NJ residents want transparency in government. That much is clear | Stile

Transparency ― opening a public window on the grinding gears of government and party politics ― is all the rage these days.

The clamor for a more open, democratic process is most evident in the fierce blowback lawmakers are facing over a plan to gut the state’s Open Public Records Act, a crucial yet imperfect tool used by the public and the press to keep tabs on the inner workings of government.

It’s the law that forces the public entities to release government documents, ranging from routine to sensitive and internal. They are the type of documents that officials would prefer to keep under seal. But legislators are in a rush to tighten that seal, sparking an uproar that caught many by surprise.

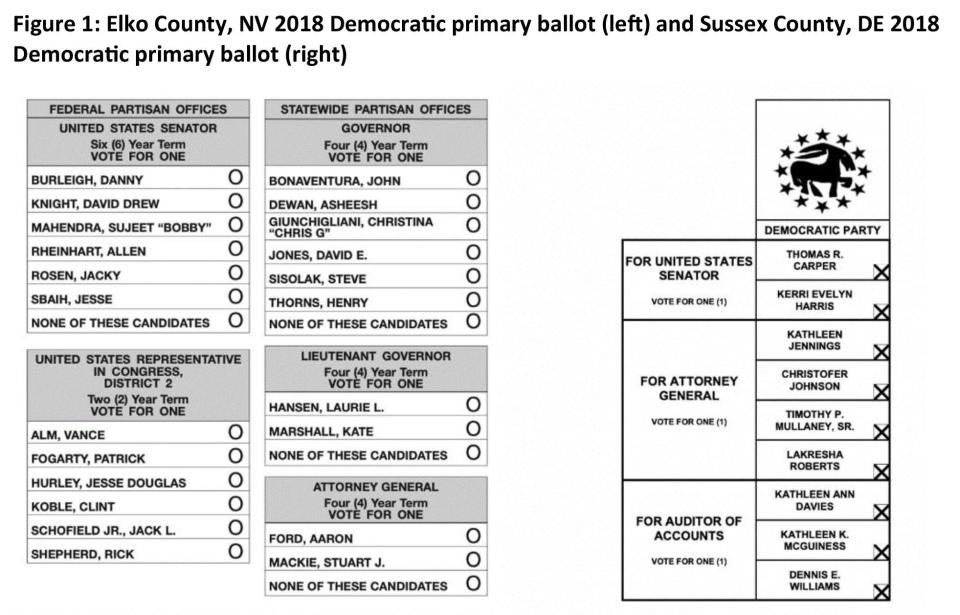

Transparency ― and its role in strengthening democracy ― was also an underlying theme in last week’s historic federal appellate court decision that threw out ― at least for the June 4 Democratic primary ― the antiquated “county line” ballot design. It's a powerful, anti-competitive, anti-democratic tool wielded by county leaders and party bosses for decades.

Winning a spot on the coveted "county line" ― a column where other endorsed candidates are bracketed together ― was almost a guaranteed ticket to victory. Candidates forced to run "off-the-line" usually did so in some obscure, sure-to-lose spot on the ballot. Landing on the line, in many counties, was the purview of party bosses in a closed-door process.

Yet the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals tore the clubhouse door off its hinges. It found that the county line “put the thumb on the scale for preferred candidates, impacting election outcomes before the vote is cast.”

The new ruling requiring a new “block office” ballot style ― where candidates for the same office are grouped together ― could lead to more choices on the ballot. More democracy, more choices and fewer closed-door machinations that led to predictable winners.

There have been other transparency measures that continued a slow crawl through a cautious Legislature. A measure giving civilian boards subpoena power in their oversight of police misconduct flickered for a moment in December before dying in the lame-duck session. And the Legislature never held public hearings on the pandemic-era failures under Gov. Phil Murphy's administration that led to more than 200 deaths at state-run homes for veterans.

Yet the mood is clearly changing. The recent 3rd Circuit decision was a historic breakthrough that not only is shaking up the calcified status quo of New Jersey politics but is sparking hopes that more transparency and more reform are in the offing.

More Stile: Curtis Bashaw — and all NJ Republicans — face a Trump-laden obstacle course

Already, good government advocates and campaign finance watchdogs are dusting off their wish lists of democratic and transparency reforms that were once deemed pie-in-the-sky ideals and dead on arrival in a Legislature steeped in the party machine tradition. It was only a year ago that the Legislature passed the ironically named “Elections Transparency Act,’’ which increased the allowed size and volume of campaign contributions.

More, not less, transparency?

Now some advocates believe the political environment is ripe for a pivot in the opposite direction.

They believe it's time to restart the conversation on limiting campaign money, including reviving the idea of using public tax dollars to underwrite the costs of legislative races, which occurs in six other states, including New York. Implementing such a plan in New Jersey is not as far-fetched as it seems: Public financing has been available for governor’s races since the mid-1970s, and in 2004, the state allowed a limited pilot program in three legislative districts.

Both campaign finance reforms would further weaken the grip of machine power, advocates say, and lead to more competition and openness in the process. Relying on public money rather than pay-to-play contributions would reduce the shell games of big money (but not entirely the secrecy ― outside independent groups and other “dark money” accounts would still seek to leverage their influence).

There are still obstacles on the short-term agenda. For one, a separate federal court case, Conforti v. Hanlon, could have far reaching implications. The case, which may be heard in the fall, could permanently banish the “county line” bracketing for both parties. The 3rd Circuit ruling last week applies only to Democratic contests in the June 4 primary.

Julia Sass Rubin, a Rutgers professor whose analysis of the county line power served as crucial evidence in the most recent federal rulings, believes legislative leaders will try to preempt the Conforti case by passing “reforms” that allow for changes in ballots while preserving their power to select and bracket candidates.

Still, Sass Rubin believes that there is now momentum for a change that, for at least the time being, has weakened the power of the party machines.

“I do think that there is an opening for real reforms," she said. “I’m not naïve. I don't think it's like a switch is going to go off.” Yet she cited the surprising number of legislators who publicly endorsed discarding the old balloting system, and how candidates for governor in 2025 have also gone on record calling for permanently reforming the ballots.

More tests ahead

The spirit of transparency will be tested in other ways in the coming weeks. The OPRA reform, which was pulled last month amid public outcry, is being revised and negotiated by the legislative leaders. A new version of the measure may be introduced before the end of the month.

But a recent Fairleigh Dickinson University poll found that the public is not receptive to any legislative attempts to gut or limit the scope of the 22-year-old law. The poll found that 81% say they would support keeping the system as it is, instead of tightening access, while about 14% were in favor of the changes.

“It’s rare to see any bill attract this much opposition,” Dan Cassino, the director of the poll, said in a statement. “Republicans and Democrats, young and old, Black, Hispanic and white: nobody thinks this is a good idea.”

In other words, the push for openness and transparency isn’t just a parlor game played out in the hallways in the Statehouse between the defenders of the status quo and grassroots advocates. It’s a demand coming from the kitchen tables of voters throughout the state. And it's a loud one.

Charlie Stile is a veteran New Jersey political columnist. For unlimited access to his unique insights into New Jersey’s political power structure and his powerful watchdog work, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: stile@northjersey.com

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: NJ government must embrace transparency. Its residents demand it