Navy Blue: The Admiral's Ferrari 500 Mondial Goes Up for Sale

UPDATE 8/25/2018: Gooding & Company sold this gem for $5,005,000.

Despite the fact that Gioacchino Colombo’s V-12 design is likely the engine most closely associated with Ferrari, powering many of its most notable automobiles during Enzo’s tenure at the company’s helm, Aurelio Lampredi actually designed more engines for the Prancing Horse. When a supercharged version of the 1.5-liter Colombo motor didn’t fare well in Formula 1, Ferrari turned to Lampredi for an alternate, 3.3-liter naturally aspirated take on the V-12 layout, which later found its way into road cars such as the 340 America and, in 5.0-liter form, the 410 Superamerica. But the big twelve didn’t suit every racing formula, or indeed, every circuit, which led the company down other roads, into experimenting with inline-fours, sixes, and even an aborted I-2 design with four-valve heads that produced an impressive 175 horsepower in testing. It was abandoned due to terrible balance, which led to breakage of both test stand and crankshaft.

Outside the twelve, the most successful of Lampredi’s designs for Ferrari was the inline-four, originally designed for Formula 2 competition in 1951. In sports-car racing, the engine debuted in two displacements simultaneously, in the form of the 2.5-liter 625TF and the 2.9-liter 735S. In late 1953, the two-liter 500 Mondial arrived, carrying a de Dion axle out back in place of the V-12 cars’ live unit and weighing in at a scant 1590 pounds. And that’s really where the story of the Admiral’s Ferrari begins.

Bay Farm Island and the End of a Famous International Playboy

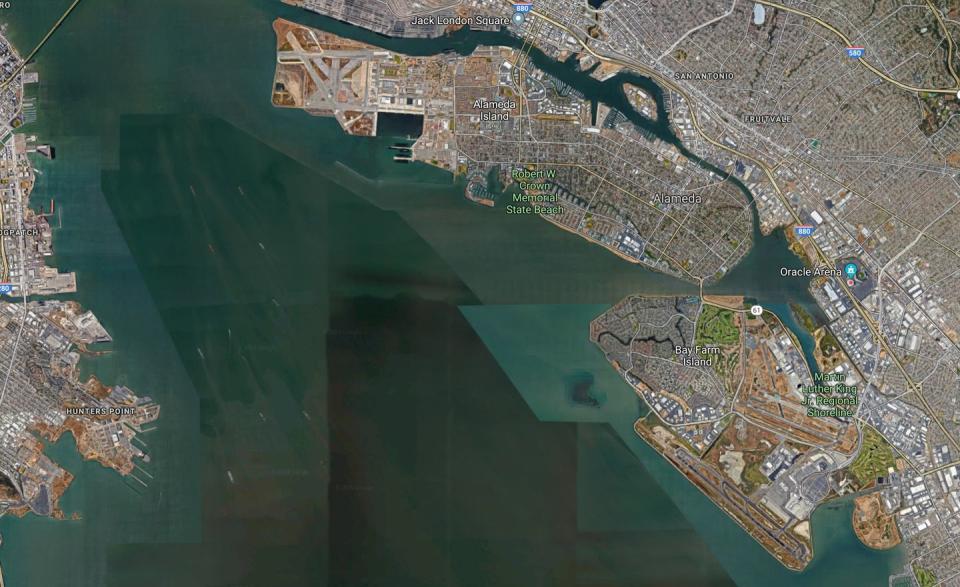

But let’s take a moment and fast-forward to 1960 and a place called Bay Farm Island. It’s an odd little piece of real estate, jutting out into San Francisco Bay south of downtown Oakland. Unlike Alameda Island, just to its north, which started life as a peninsula and was later cleaved from the mainland by the Oakland Estuary, Bay Farm was once an island asparagus plantation whose channel was filled in until it fused with a peninsula connected to the shore. The small, Victorian-dotted city of Alameda straddles both land masses, and during World War II, the town was bookended on the north and south by naval air stations.

To walk up Alameda’s cracked, weed-riddled runway today, 21 years after the base’s closing, is to look across the water at the new eastern span of the Bay Bridge paired with San Francisco’s revised skyline and be reminded that although it was changing even then, the Alameda of 1997 was somehow closer to the Alameda of 1976 than it is to the Alameda of 2018. For Northern Californians of a certain age, Naval Air Station Alameda still stands as an indelible part of the psycho-geography of a NorCal that was and no longer is. It was the spot where, in 1942, the Doolittle Raiders loaded their B-25 Mitchell medium bombers onto the USS Hornet, en route to lob the first bombs at Tokyo, not six months after Pearl Harbor. During the Cold War, Alameda was home to the “nuclear wessels” so anxiously sought by Pavel Chekhov in 1988’s Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home.

Down on the former peninsula integrated with Bay Farm Island, attempt to walk on the former NAS Oakland’s runway and you’re liable to find yourself in the path of a fast-moving Southwest 737. After the war, the naval installation gradually turned more and more of itself over to civilian operation, resulting in what is today’s Oakland International Airport. In 1960, a year before the navy pulled out of the facility entirely, it’s where a young officer named Robert Phillips found himself stationed. His office, he notes, was “roughly where the Oakland rental-car center is now.”

In this day and age, it’s hard to imagine a Lieutenant Junior Grade buying even the most frazzled Ferrari, much less a five-year-old racing machine with a global competition pedigree, but in May 1960, Phillips heard that there was a Ferrari sitting at a Rambler dealership in Richmond-a quick shot up the new Nimitz and Eastshore freeways from NAS Oakland-and he thought he’d go have a look. The Italian sports-racer had been left there by a traveling salesman and USAC driver Robert Ready Davis, who had been transferred to the Bay Area and hauled the car out from Indiana with him. Davis had seized the rear axle at Road America the year before, and hadn’t found the wherewithal to fix the Ferrari’s myriad problems.

Prior to Ready’s ownership, the car had been raced by former fighter pilot Raymond Hassan of Cincinnati. Hassan had purchased the Mondial from Dominican diplomat Porfirio Rubirosa, who had won with the car at Nassau and then entered it in the 1956 12 Hours of Sebring. Wily, middle-aged Juan Manuel Fangio and young, gifted Eugenio Castellotti-a blinding combination of talent in one car if ever there was one-won that race in an 860 Monza, a big brother to the Mondial, featuring a Lampredi four punched out to a whopping 3.4 liters. It was the first time a Sebring race covered over 1000 miles and the first time a manufacturer swept the top two positions on the grueling enduro’s podium. Luigi Musso and American second-generation racer Harry Schell earned that second spot in another 860. Of the four men responsible for the Ferrari factory’s one-two punch of a debut at Sebring, Fangio was the only one who would live to see 1961. Rubirosa and his co-driver, Jim Pauley, won the historic race’s two-liter class in the Mondial, finishing 10th overall.

Rubirosa was one of those fantastical characters who one presumes only exist in fiction. A trusted consigliere of Dominican strongman Rafael Trujillo-as well as his former son-in-law-“Rubi” excelled at polo, raced cars, and was romantically linked to an eye-popping succession of women, including Rita Hayworth, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Eva Perón, Eartha Kitt, and Marilyn Monroe. He received a B-25 plane as part of his divorce settlement from tobacco heiress Doris Duke and a second B-25 as part of his divorce settlement from Woolworth heiress (and mother of racing driver Lance Reventlow) Barbara Hutton. His famously generous manly endowment led Parisian waiters to refer to their large pepper mills as Rubirosas. He was also rumored to be an assassin. After Trujillo’s fall in 1961, Rubirosa was stripped of his diplomatic status and found himself questioned, but never charged, by American authorities in the disappearance of a pair of Trujillo’s opponents. He continued on with his outlandish ways until 1965, when he crashed a 12-cylinder Ferrari into a tree after an all-night post-polo-match celebration in Paris. Porfirio Rubirosa was 56 years old.

French Racing Blue? Picard Made It So

Prior to Rubirosa’s ownership, the four-cylinder Ferrari had been under the direct control of the Scuderia-notable because the car wore French Racing Blue livery. Its original owner, Frenchman François Picard, had ordered it that way. Picard raced his new Series II Mondial in the 1955 Grand Prix de 24 Heures de Paris, and then passed it to Gino Munaron, who briefly ran the car in Italian competition before selling it back to Ferrari.

Il Commendatore, a man unafraid to take a gifted penny when one was offered, was plied with the prospect of free transport for his cars across the Atlantic to the first running of the Grand Prix of Venezuela. The offer came courtesy of the profligate, dictatorial Marcos Pérez Jiménez government, which had seized power in a coup seven years before and were, unbeknownst to themselves, ruling on borrowed time. Pérez Jiménez would be deposed by the military in less than three years. In the interim, however, the president and his cronies would continue racking up sizable debts, setting Venezuela up for a very rough time in the 1960s.

Since the blue Mondial Series II was just sitting there doing nothing and seemed well suited to the competition at hand, Enzo decided to bring it along as a works entry, even though the small-displacement Mondials were generally reserved for sales to privateers. Compared to the Series I car that had bowed at the end of 1953, the Series II 500 Mondial featured a stronger (oval tube) frame, an improved front suspension, a new five-speed nonsynchromesh transaxle, a bigger fuel tank, and a revised version of the Lampredi four-banger based on the unit from 1954’s successful 553 F1 car. Nine Ferraris were entered in the Venezuelan race: six clienti cars and three works entries. Picard’s former car was initially driven by Harry Schell, but after Castellotti’s more powerful 857 chunked its drivetrain, Schell was pulled from the Mondial and replaced by the Italian prodigy, who went on to place first in class and fifth overall. It remains the only time the Scuderia has directly campaigned a car painted anything other than red.

A Young Man Buys Himself a Ferrari

Back in 1960 Richmond, Lt. Phillips was having a hard time finding anything resembling the Ferrari he’d heard rumor of at the Rambler dealership. He did, however, find a hulk up on jack stands. It took wiping the muck from the two-liter four’s cam cover for him to ID the partially disassembled contraption. When he saw the famous logo, he knew he had to rescue the broken-down thoroughbred. Phillips negotiated a purchase price of $2225 ($18,833 in today’s dollars, and two-thirds of the lieutenant’s yearly salary) and hauled the wounded racer the 25 miles or so south to Oakland, where he talked the manager of the Naval Air Station’s auto shop into giving him space to store and work on the car. It took the officer nine months of his spare time to return the Ferrari to working order, learning auto mechanics as he went.

When he was finished, Phillips drove the car across the bay and up to the old Cotati Raceway, south of Santa Rosa, to qualify for his SCCA Novice driver’s permit. His first race saw the little Mondial travel over the rolling Coast Range, across the bright, flat Central Valley, following the course of the south fork of the American River on up into the red, green, and gold foothills of the Sierra Nevada for the Georgetown Hill Climb, where it broke the previous year’s course record. Between 1960 and ’61, the competition had become considerably quicker, as Phillips’s valiant rookie effort was only good for 10th place, although it did net him first in Class E. He raced the car at the SCCA event in Stockton a few weeks later, where he placed third in Class E and eighth overall. Then the Navy sent him off to Turkey.

Upon his return stateside in 1964, Uncle Sam assigned Phillips to the Naval Supply Center in Bayonne, New Jersey. The Mondial, meanwhile, sat in storage on the other side of the country. So Phillips went out to California and drove the open Ferrari racer to the East Coast, enduring a New Mexico snowstorm while crossing the Continental Divide. It can’t have been much more comfortable than doing the same thing on a motorcycle or a mountain lion.

In 1988, shortly after Enzo Ferrari’s death, Phillips retired from the Navy as a rear admiral. Nearly two decades ago, he embarked on an eight-year conservation-oriented restoration project with noted Ferrari specialist David Carte, which saw the Scaglietti bodywork stripped to bare metal and repainted in its original French Racing Blue. In early 2008, as the car neared completion, a friend nominated the Mondial for inclusion in that year’s Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance. The selection committee responded enthusiastically to the suggestion, and suddenly, Phillips found himself having to finish the restoration by August. The old warhorse won first in its class and was selected by no less than Jean Todt and Piero Ferrari for the Enzo Ferrari Trophy, a prize in recognition of the best Ferrari on the field.

Some Cars Should Never Be Parked

A few years back, Petrolicious shot a video featuring the admiral’s 500 Mondial roaring through the hills of Monterey County. In it, Phillips is philosophical about his ownership of the Ferrari, aware that he has merely been a steward of the machine for these past decades. And now his time with the car is coming to an end. A decade after its win at Pebble Beach and 58 years after a young man discovered it languishing in at a Rambler dealership 125 miles up the coast from the storied golf links, the 1955 Series II Mondial goes up for sale at Gooding and Company’s annual Pebble Beach auction. In the Petrolicious clip, Admiral Phillips worries aloud that its next owner may consign it to life as a museum piece.

It seems as if this particular automobile couldn’t suffer a worse fate than a quiet retirement locked away as a static bauble. In fact, the mere thought of doing so seems a lot like a gross insult to everybody involved in the car’s history. Do you wanna be the guy to kick sand in the face of a rear admiral of the United States Navy, an international playboy / rumored assassin, and famed Italian engineer Aurelio Lampredi? We think, well-heeled chum, that you do not. As long as there’s gasoline enough to fuel it, this Ferrari should, nay, must be driven. After all, Old Man Lampredi didn’t design that motor not to run.

('You Might Also Like',)

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos