Mother's boxes held letters home from U.S. Navy seaman on cusp of World War II

When my parents died and our childhood home was sold, my siblings and I faced the task of packing up years of their memories. My father’s medical office also had to be emptied and several of the boxes from there and the house ended up in my garage.

Meanwhile, life flew by and those boxes remained unopened for years. Recently, in an effort to declutter so my children won’t have to go through (and throw away), I started sorting through those mountains of boxes and stumbled upon plenty of treasures. I found childhood letters my father wrote to his parents, medical school notebooks complete with his sketches of various anatomical conditions, and clippings of newspaper articles I have written though the years, among other sentimental items.

Mama’s boxes contained her 1937 Armstrong Junior College diploma, get well cards that she received when she had her appendix removed while she was at the University of Georgia, and correspondence from friends. Mind you, these were letter-writing years when people sat down and wrote long letters to friends and loved ones.

A trove of letters to mom

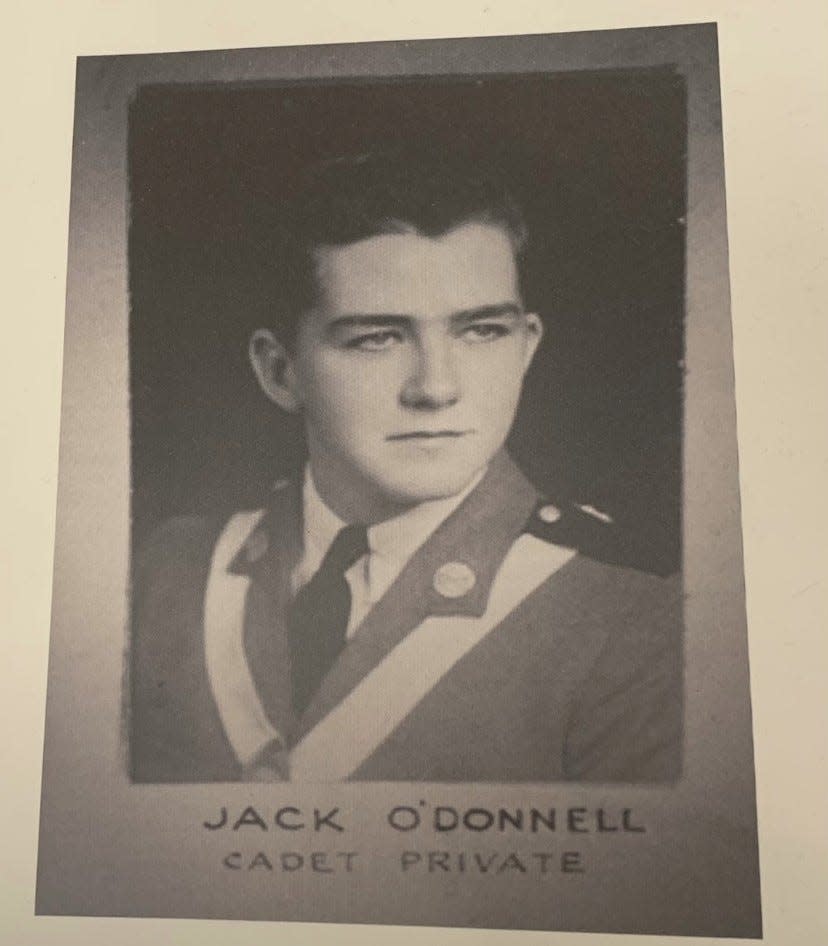

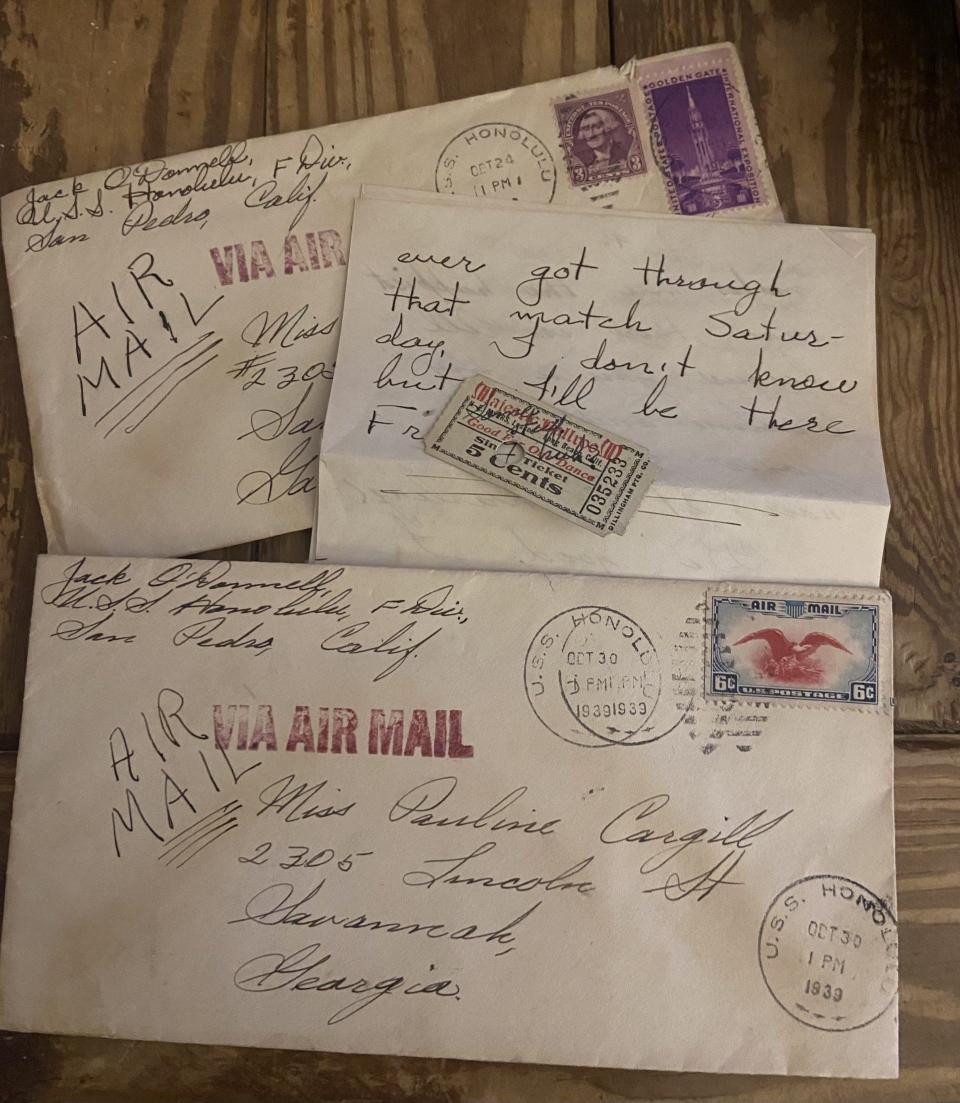

A half dozen of those letters were written to Mama in ’39 and ‘40 after she graduated from UGA. They were from fellow Savannahian Jack O’Donnell, a Benedictine Military School graduate who enlisted in the U.S. Navy in May ’37 at the tender age of 18.

The letters from Jack that I found likely weren’t the only ones he sent to my mother, but I’m befuddled about what became of the others. Maybe one day I will come across another stack and learn more about Mama’s pal who shared with her snippets of his life in the U.S. Navy aboard the USS Honolulu during the years before America entered the war.

Jack wrote in cursive that he may have learned from Catholic nuns. But who knows?

Many years ago – perhaps it was around Memorial Day – I remember my mother casually mentioning to me that a friend of hers was killed during WWII. I didn’t pry but now I wish I had asked her more questions. How did they meet and why they stopped writing each other.

Mama’s friend Jack was one of approximately 500 Savannahians who lost their lives during WWII. Every year on Memorial Day we remember those men and women who gave their lives in the service of their country during that war and others.

Jack O’Donnell was a boy, really, like so many other young men who enlisted in the service at a young age. Because he was only 18, he had to have his father’s permission to join the Navy.

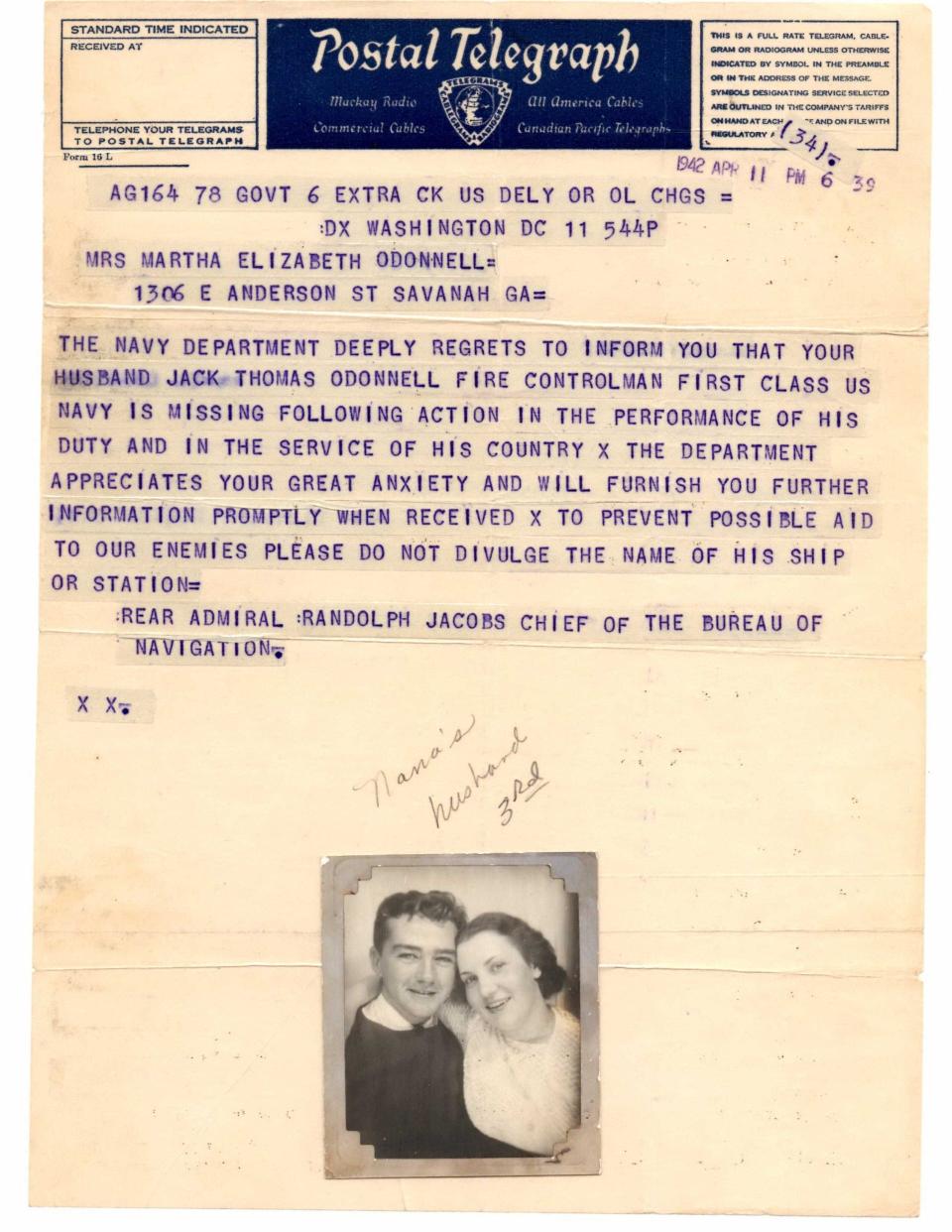

And like many other military men, after five years in the Navy (with two of those during the war) he first was believed to be missing in action. On Feb. 19, 1942, he was aboard the USS Peary in the Darwin, Australia, harbor when it was bombed by the Japanese. Jack was among 80 men who were killed during the air raid, but his body was never recovered. His name and those of the other men who died are on a plaque at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in the Philippines.

Letters home from war

I was intrigued by this young man who, in his letters to Mama, seemed thoughtful, funny and at times, wise beyond his years – a character trait shared by so many men of that era. I think Mama would understand that I’m not trying to invade her privacy by sharing parts of those letters she packed away. I think she would be glad that people will know a little bit more about her young friend, Jack.

Consider this passage from one of his letters: “It’s one of those quiet Sunday afternoons when everyone is glad just to be alive.”

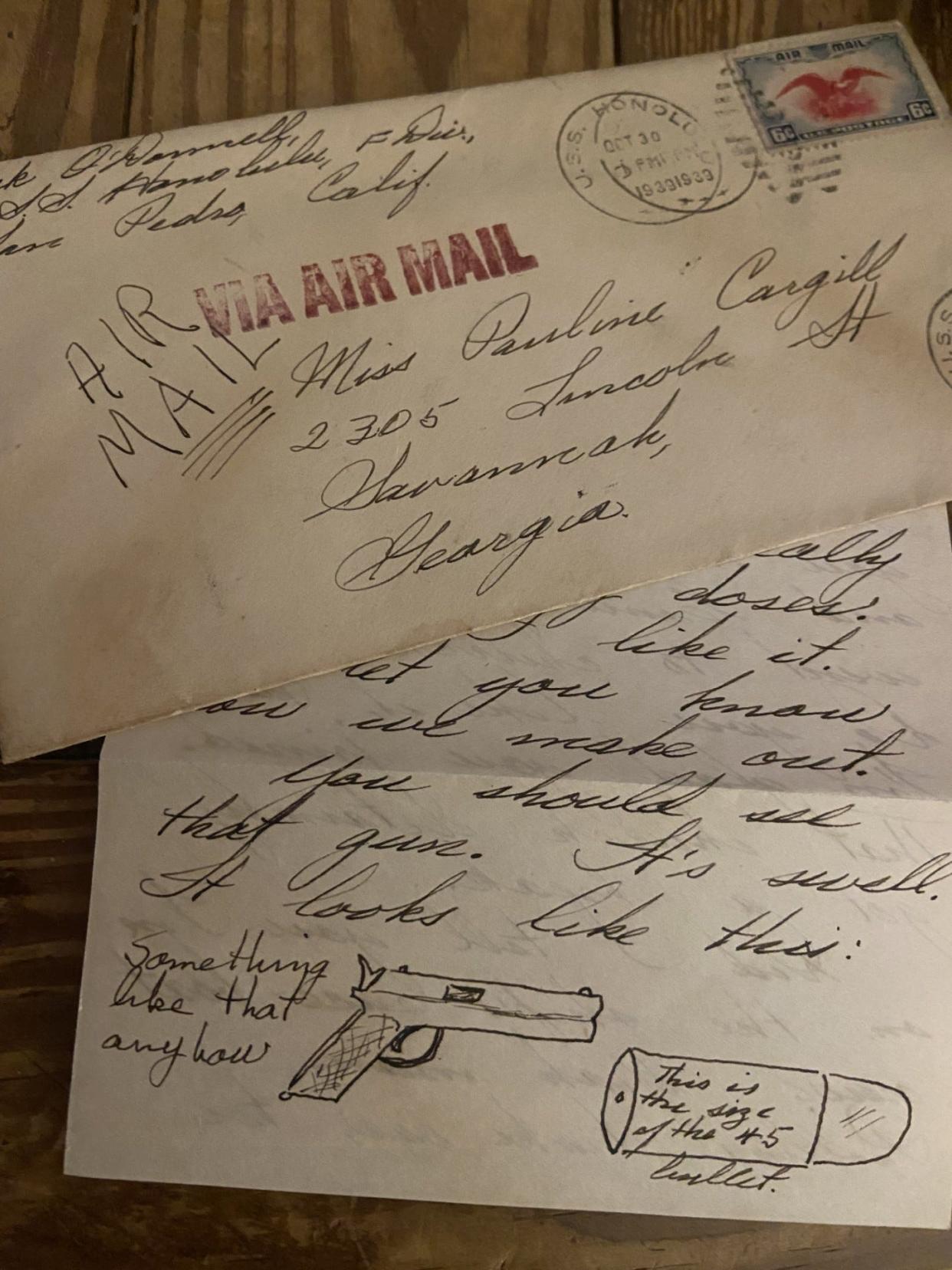

And this: “Yesterday was Navy Day and the Navy held a fleet pistol match. Some guy off the Honolulu by the name of O’Donnell won it! You should see the pistol the Navy gave me as a prize. Gee, it’s swell. I feel so good about winning the contest. They’ve got my gun on the bulkhead in the ship’s armory where all hands can see it. I’m so proud. Oh golly!”

Sometimes he sounded homesick: “It will be good to come home again, knowing that I’m coming home and hearing those train wheels click and finally hearing the conductor say, ‘Savannah – all out for Savannah’ and jumping down from the car onto the platform.”

In one letter, Jack talked about how he spent his $60 a month salary:

$20 (maybe $25) home;

$15 clothes;

$12 living expenses;

$5 savings for Christmas.

In a Jan. 1, 1940 letter Jack sounded philosophical: “This seems to be the proper time to look back at old 1939 and wonder just how much good we did – how much we did to make other people enjoy life. I think the resolution that seemed the most unselfish and the most thoughtful to me was made by Mrs. Davenport. She said, ‘My only resolution is to do everything I can to make my family a little happier that they were last year.’ That’s a mighty fine thing to resolve.”

In the same letter he also revealed a healthy sense of humor: “People over here (in California) don’t celebrate the way we do. Gosh, they all get looped up like a bunch of dopes. At least people in Savannah know how to drink.”

To find out more about Jack, I tried to think of anybody and everybody I could contact who might have heard of him – an ordinary Savannah boy who yearned to serve his country. I had little luck but did discover that he was born in Savannah on Feb. 26, 1919, and was baptized on March 16 of that year at what is now the The Cathedral Basilica of St. John the Baptist. His parents were Thomas Francis “Frank” O’Donnell Jr. and Mary “Mamie” Sheehan O’Donnell. He probably was named for his maternal grandfather, John Thomas Sheehan who came to Savannah from Ireland in the late 1800s. His godparents were his aunt and uncle on his mother’s side, Julia and John J. Foran.

Sadly, the O’Donnell’s first child – named for Frank – was born in 1916 but only lived a year. Jack had no other siblings.

When Jack was a child ― per Savannah City Directories ― the O’Donnells lived at a couple of different locations downtown with family. Frank was an auto mechanic and later a car salesman. By 1934, when Jack was 14, the O’Donnells were divorced. Frank moved into the YMCA downtown on Madison Square, and Mamie and Jack moved in with her mother on Anderson Street.

I learned a little more about Jack by turning to the internet’s Find-A-Grave site, which includes several paragraphs about Jack and his Naval service:

“During the first half of 1940, the USS Honolulu continued operations out of Long Beach, CA. On 08 May 1940, FC3 O'Donnell extended his enlistment for two additional years of service. Later that day, O'Donnell transferred to the Primary Fire Controlman School in Washington, D.C. … he began the 20-plus week school on 13 May 1940. While still in school, FC3 O'Donnell advanced in rate to Fire Controlman Second Class (FC2) on 16 Nov 1940. About a week later on 22 Nov 1940, FC2 O'Donnell transferred to the Receiving Ship (RS) in San Diego for further transfer back to Honolulu …On 05 May 1941, O'Donnell was honorably discharged at the end of his enlistment. Records indicate he extended his enlistment on 08 May 1940 for two years probably as a requirement to attend the FC Primary School. That enlistment should have ended on 09 May 1942. However, on 06 May 1941, O'Donnell reenlisted for four more years of service in Pearl Harbor. It is believed that O'Donnell went on leave in late Jun 1941 possibly to marry Miss Martha Elizabeth, whose surname is not known.”“… on 17 Jan 1942 … O'Donnell was assigned to duty on board the destroyer, USS John D. Ford (DD-228). O'Donnell transferred to USS Peary (DD-226) for further transfer to Ford on the 17th. However, O'Donnell did not transfer to Ford, but remained on Peary for duty. Whoever made the decision to retain O'Donnell on board Peary ultimately cost him his life. USS John D. Ford survived the war.”

Jack’s young bride ― they likely were married a little more than six months ― was living with Mrs. O’Donnell in Savannah when she received a letter dated March 17, 1943, from the Secretary of the Navy telling her that Jack was presumed dead.

Later, a telegram was delivered from President Franklin D. Roosevelt: “In grateful memory of Jack Thomas O'Donnell, who died in the service of his country at Darwin, Australia … He stands in the unbroken line of patriots who have dared to die that freedom might live and grow and increase its blessings. Freedom lives, and through it, he lives -- in a way that humbles the undertakings of most men.”A photograph of Jack with his wife along with the telegram is included in the Find-A-Grave narrative. His widow remarried in the late ‘40s and moved to Washington state. Her granddaughter found the photo and telegram in her belongings after her death and posted them on Find-A-Grave. She told me that she had no idea that her grandmother had been married before.

Jack’s mother remarried in ‘51, less than a month after Frank O’Donnell died at age 56. Shortly after her second marriage, Mamie O’Donnell Dawicek moved to Florida where she lived until her death at 66 in ‘63. She is buried with her parents in Savannah’s Catholic Cemetery. Frank O’Donnell is buried with his infant son and parents at Bonaventure Cemetery.

Polly Powers Stramm is a regular contributor to and former columnist with the Savannah Morning News. Share story ideas with her at pollparrot@aol.com.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Letters home from war take on special meaning on Memorial Day