Most quasars are a ferocious force of nature, but not this one

One of the closest quasars to our Milky Way galaxy is behaving in a surprisingly timid fashion when it comes to affecting its surroundings, new observations with the Chandra X-ray Observatory have shown.

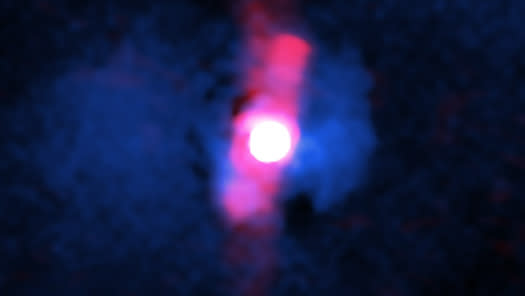

A quasar is the bright central region of a galaxy that hosts a highly active supermassive black hole that is consuming large quantities of gas. This gas, while swirling around the black hole, forms an accretion disk that grows hot and luminous. At the same time, magnetic fields within the disk whip up some of that material, shooting it away in twin jets that race at almost the speed of light. The combination of the disk and the jets, when pointed at us, make quasars the brightest objects in the universe, shining especially brightly in X-rays. The particular quasar observed by Chandra, cataloged as H1821+643, is located in a galaxy 3.4 billion light years away.

In most cases, all that high-energy radiation spouted out by a quasar's jets and disk can wreak havoc in the quasar's surrounding host galaxy. In the form of negative feedback, energy coming from the quasar can heat the surrounding gas and blow it away, preventing it from forming stars or falling onto the black hole. Then, with its primary source of fuel cut off, the black hole stops growing and the quasar starts to vanish.

Related: The Chandra X-ray spacecraft may soon go dark, threatening a great deal of astronomy

Yet, that;s not what's happening to H1821+643, according to Helen Russell of the University of Nottingham, who led the Chandra X-ray observations of H1821+643.

"We have found that the quasar in our study appears to have relinquished much of the control imposed by more slowly growing black holes," said Russell in a statement. "The black hole's appetite is not matched by its influence."

Chandra found that the gas near H1821+643's black hole, which holds about four billion solar masses (an order of magnitude more massive than Sagittarius A*, which is the black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy) is denser and has a lower temperature than gas farther afield. This implies that the quasar isn't pumping much energy into the inner 30,000 light-years of its host galaxy, where this denser and cooler gas can be found.

"The giant black hole is generating a lot less heat than most others in the center of galaxies," said co-author Lucy Clews of the U.K.'s Open University in the statement. "This allows the hot gas to rapidly cool down and form new stars, and also act as a fuel source for the black hole."

Indeed, the black hole is guzzling on 40 solar masses of material each year, while 120 solar masses of hydrogen gas gets annually converted into newborn stars around the quasar. The gas is cooling below X-ray temperatures, at a rate of 3,000 solar masses per year.

Related Stories:

— Why astronomers are worried about 2 major telescopes right now

— X-ray telescope catches 'spider pulsars' devouring stars like cosmic black widows (image)

The quasar's deft touch on its surrounding galaxy is unlikely to last. As more and more material flows down into the accretion disk, its jets will strengthen, eventually reaching the point where the quasar can't help but heat the surrounding gas. Molecular gas needs to be cold, less than 10 degrees above absolute zero, to be able to gravitationally collapse and condense to form stars. Heating that gas will shut down star formation in H1821+643's host galaxy, and the jets will then proceed to blow the hot gas away, perhaps out of the galaxy entirely. This will starve the black hole and result in the quasar eventually switching off.

The findings were published on Jan. 27 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.