N.B. schools should do more to recognize World Autism Awareness Month, say parents

Shediac mom Stephanie Morris has always been thankful for autism awareness.

She said it's given her son's classmates a chance to ask questions and learn more about him and his uniqueness, and understanding Casey better has led to more acceptance by his peers.

Morris was often included in the educational events surrounding Autism Awareness Month — which is recognized internationally in April, but officially by Canada in October, although Canada does mark Autism Day on April 2 with the rest of the world — and enjoyed speaking openly about Casey and autism.

"I've seen the difference. The children show a lot more understanding and compassion," said Morris.

"If my son is playing on the playground and he's stimming or playing in a way that's a little bit different from the other children, the kids wouldn't stop and stare. They wouldn't be taken aback by him. So I saw the impact that keeping that conversation going each year … had on the kids."

But that was all back home in Newfoundland.

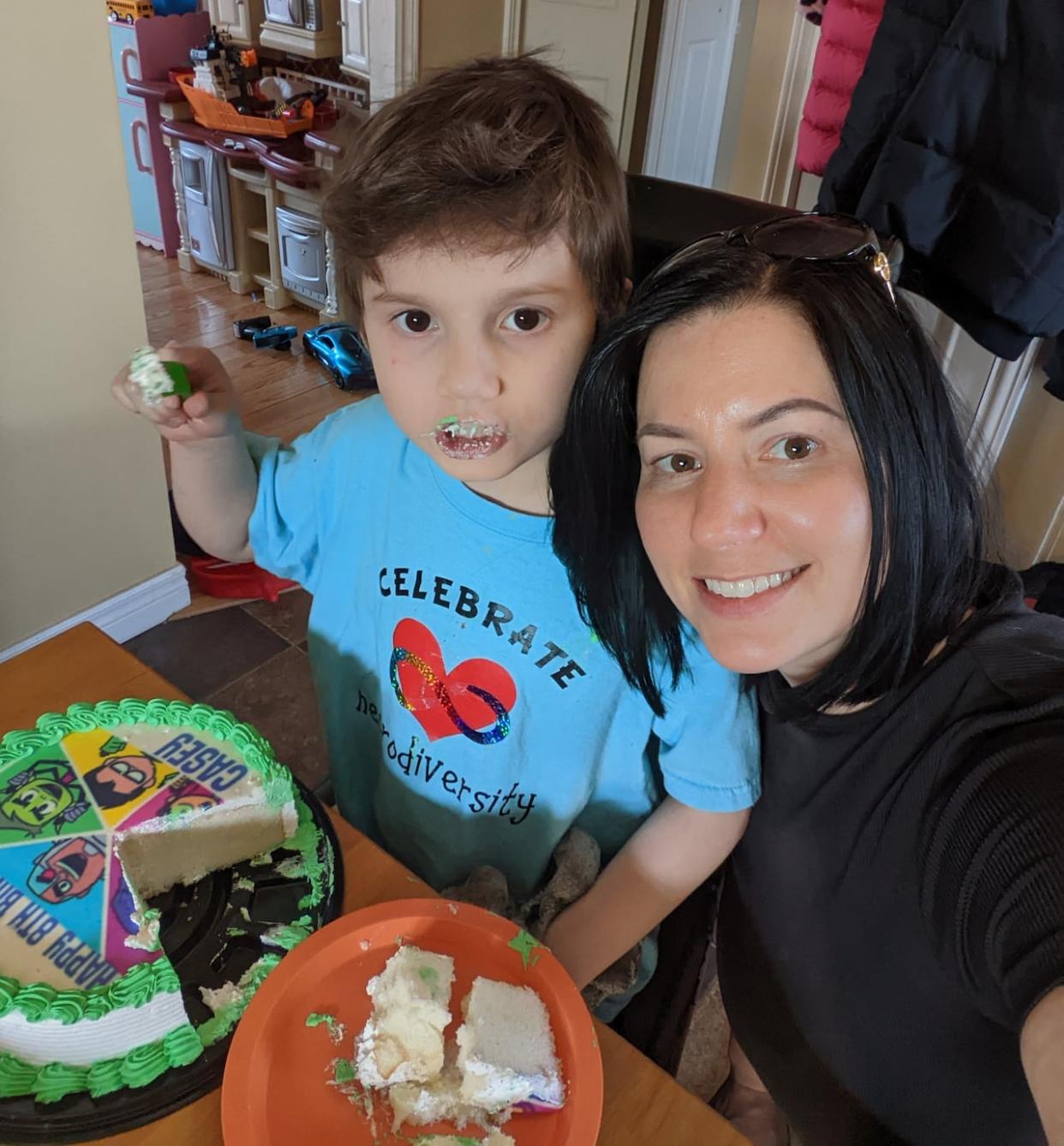

Stephanie Morris with her children, nine-year-old Casey and six-year-old Nolah. (Submitted by Stephanie Morris)

When she moved to Shediac in December, she was surprised not to see anything on the school calendar related to autism awareness in April.

When she contacted her daughter's teacher — she now homeschools Casey — Morris said the teacher was receptive to passing along books and videos that she had sent along.

The principal, however, was not "overly receptive," said Morris.

"I found the principle of my daughter's school seemed quite dismissive of it, which was surprising to me. I thought it would be something that they'd be very receptive to — taking an opportunity to teach children about neurological diversities."

She also sent an email to the Anglophone East School District and is still waiting to hear back.

"I'm not really sure what more I can do to advocate for it," said Morris. "I can't see why you wouldn't take an opportunity to educate the youth and keep that conversation going and take that opportunity to teach our youth to be more tolerant, accepting people."

Schools decide approach

When contacted on Monday, Shediac Cape School principal Catherine Lloyd referred inquires to the district.

In an emailed response to CBC, Stephanie Patterson, director of communications for Anglophone East School District, said the district acknowledges and celebrates "all forms of diversity."

She said the "goal is not only to acknowledge different awareness months but to ensure that exclusivity and support are embedded in the daily life of our schools."

But she didn't answer questions about whether the district provides any guidance or resources to schools about recognizing awareness dates.

A school's artwork to recognize World Autism Awareness Day on April 2. (Submitted by Autism Canada)

Department of Education spokesperson Diana Chávez said individual schools are responsible for deciding how to commemorate all types of awareness days, weeks and months.

Morris recently voiced her concerns about a lack of recognition for autism awareness to the 1,600-member Autism Support Group New Brunswick's Facebook group. She said the "overwhelming majority" of parents who responded said they faced a similar situation — "schools just don't seem to be acknowledging this at all, which was just very surprising to me."

She said the group had the same experience with World Autism Awareness Month in April, Autism Awareness Day on April 2, and in October when Canada recognizes autism awareness.

The Public Health Agency of Canada was asked last week why Canada doesn't celebrate autism awareness in the same month as the rest of the world. In an emailed response sent Monday afternoon, an official said, "The Senate of Canada marked Autism Awareness Month in October 2017, following the 10th Anniversary of the Senate Report Pay Now or Pay Later: Autism Families in Crisis."

To mark autism awareness month last October, federal Health Minister Mark Holland said, "It is estimated that 1 in 50 children and youth aged 1 to 17 have been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder in Canada."

'Opens the conversation'

Lorri Meunier is also a big fan of being open about autism.

For many years, she, too, visited her son Evan's classroom — and others whenever asked — to talk about autism.

She believes that openness and education fostered a better understanding among Evan's classmates and led to him having "a better experience" in school. She thinks it's likely the reason they never had any issues with him being bullied.

Given the positive experience she and Evan had, "I would hope that schools would be open to it," said Meunier.

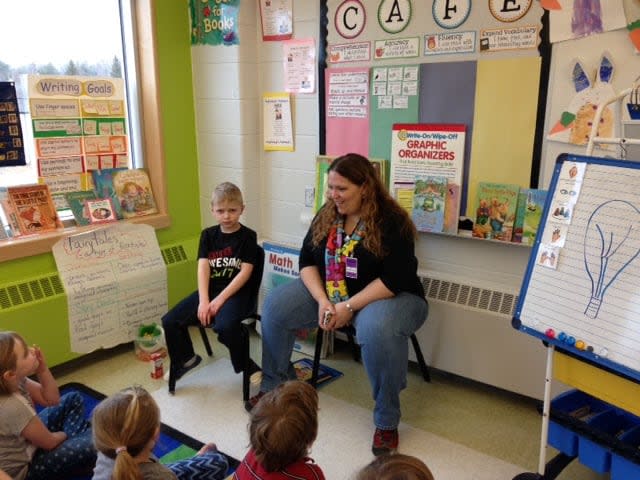

Before the pandemic, Lorri and Evan Meunier often talked to his classmates about autism, including in this photo when Evan was in Grade 2. (Submitted by Lorri Meunier)

She said having open discussions in the classroom gives students a chance to ask questions they may be too shy to ask otherwise.

"I like to think that it opens up the conversation and it lets the kids — or lets anyone — feel comfortable to ask questions," said Meunier.

She remembers being in school and too reluctant to ask questions.

"No one talked about it," said Meunier, which led to misconceptions about the students who may have had invisible differences.

Morris said "it's important to keep the conversation going about the mistakes we've made in the past that have harmed autistics and how we can continue to do better in the future."

She said therapy in the past "focused on suppressing the behaviours that made them appear too autistic, it focused on conforming autistics to the world around them."

Morris said it's important to allow them to interact with the world in a way that's "natural for them — without facing criticism for doing so."

"There's nothing wrong with a child spinning in place, jumping in place, flapping hands or making a repetitive noise because they are excited at the playground — this is their normal and that should be celebrated."

Understanding leads to acceptance

The executive director of Autism Canada said it's important for schools to be open about autism and take an active part in educating students.

Some, said Jamie McCleary, do a better job than others. She said there's even a difference between how her two sons' schools approach autism awareness in New Tecumseth, Ont., about 100 kilometres northwest of Toronto.

McCleary said understanding breeds acceptance.

For example, understanding why autistic students exhibit overt behaviours will help students understand and accept them.

Jamie McCleary is executive director of Autism Canada. (Submitted by Jamie McCleary)

Sometimes, said McCleary, life is more difficult for autistic children who exhibit more overt behaviour because it's clear they're autistic.

"It's a lot more isolating for the children who have very subtle autistic behaviours."

Autism awareness days can provide the opportunity for students to explain their autism and describe how it manifests itself uniquely in them.

McCleary said it's "really empowering for children because they can stand up and say, 'I'm not weird, I'm not quirky, I am autistic. This is why I do these things.'"

She said being able to explain those things helps autistic students "feel more included and to not feel quite so isolated because they're different or that those differences can be explained."