Mommy dearest: a psychiatrist puts Donald Trump on the couch

Dr Justin Frank thinks the president has an erotic attachment to his daughter and a fixation with faeces and dirt

It all begins with the mother.

This is the opening line of Dr Justin Frank’s book, Trump on the Couch, “a deep dive into the psyche” of the 45th US president which argues that a distant mother and authoritarian father are key to understanding how Donald Trump became Donald Trump: infantile, impulsive and ill-suited for office.

“Yes, we should be scared,” Frank, a clinical professor of psychiatry at George Washington University, told the Guardian. “We have to accept that he is the president and we also have to accept that he’s never going to change because he can’t. Once we accept those things, we can then figure out what to do with our fears.”

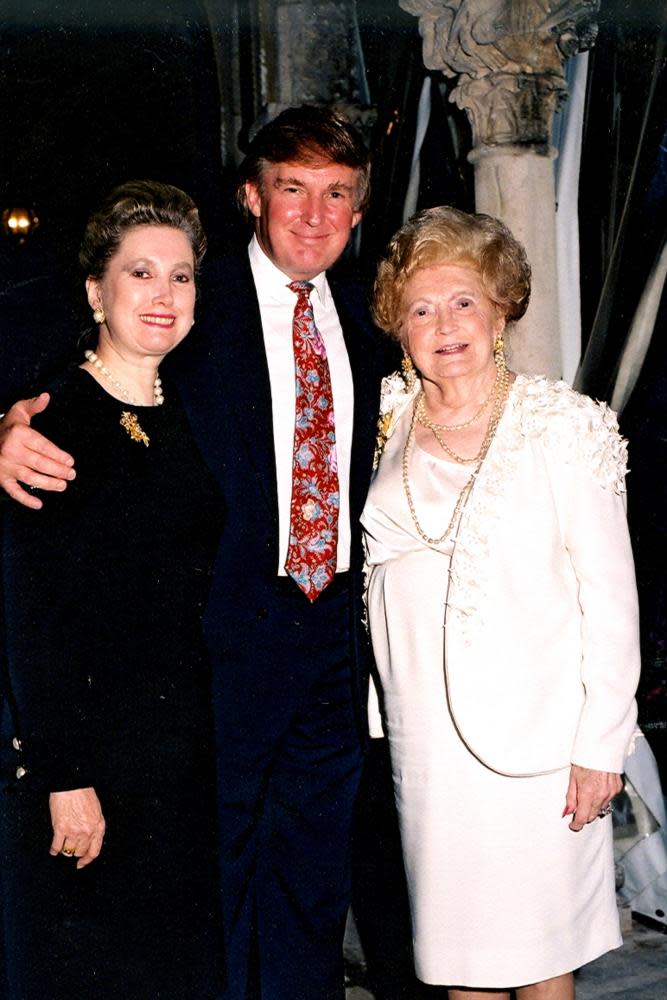

For Frank, the dynamic between infant and mother has a profound influence on a person’s psychological outlook and health. Trump’s mother was Mary Anne MacLeod, who arrived in New York from the Outer Hebridean island of Lewis in 1930. After six years as a domestic worker and nanny, she married the property developer Fred Trump and they had five children.

The otherwise garrulous president has said little about his mother. Notably, for his first few months in the Oval Office, the only photo behind his desk was of his father. His mother was added later. Yet, Frank points out, 72-year-old Trump’s gravity-defying hair is a very deliberate homage to his mum’s.

“The fact that he tries to get us to feel his anxiety and he externalises responsibility makes me feel that, as a young child, he did not feel contained or held by his mother or other caretakers,” he says. “He didn’t have a strong maternal force in his life.

“The one thing we do know biographically is that when he was two, the last child in the family was born, but when his mother went to the hospital she didn’t come home right away. She had a haemorrhage, she had four surgeries and came close to dying and there was virtually no talk about that in the family. His older siblings just went to school as if it were normal while they’re terribly worried about their mother.”

His mother’s frequent absences, Frank suggests, left Trump devoid of empathy.

“One of the things that you do when you’re feeling ignored and abandoned in some way,” he says, “is develop contempt for that part of yourself. You have the hatred of your own weakness and you then become a bully and make other people feel weak, or mock other people to make it clear that you’re the strong one and that you don’t have any needs.

“In fact, at one of his rallies recently somebody was complaining about something and he said, ‘Why don’t you go home to your mommy?’ I was struck that he must have been reading my book.”

Frank adds: “That’s why I think some of his relationships with women are not just based on sex. It had to do with a real contempt for women’s boundaries and autonomy because he’s so angry and so bereft and I think that’s so deeply unconscious.”

Fred Trump: ‘A kind of tyrant’

Trump on the Couch is the third in Frank’s series of psychoanalytic presidential profiles, following Bush on the Couch and Obama on the Couch. It draws on two years of study of Trump’s tweets, speeches, interviews and overall behaviour to conclude that he is “mentally unfit” and “psychologically unsuited” to the presidency. The approach represents a break from the “Goldwater rule”, the principle that bars psychiatrists from giving professional opinions about public figures without examining them in person.

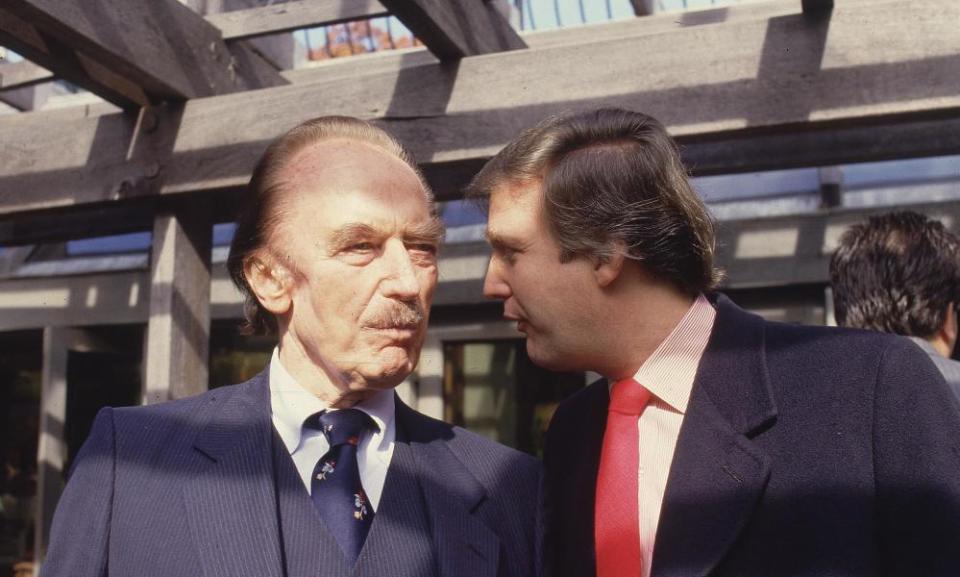

Frank suggests that Trump’s authoritarian father was also a formative influence on his childhood in Jamaica Estates in Queens, New York.

“When his father was there,” Frank says, “he ran the house like a kind of a tyrant, where there were so many rules that everybody had to do what the father said. [Donald Trump] was, I think, frightened of his father. His father would take him aside and say, ‘You have to be strong. You have to be tough. Never apologise. Never complain. Never say you’re sorry. You have to learn to be a killer. You have to be a king.’ It’s over and over again, drilled into him.

“But it didn’t work when he went to school, and his father actually joined the school board because he thought maybe he could help control things – but he couldn’t. When he was about 10, 11, 12, Donny would sneak into New York in a delinquent way and go to shows with a friend of his. Then he saw West Side Story and that got him very excited. He decided to start buying switchblades and developed a fairly elaborate collection of large ones and his father eventually found out and just read them the riot act and made arrangements to send him off to military school.”

Trump manifests what Sigmund Freud identified as “repetition compulsion”, the author continues.

“People unconsciously repeat inner conflicts that they’ve had that didn’t get resolved when they were younger,” he says. “Trump is re-enacting his teenage impeachment fears and is now doing it with [special counsel Robert] Mueller and all these people. He was going to do everything he could to sneak into Manhattan to undermine his father to do whatever he wanted, and now he’s doing it with Mueller. Instead of being thrown out of the Jamaica Estates, he’s afraid of being thrown out of the White House.”

Frank has more than 40 years of experience in psychoanalysis but he acknowledges that he has never encountered a subject like Trump.

“He is infantile. He’s dominated by impulses, by suspicion, by a need to always win, by a fantasy that he has to do everything himself, which is what you see in children when they say: ‘Don’t help me, mommy. I’m going tie my own shoes.’ Then you wait for 45 minutes for the shoes to get tied before you can get out of the house. He’s, like, anti-dependent.”

Does he think Trump is capable of feeling love? “No. He needed his first wife, Ivana, but once they got together he really needed her to be subservient to him, like many men do. So I don’t know about love or real, deep concern for her wellbeing. Love involves being able to have ruth, as opposed to being ruthless. Being able to feel concern and care, and I just don’t think he had that.

“I also don’t think he ever felt loved and I think that’s also partly why he tweets so much and has to say ‘I’m getting an A+ as president’ so often, because if he didn’t get love outside, he’s going to compensatorily love himself. ‘If don’t get love from you guys, I know I’m the best.’”

‘Unconscious incestuous fantasy’

Frank devotes a chapter to the psychology of sexism and misogyny. In it he notes that Trump reportedly told the model Karen McDougal and the porn star Stormy Daniels, with whom he is alleged to have had affairs, that they reminded him of his daughter Ivanka. The psychoanalyst suggests this enabled Trump to enact “an unconscious incestuous fantasy” and use the image of his daughter as “a kind of psychological Viagra”.

Trump’s body and verbal language around Ivanka has often been unsettling.

“I think that he does have an erotic attachment to her,” Frank says, “but he leads with his unconscious so he doesn’t have to be dominated by it. If he gets it out of his system by saying it and joking about it, he doesn’t have to live with it and sit with it. It’s like releasing a pressure cooker. He has the courage of his neurosis.”

Then there is the mendacity. According to the Washington Post, Trump has made more than 5,000 false or misleading claims since taking office.

“I think that most of the time he does believe the things he’s saying,” Frank says, “because, at his deepest level, he lies to himself. The purpose of lying is to hide yourself, first, from others, but then at a deeper level to hide yourself from yourself.

“He doesn’t want to look at who he is, so what he does over time is distort reality, and lying involves changing reality and making it into one’s own wish or fantasy. That’s where the term ‘fake news’ is so important, because he hates the fact that the news functions almost for him unconsciously like a Greek chorus. Part of his lying is also to deny rules and deny regulations, to deny laws, to deny limitations. It’s rejection of learning and thinking. Rules remind him of having to accept truth.”

As for Trump’s scattergun tweeting, Frank has an unusual metaphor.

“It’s a form of what I call the faecalisation of the environment. He is covering all of us with his productions, which I think unconsciously have a faecal quality. They’re smearing things in a playpen all over the place. It’s something that we see in young children who are both exuberant and angry at the same time.”

He expands: “He talks about shithole countries, he talks about shit, he talks about dirty Mexicans, people who are dark and dirty. Those are all related to germ-phobia and related to his own faecal fantasies and issues.”

Trump is the most powerful man in the world and arguably the strangest American president of all time. Yet novelists might struggle with his shallowness and lack of hinterland: he would not necessarily make a great literary character.

Frank muses: “He’s quite two-dimensional. I don’t think I could really ever engage with him. I would not find him a good patient or subject for a novel. He doesn’t have the depth and I think that, if he were not president, I would never think twice about him.”