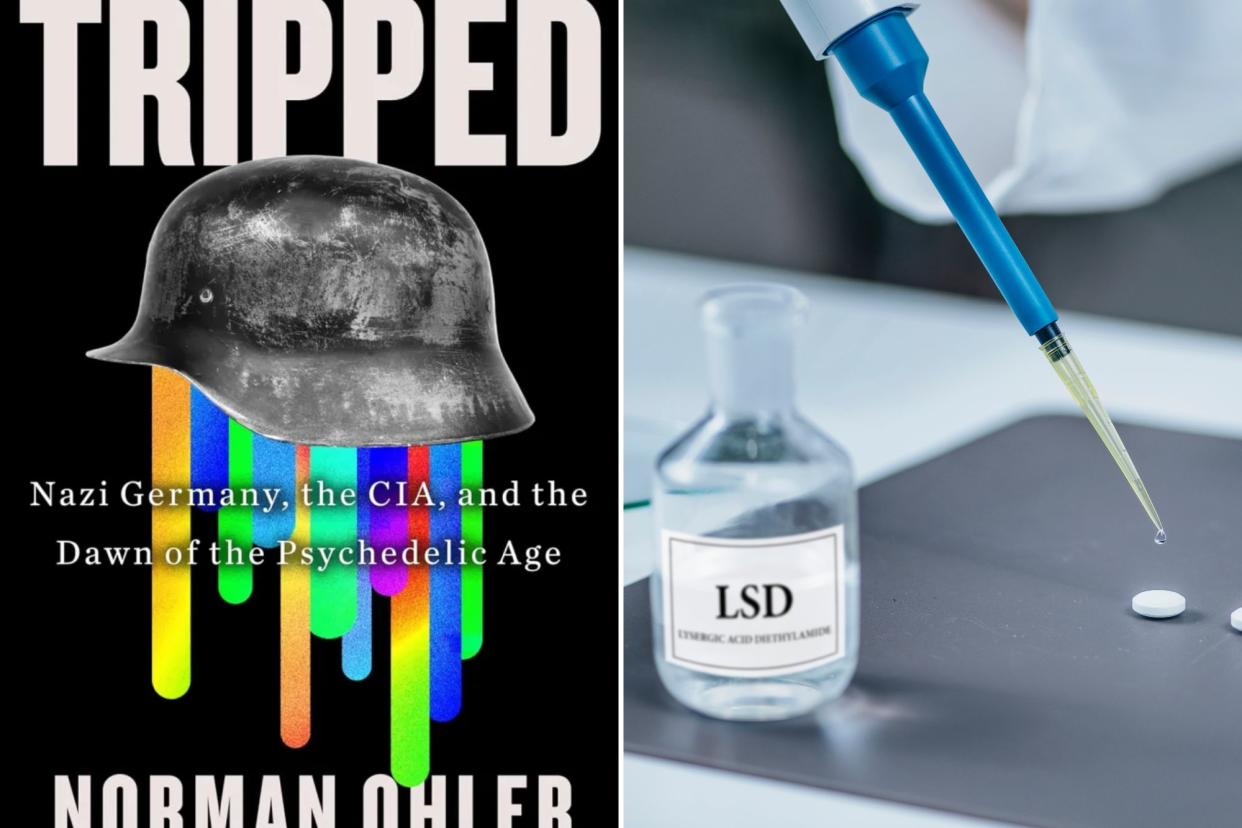

How the Nazis helped ‘discover’ LSD

With LSD finally gaining mainstream acceptance — just last month, the FDA granted breakthrough status to an LSD formula to treat anxiety — author Norman Ohler investigates how it took so long for the drug’s therapeutic benefits to be taken seriously.

His conclusion: Blame the Nazis.

Not only was the US government introduced to LSD through Nazi research, the Third Reich “shaped much of the federal government’s early attitudes around it and other psychedelics,” Ohler writes in “Tripped: Nazi Germany, the CIA, and the Dawn of the Psychedelic Age” (Mariner Books), out now.

When the Nazis “elicited a potential weaponized use for LSD, the drug was never able to shake that taint.”

The Germans had access to LSD as early as 1943, thanks to the close relationship between Nazi biochemist Richard Kuhn, who was developing biochemical weapons for Hitler, and Werner Stoll, a Swiss psychiatrist who conducted the first scientific studies on LSD effects.

But it’s unclear if LSD was part of the experiments at Dachau, where Nazi scientist Kurt Plötner used Jewish prisoners as test subjects in his search for a truth serum.

Dr. Plötner’s notes mysteriously disappeared just before the Nuremberg trials in 1945, likely by agents working for the US military-funded Alsos Mission, who “wanted the subject kept secret,” Ohler writes.

The US military was detemined to, in their words, “exploit German science and technology for the benefit” of America. With the help of Harvard researcher Henry K. Beecher — who realized Nazis likely used LSD because it’s easier than mescaline to dose patients without their knowledge — the top secret MKUltra program was launched in 1953 to investigate if psychedelics could be weaponized just as the Nazis intended.

When they discovered that LSD couldn’t turn people into living puppets, the US government followed the other Nazi protocol when it came to drugs: Strict prohibition. Drug-users in Nazi Gemany were often sent to concentration camps.

“When people think of LSD, they don’t think of the Nazis,” writes Ohler. “And yet that unseen hand played a role in framing our laws.” Time will tell if that Nazi thinking about LSD will become a thing of the past.