" Patch said.

After that incident, Patch spent a semester studying in Spain, where his Spanish improved. He speaks Spanish every chance he gets and no longer lets people who try to shame him bother him.

"At the end of the day, it is what it is," Patch said. "I can't change the way someone views me, whether I speak Spanish or not."

She found herself through art: Now, this Phoenix poet uses it to strengthen her community

From middle school to college, regularly questioned about Spanish

Gomez, the Phoenix woman whose Mexican roots go back 10 generations, can recall many examples of being shamed for not speaking Spanish.

She attended middle school in Laveen, a predominantly Latino neighborhood of Phoenix. Most of her classmates, she said, were bilingual.

"They would always ask me, 'How do you not know Spanish? Why don't you know Spanish?'" Gomez said. This happened "all the time, like 24/7."

After high school, Gomez tried to join a student club called "Latinos on the Rise" in her first year at Allegheny College in Pennsylvania. She attended one meeting and never went back.

"I felt so embarrassed because most of the meeting they were speaking Spanish," Gomez said.

At the same school, she tried to make a connection with a Mexican American professor, one of the only Latinas teaching outside the Spanish department at Allegheny, which is located in a small town in western Pennsylvania.

The professor tried to speak to Gomez in Spanish, then asked, "Why don't you speak Spanish?" But not in a curious way, Gomez said.

"It was more like demeaning," Gomez said.

Gomez has since embraced being a No Sabo Kid.

The turnaround came during the 2022 general election. A Republican Latina won a congressional seat in a South Texas district that a Democrat had held by winning over Latino voters, who traditionally lean left.

Gomez said she sees a connection between No Sabo Kids like herself and the role Latinos who don't speak Spanish are playing in the evolving Latino political landscape in the U.S. That connection prompted her to pursue a Ph.D. in political science at ASU to study Latino partisanship and voting behavior. She's completing the first year of the doctoral program and plans to become a professor or political consultant after graduation.

"Just because I don't speak Spanish, I shouldn't limit myself and engage in the Latino community," Gomez said.

'A language that really isn't mine'

Evie Reyes-Aguirre, a 48-year Phoenix resident who grew up in Los Angeles, also recalls being shamed by other Latinos for not speaking Spanish growing up.

One incident, when she was six or seven, jumped to mind. During a family trip to El Paso, a woman noticed her black hair and Mexican features and assumed she spoke Spanish. When Reyes-Aguirre responded in English, the woman "gave me the dirtiest look," she said.

"'You should be ashamed of yourself for not speaking Spanish,'" Reyes-Aguirre recalled the woman telling her. "I remember feeling scared. I was a kid, right, and here was this adult chastising me for not speaking Spanish."

Reyes-Aguirre later learned Spanish as an adult in her 20s. While working at the Los Angeles Housing Department, she assisted Spanish-speaking tenants.

But the more she learned about her family's Indigenous roots in Mexico, Reyes-Aguirre said, she realized Latinos shouldn't be shamed for not speaking Spanish or English.

"I started to recognize that Spanish is just another colonial language, just like English," said Reyes-Aguirre, the program coordinator at Tonatierra, a nonprofit that promotes Mexican ties to Indigenous cultures and languages. "It really kind of shifted how I would feel guilty or allow people to shame me for not speaking a language that really isn't mine."

For the past 20 years, Reyes-Aguirre has been learning a third language: Nahuatl, the Indigenous language of the Aztecs.

"No Sabo Kid" in Nahuatl?

"Ahmonicmati."

Reach the reporter at daniel.gonzalez@arizonarepublic.com.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: What is a 'No Sabo Kid' and why politicians should pay attention