There’s more to ask about Bishop Miege president than a long-ago abuse allegation | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

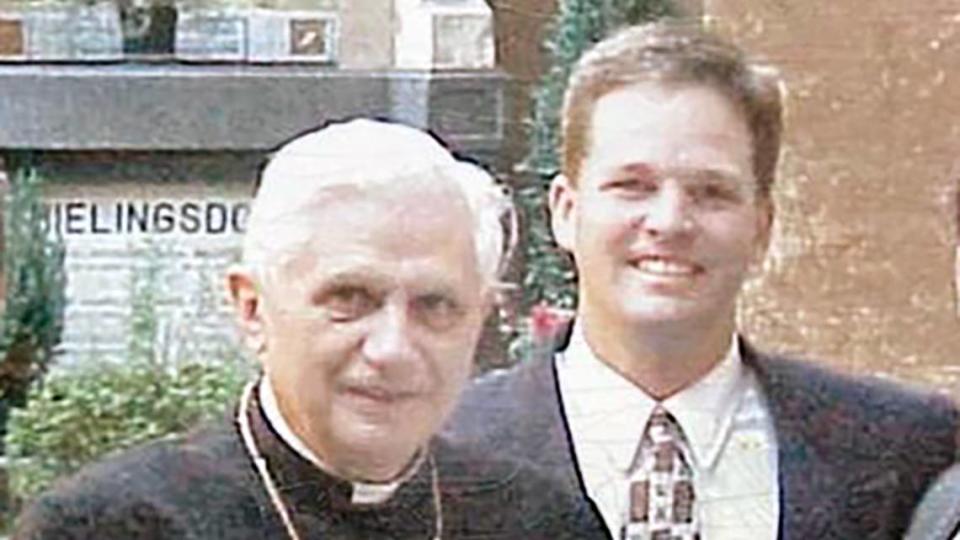

Most Bishop Miege High School students learned by Googling him that their new president, Phil Baniewicz, had once been accused of sexually assaulting a boy in the rectory of St. Timothy Catholic Church in Mesa, Arizona.

No criminal charges were ever filed against Baniewicz, who was hired by Miege last summer. The Diocese of Phoenix settled a 2005 civil suit against him and two priests for $100,000. Both priests accused in the suit pleaded guilty to different crimes involving minors.

One of them, former Father Mark Lehman, is a convicted pedophile who served 10 years in prison for the sexual abuse of a girl at St. Thomas the Apostle Roman Catholic School in Phoenix. He was also sentenced to lifetime parole for the sexual abuse of three other girls and one boy.

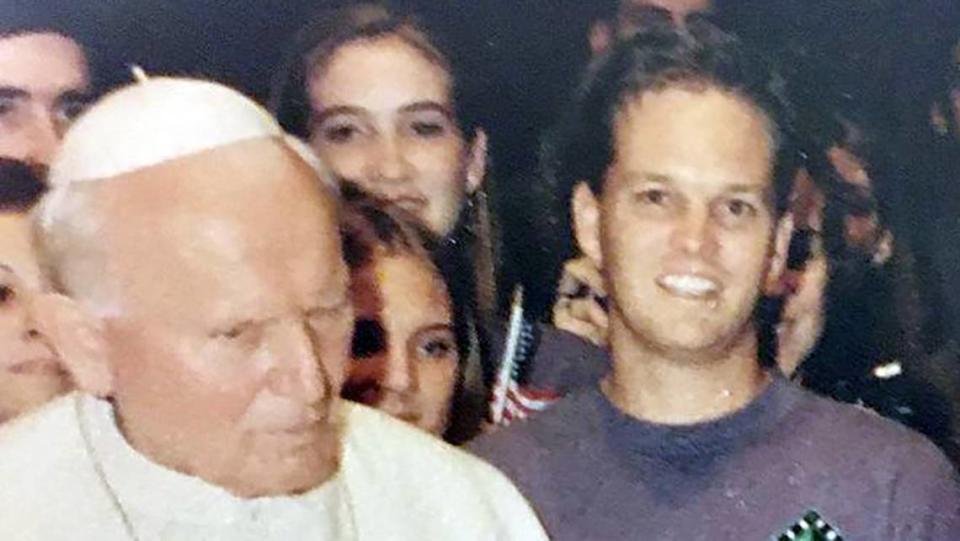

The other man accused in that civil suit, former Monsignor Dale Fushek, describes Baniewicz as “like a son to me” in his memoir, and together, the two men founded a popular charismatic program called Life Teen. Fushek, at one time considered a future bishop, was accused of fondling seven boys and young men and was initially charged with three counts of assault, five counts of contributing to the delinquency of a minor and two counts of indecent exposure.

After one of Fushek’s alleged victims died, he took the plea deal offered by prosecutors and avoided five separate trials by pleading guilty to a single count of misdemeanor assault. The Maricopa County Attorney, Andrew Thomas, said at the time that he couldn’t believe that the crimes in question weren’t felonies.

There’s a serious argument to be made that any school that hires someone who has ever been accused of sexual assault as its president, or its groundskeeper, for that matter, is putting young people at needless risk. But there is also more to know than whether Phil Baniewicz sexually assaulted a 14-year-old in 1985. And it is not solely the sexual assault that Baniewicz was accused of decades ago that makes some Miege students, parents and alums uncomfortable with his hiring.

Baniewicz did not respond to my messages at all, and Vince Cascone, the superintendent of schools for the Archdiocese of Kansas City in Kansas, declined an interview request. But the diocese did send me what it said I was to take as a group response from the school, Baniewicz and the diocese.

It did not address my central question of whether the diocese had ever looked at the environment Baniewicz was bringing kids into in Arizona. Later, in a follow-up email, the head of communications for the diocese professed shock at that question.

Mostly, the response repeated the talking points in the letter to parents sent last summer. But it also said I should not refer to Fushek as Baniewicz’s mentor: “While they worked together and were co-founders of Life Teen, Mr. Fushek was not someone Phil considered to be a mentor. Please make sure to report that accurately in your article.”

The response expressed full support for Baniewicz.

Was Baniewicz both wrongly accused and wrong?

Baniewicz, who is known as an able fundraiser, has always said that he was wrongly accused all those years ago, and since the sexual assault allegation never went to court, that may be right. But he also says that he was exonerated, which is certainly not the case in any legal sense.

And even if Baniewicz did not assault Billy Cesolini at St. Timothy, that would not clear him of all wrongdoing. He’d have to have been living with his eyes closed to have failed to notice what was going on around him in Arizona, in the environment that he did bring kids into.

So was he a poor judge of character, covering up for his Life Teen co-founder, or silent for some other reason?

I’m not sure, but have any of his subsequent employers even looked at the possibility that he could have been both wrongly accused of sex abuse — and again, I don’t know that he was — and yet guilty of enabling predation?

If Miege and other Catholic institutions have looked only at the serious but narrow question of whether or not he did what Cesolini said he did, then they are living with their eyes closed, too.

The real question at Bishop Miege, it seems to me, is this: How much benefit of the doubt should be extended to someone not just accused of sexually abusing a minor, but of facilitating the abuse of others? At what risk to young people, and at what cost to survivors?

The school’s original announcement of Baniewicz’s hiring, last June 30, said nothing about any past allegations. When Miege, which is in Roeland Park, finally did mention them, in a letter to the community, it was only after reporters had contacted the diocese about Baniewicz’s history, as the letter itself said. That letter defending his hiring went out on Aug. 1.

It assured the community that the school’s new president had been fully vetted, first by the former FBI agent hired by Life Teen and subsequently by every Catholic institution where he has worked since then.

Benedictine College, in Atchison, Kansas, which hired him in 2006, “likewise determined that the allegation could not be substantiated,” the letter said, as did Maur Hill-Mount Academy, also in Atchison, where Baniewicz worked for the last 14 years. The letter quoted from his glowing reviews.

The response I received from the diocese this week also mentioned the original investigation for Life Teen by the retired FBI agent, who found the allegations “were not able to be substantiated and were without merit.” The diocese also sent me a letter from Jim Slattery, who as a Maur Hill board member was instrumental in hiring Baniewicz there. He said Baniewicz had saved the school financially and was a scandal-free leader who ensured “that faith in Jesus Christ was a central part of the MHMA educational experience” and inspired “a renewed interest among alumni in generously supporting their alma mater.”

“To continue to rehash this story is terribly unfair,” Slattery added. But my question is whether it was ever fully hashed, and the response of the diocese suggests that it was not.

If a singular focus on that one unproven allegation allowed those vetting Baniewicz to ignore the context in which it was made, then they missed the bigger picture. And if on the contrary those schools did know all of the circumstances surrounding that allegation and hired him anyway, then they were willing to take a lot more on faith than history, both in the church as a whole and at Miege in particular, would say was either smart or sensitive to past victims.

Priest on hiring committee once accused, too

One of those on the Miege hiring committee, Father William Bruning, pastor of Queen of the Holy Rosary Catholic Church and a member of Miege’s board of trustees, was himself once accused of sexual misconduct by a woman who said that Bruning had sexually abused her when she was a student at Most Pure Heart of Mary School in Topeka.

In 2015, church investigators said they could not substantiate that report. When she came forward again, with more information, in 2018, they found her allegations not credible.

As a result, Bruning has said that he knows what it’s like to be unfairly accused. He knows what it’s like to be sidelined by scandal, too. In 2013, Bruning resigned from his position at Prince of Peace Parish in Olathe and was temporarily “prohibited from exercising his priestly duties” after admitting to a report that he had violated his vow of celibacy with an adult.

A longtime employee of the diocese, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said that in some ways, Baniewicz’s narrative of having been unfairly accused probably worked in his favor: “The idea of a false allegation is a good self-protection with clergy. And it did seem like everyone was caught off guard when it hit the media” that Baniewicz had been accused of abuse. When I asked how that could possibly have come as any surprise, this person said, “I’m often surprised at what little coverage there is.”

In the letter Baniewicz then sent introducing himself to the Miege community, he described himself as someone who, in his 30 years of marriage, has strived “always to be an honest, faithful, on-fire man of God.”

He said his favorite Bible verse is, “Blessed are you when they insult you and persecute you and utter every kind of evil against you because of me. … Why? Because I have had to go through a false allegation. As one of the founders of Life Teen, I had a big target on my back. Someone fabricated a story that had no truth, yet I had to endure the persecution. I was exonerated and have continued to work in the Church.”

Baniewicz ‘would never get hired in a public school’

Some of those hurt by past abuse at Miege see his hiring as a personal slap in the face.

Kelly Kincaid, for one. She’s 44 now, but during her sophomore year at Miege, she began being groomed and abused by a teacher and school counselor who was her track coach. When she and her twin sister reported him, as college freshmen, she said, “the diocese didn’t do anything and the administration didn’t do anything. Not one teacher, not one person reached out,” while “I had to get orders of protection and he kept stalking me.”

“We lived in fear for a while,” said her sister, Katie Kincaid-Longhauser.

That coach, Bill Van Hecke, pleaded guilty to the misdemeanor charge of contributing to a child’s misconduct. But it was in part as a result of that case that the Kansas Legislature passed a law making it a felony for a school employee to have sex with a student younger than 18.

Just last July, Miege sent out an email inviting any other victims of Van Hecke’s to come forward.

The diocesan newspaper, The Leaven, echoed that invitation, and ran a piece from Archbishop Joseph Naumann about an official “Day of Prayer in Atonement for Those Harmed by Sexual Abuse in the Church.”

Katie and her mother, Patty Kincaid, attended the July Mass Naumann said for those harmed in that way. “We were feeling, OK, they’re doing the right thing,” Katie said. “But then, they bring in Baniewicz.”

So Naumann’s “words were great,” Katie said, “but his words mean nothing, because his actions are completely the opposite.” Baniewicz, she added, “would never get hired in a public school.”

‘It’s always about the money’

Kelly and Katie’s parents, Don and Patty Kincaid, have been major donors at Miege, where all seven of their children went to school. Even after Kelly’s experience, they didn’t leave the church or stop contributing to the school. “We said we can say ‘see ya,’ or we can try to make it a better school by investing” time, love and money, Patty said. The latter road is the one they took.

But after Baniewicz was hired, around the same time as the Mass of atonement, Don and Patty Kincaid did withdraw their support. “I just decided it wasn’t the right place for me anymore,” Don said, and he resigned from the school’s foundation board after Baniewicz was hired. “Call me long distance, because I’m out.”

Greg Wilcox also left the school’s foundation board over the hiring: “I went to school there and was trying to give back to the community, but the decisions they’re making are not the right ones. When you’re dealing with our kids and our grandkids, you should dig as deep as you can,” and that isn’t what happened in this case, as he sees it. “Then you go get a president of the school who has been accused and money changed hands?”

The only thing Wilcox can figure is that they’re counting on Baniewicz to bring in more money than he’s lost them: “It’s all about money. It’s always about money.”

The joint response I received from Baniewicz, the diocese and the school says at Miege, the new president has already “increased year-over-year enrollment” and “motivated alumni.” It quotes school principal Maureen Engen as saying that her administrative team “loves his leadership.”

The response also said that the diocese, school and Baniewicz take all reports of misconduct seriously, and work to “respond to survivor needs with urgency, respect and compassion. ... Mr. Baniewicz understands that this aspect of his past can cause particular distress to survivors of sexual abuse and their families, which is why he has made a practice of being upfront about this unsubstantiated allegation.”

The school and diocese, however, were not upfront until reporters started calling them.

The statement also says that Baniewicz “acknowledges that in this instance, how he chose to inform his new school community lacked sensitivity and awareness. ‘I apologize for any harm I have caused the survivors of sexual assault and their loved ones by the manner in which I have discussed my past. Their voices should be heard and believed.’”

Only, their voices say that someone with his history is a walking, talking trigger, and no one at the diocese wants to hear that.

In the end, Baniewicz’s Life Teen co-founder Dale Fushek was excommunicated — not for abuse, but for starting a nondenominational Christian church in the Phoenix area, the Praise and Worship Center in Chandler, Arizona.

Fushek was first accused of sexual harassment in 1995, by a former employee in his late 20s, and that civil case against the diocese was settled for $45,000. Almost a decade later, he, Lehman and Baniewicz were accused by a man then in his 30s, Billy Cesolini, of abusing him in 1985. Cesolini accused Baniewicz some time after naming the other two, saying he’d remembered more during therapy. His therapist was the renowned trauma specialist Bessel van der Kolk, author of ‘The Body Keeps the Score.’ Fushek’s lawyer called Cesolini “delusional.”

In 2005, Fushek was charged with 10 criminal misdemeanor counts related to alleged sexual contact with seven teenage boys and young adult men. But then the counts were reduced after one victim died, and in 2010, he pleaded guilty to just one of the charges as part of a plea bargain.

Andrew Thomas, who was Maricopa county attorney at the time, said that what Fushek did should have been on the books as felonies: “But in the end, I’m not a lawmaker — I’m a prosecutor. I’m left with the laws that are written by the Legislature.” Still, “knowing that we had evidence of these crimes, I felt we needed to go forward and needed to charge this defendant, and hold him accountable.” Or try to, anyway.

Book rages against the Catholic Church

“The ex-priest came out very lucky,” said a piece in EastTribune.com after Fushek took the deal, because “none of those sexual horseplay incidents alluded to in court documents, press stories and pre-trial references would get described in an open courtroom. The alleged victims go on living with them as memories of those abusive days in the Life Teen Catholic youth program, co-founded by Fushek” and Baniewicz.

If Fushek was lucky, then Baniewicz was too, because this was the world he brought Life Teen kids into.

Fushek was fined just $250, along with 364 days of probation. In the book he has written, “The Unexpected Life,” he argues that both church and state authorities targeted him in a “witch hunt,” in part out of jealousy.

“If you ask where the dysfunction of priests comes from,” he wrote, “I am sure that celibacy is part of the issue. … Does it come from a lifestyle that is emotionally selfish? I am certain that is also a factor.” In general, he paints Catholic priests as cruel and disloyal: “The basic ideals of any Boy Scout troop don’t find a home in the priesthood. If you want to talk about ‘priest scandals,’ I think how priests treat each other is scandalous.”

Of Pope Benedict XVI, who supported Fushek’s excommunication and formally removed him from the priesthood, he wrote, “You would think someone who joined the Nazi Party in his youth would be merciful towards other people and whatever their mistakes might be. But, I fear the ‘self-righteousness’ of the Catholic church today is very alive, and continues to impact how others are dealt with.”

When Bishop Thomas O’Brien resigned in 2003, after leaving the scene of a fatal hit-and-run, Fushek was O’Brien’s top aide. In Fushek’s book, he also suggests that O’Brien was somehow set up by his enemies within the church.

And Fushek himself couldn’t have done anything too wrong, he reasoned in the book, or else would have gotten more than a measly $250 fine after an investigation that dragged on for years.

He praises Baniewicz, who he says is “like a son to me,” and several others, including Mother Teresa and John Paul II, whose visits to Phoenix Fushek helped arrange.

But much of the book rages against the church, where he goes so far as to say that love is not even possible: “Letting go of the Catholic priesthood was hard for me. It was my identity. But, once I could see that there was no potential for me to LOVE — and no real love in the priesthood of Phoenix — I could move on. My conscience is clear!”

If Miege officials ever read this book, wouldn’t they wonder, as I did, what it means that this is the man who says Baniewicz was “like a son” to him?

‘Baniewicz was feeding the monster’

Cesolini, the man who accused Lehman, Fushek and Baniewicz, is now a well-regarded special education teacher in an Arizona high school. He did not return messages about Baniewicz.

Neither did Jim Partsch, who owns a fiberglass company in Colorado. Criminal charges against Fushek for assaulting Partsch in 1993 and 1994 were later dropped. In 1996, he received a separate settlement of $45,000 from the diocese.

In 2005, Phoenix New Times writer Robert Nelson wrote a long, gritty piece headlined, “Cross to Bare: For 20 Years Dale Fushek Was the Golden Boy of the Phoenix Catholic Diocese. Now, His Golden Boys Are Talking.” In it, he reported that Fushek’s brother priests often joked that Fushek “started Life Teen to get teens.”

And Baniewicz knew none of this? Or did, but chose not to believe it, or did, but kept quiet about it? These are the questions that remain unanswered.

Partsch told Nelson that after he confided in Baniewicz about being abused by Fushek, Baniewicz responded only by betraying his trust, and telling Fushek everything he had said.

Nelson, who these days works as a historian for the National Park Service in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, told me that while there is no proof that Baniewicz himself sexually assaulted anyone, “he definitely brought kids into this aggressively sexual situation” through Life Teen.

“Baniewicz was feeding the monster. Baniewicz was definitely guilty of knowingly sending teens to this situation no parent would want their children in. He called stories that he had to have known were true, lies. After spending so much time talking to people wounded by that scene that Baniewicz promoted,” Nelson said, he feels there’s no question that “him running a school is totally inappropriate.”

Does Miege know that according to his Life Teen co-founder’s indictment, between 1984 and 1994, Fushek fondled boys, walked around naked in front of them, invited one into his bed and asked another to join him naked in a hot tub? Prosecutors also said Fushek conducted “sham confessions” in which he asked question after question about the sex lives of boys for his own gratification.

Any prosecutor will tell you that no other crime is as hard to prove in court as a sex crime, even though false rape accusations are no more common than for any other crime, somewhere between 2% to 10%.

‘Not someplace I feel comfortable sending my child’

In John Patrick Shanley’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play “Doubt: A Parable,” recently revived on Broadway, the audience is never really sure whether Father Flynn, the likable young priest that steely Sister Aloysius suspects of molesting a student, is guilty or not.

Through much of the play, Aloysius seems sure that “when you take a step to address wrongdoing, you are taking a step away from God, but in his service.” Yet in the end, even she second-guesses herself.

The play, which I’ve seen multiple times, is brilliant in part because it’s so true to life: I’ve known women religious who, like Aloysius, were not listened to, and as it turned out were not wrong in their suspicions. Yet as Catholics, we’re taught to doubt ourselves, in ways that can feel so much more compassionate than certainty. Sometimes, that’s the right thing to do. But too often, that doubt has been the predator’s best friend.

A parent whose other children attended Bishop Miege told me that she was not sending her son there next year, when he will be a freshman, because she doesn’t want to take the chance. “It’s not someplace I feel comfortable sending my child. And I should just accept this, move on and not question them because they know what they’re doing?”

“We’re Catholic, and would love to send our kids to Catholic schools,” especially Miege, which is right in the neighborhood. “But when decisions like this are made, I lose a lot of faith, because surely there were other quality candidates. Everything that’s been said is, ‘You need to have faith and pray more.’ But you also need to use the brain God gave you.”

A parent whose child does go there said she’s especially wary after looking into Baniewicz herself. “If you dig further, it gets worse. Yet they put out some easy-to-refute, misleading statements, that he was proved to not have been a part” of any wrongdoing. ”When no, they settled it, like they settle all the time, usually because they’re guilty.” Some parents, she said, “feel hopeless,” and like all they can do is tell their kids, ‘Don’t go in a closed room with this guy.’ We had that conversation and my daughter was, ‘I know.’’’

He ‘didn’t touch me, but he did cross a line’

A current student at the school said, “I do not know very many people who would advocate for him. A lot of us think the allegations are true.”

“I find it hard to believe he’s the outlier” among the three men accused in Arizona. Those who chose him to run her school, she said, “like him because he’s been able to raise a lot of money, and he presents well.”

Initially, “I worked hard to give him the benefit of the doubt because I’m Catholic. But he’s been a little — off — so that made me want to investigate, and now I’m convinced” that he’s not what he claims to be.

“He says he’s very rooted in God, but when he tells others that Catholicism is about...girls not leading others astray” by wearing their skirts too short, that strikes her as a “weird” red flag.

“I don’t think anyone’s gotten more comfortable” as the year has gone on. “This year we had a kid expelled for drawing a racist photo, and the first thing he wants to focus on is skirt length?”

Parker Valdez, a 24-year-old former student at Maur Hill, told me that Baniewicz “didn’t touch me, but he did cross a line of what’s appropriate” when he pulled her out of history class one day, supposedly to wish her a happy 17th birthday.

After office staff left for lunch, she told me, he closed his office door, “so you can speak freely, he said” and “as soon as the door closed, it changed from innocent to an interrogation. He wanted to know names of who I’d been hanging out with. Then he says he’s heard some rumors, and asks me how I plan to stay pure. The conversation had taken a turn I was not comfortable with. Then he said, and this is a quote, ‘Everyone at the school thinks you’re a loose party girl whore.’”

This whole conversation sounds eerily like those that Fushek allegedly had with those boys in Arizona when he pushed them for details about their sex lives.

Valdez, who is now married, expecting her second child and working for her father in Lawrence, was not even sexually active at that point, she says, and in fact had only been on two dates, with a boy two years younger, chaperoned by his parents.

“I’m crying,” in the meeting with Baniewicz, Valdez said, “and to him that’s an indication to take it further. He says he understands I have ‘certain desirable features’ as a young woman, but I’m leading these ‘men of God’ towards temptation and away from the Lord. I asked him repeatedly what I had done, and he kept just saying, ‘You’re a beautiful girl.’ I had never even been dress-coded! And partying with who? How?” He also told her, she says, that as a non-Catholic, she was probably unfamiliar with the virtue of modesty.

Asked specifically about this allegation, the diocesan communications director said that Maur Hill is not a diocesan school, that neither the school nor the diocese had heard anything about this allegation, and that Valdez could and should report it to the abuse hotline. She did not provide any response from Baniewicz.

Known by the company you keep?

Valdez wonders, too, why his connection to Fushek isn’t held against him, or even questioned: “I was always taught that if you don’t want people to think you use drugs, don’t hang out with people who do drugs.” She said Baniewicz regularly spoke about how he had been wrongly accused, along with his “spiritual father” Fushek.

I don’t know the answer, but I do know that a pattern of misplaced sympathy for the accused at the expense of their accusers has not served the church very well over time, and has been devastating to victims.

The now former Father Dennis Schmitz, who in 2002 was sent to prison in Kansas for abusing a 15-year-old boy, was chaplain at Bishop Miege from 1989 to 1994. That was decades ago, it’s true. But what have school and church officials learned since then?

Suddenly, Archbishop Naumann’s apology to victims no longer seems authentic to Kelly Kincaid and others.

Naumann also assigned Father John Pilcher, who’d been accused of molesting a boy in Topeka, but was not prosecuted, to Holy Trinity Parish in Lenexa earlier this year. The archbishop met with unhappy Holy Trinity parishioners, but did not seem to make them feel any better about his decision.

During his homily at a Mass there in January, he spent a lot of time extolling Pilcher’s past success in raising money and getting buildings built. On an audio recording of one of the meetings Naumann held with parishioners after that Mass, a man asked the archbishop to please stop disrespecting him by rolling his eyes.

Some in the Miege community feel disrespected, too. Even after all of the damage done, believers in the main want to stay where they are — where they have felt God, and have history and commitments and relationships of long standing.

But they aren’t as willing to trust the “fully vetted” as they used to be. And they doubt not so much themselves as their shepherds, in ways they should not have to.