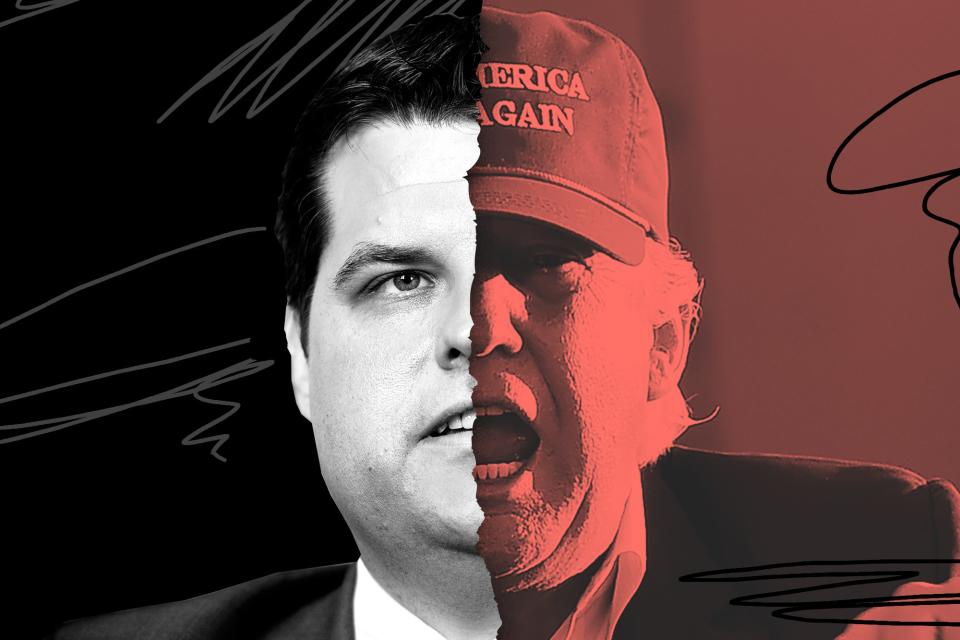

Matt Gaetz Is the Trumpiest Congressman in Trump's Washington

Matt Gaetz did not set out to go drinking, with a journalist, on the record. Nonetheless, here he is, plunked down at the Capitol Hill watering hole Bullfeathers, ordering a pint of beer.

Gaetz, a freshman Congressman, would like the record to reflect that he "vigorously protested" this idea. At 35, Gaetz is one of the youngest lawmakers in town, but he is old enough to know that an article like this—one that begins with him on a barstool—is bound to be used against him by his political enemies.

But what the hell.

Gaetz had been scheduled to appear on cable tonight, but got bumped from Tucker Carlson's show at the last minute, freeing him up to go drinking. But he'll be back on TV soon enough, continuing the outspoken campaign of provocation that is earning him notoriety far outside his Florida Panhandle district. In recent months, no hot-button topic has seemed off limits for the rookie lawmaker who's appeared on TV to call for the firing of Robert Mueller, relentlessly taunt Attorney General Jeff Sessions, and voice support for President Donald Trump's assessment that some developing nations are shitholes.

In January, Gaetz set off a prolonged media firestorm when he invited a notorious Internet troll known for posting statements online questioning the history of the Holocaust to be his guest at the State of the Union. He's expressed some regret about that decision, but generally stood by his attention-grabbing approach. Washington, meanwhile, has taken notice.

Gaetz is tall, clean-cut, and sturdy—he's conscious of his weight—with chestnut hair and deep-set eyes, his face vaguely evocative of a bulldog or a pug. He's not married, a rarity for a politician and a fact that gets remarked upon now and then. He told me a story about that. Once, at a party at the Florida governor's mansion, he introduced his date to Governor Rick Scott. "Why aren't you married yet?" Scott teased him. "Well, Governor, Gaetz shot back, 'You vetoed alimony reform.' "

When I asked Gaetz what his date had thought of his alimony zinger, he said, "I don't think she knew what alimony was." Then he said, "She's this Cuban girl." Then he did an impression of her asking him, " 'What is thees alimony?' "

Gaetz does an impression of Trump, too, one that is about as good as Alec Baldwin's, which isn't saying much. Unlike Baldwin, though, Gaetz is in regular contact with the president—sometimes twice a month or more, he says. It's an unusually high level of access for a first-term congressman, and this relationship goes a long way toward explaining why Gaetz feels so free to run amok on Capitol Hill.

sotu_TW056_013018

Once upon a time, as a freshman lawmaker in Washington, you could be expected to keep your head down, learn the ropes, and avoid anything—telling off-color jokes to reporters, slagging your own party's attorney general, inviting a suspected Holocaust skeptic to the State of the Union—that might unnecessarily rile the leaders of your caucus or the voters back home.

But in Trump's Washington, Gaetz's example suggests a new path for young politicians on the make: Court controversy, soak up national media attention, and damn the consequences, so long as you remain in the good graces of the president (or, for Democrats, in his bad graces).

Gaetz has been with Trump since the start—he endorsed him early and stuck with him through the darkest days of the campaign. And in recent months, he's doubled down, emerging as one of Congress's most vocal and aggressive opponents of the investigations into the president's relationship with Russia.

He argues that his approach isn't just a ticket to national notoriety, but one that confers real authority. Being the sort of guy who can whisper into the president's ear confers its own sort of influence. "He knows who I am," Gaetz said of Trump, "and he doesn't want to screw me."

Besides, Gaetz argues that being controversial has its benefits these days; the only real sin in Trump's Washington is to be boring. "The organizing principle of today's politics is 'stay interesting,' " he told me.

Courting controversy, of course, means making enemies, which is just the sort of thing that typically spells trouble for a young member of Congress.

"I think he's just on a collision course with disaster," said one establishment Republican operative who has watched Gaetz's swift rise with the expectation that an equally swift fall is likely not too far off.

The proposition Matt Gaetz seems willing to test is a straightforward one: Has he cracked the new code for getting ahead quickly in Trump's Washington, or has he simply found a shortcut to a spectacular downfall?

Gaetz has had an unusually long time to ponder the possibility of a Trump era in Washington. Back in 2013, at a meeting with Roger Stone, Trump's notorious dirty trickster told Gaetz, in no uncertain terms, that the mogul would become the president. "I thought he had gone one toke over the line," Gaetz said of Stone, a relentless advocate of marijuana liberalization and a fellow Floridian.

In those days, pot was central to his relationship with Stone, whom he calls his "cannabis consigliere." Gaetz was a state representative then, and marijuana was his signature issue—one he pursued with clever help from Stone. It was Stone, Gaetz recalled, who advised him to keep the word "cannabis" off his committee agenda when first raising the issue of medical marijuana—relying instead on vague euphemisms so that party leaders could not intervene to prevent the issue, still taboo among Florida conservatives, from coming up for debate.

Gaetz continues to champion marijuana liberalization in Congress—under Stone's continued tutelage. But his talent for provocation was on display long before he met Stone. In college, at Florida State, Gaetz was nicknamed the "agitator-in-chief" and became well-known for seeking confrontation with campus liberals. "Matt was always the guy that was aggressive and never shy about being in people's face," recalled Christian Ulvert, a Miami-based Democratic consultant who served with Matt in student government.

Mo Roberts, who participated in Model UN with Gaetz at FSU and later took a bar exam prep class with him, found him to be "overconfident," with a surprising "level of ignorance" about the world. Roberts, who was born in Guinea and grew up in Sierra Leone before immigrating to the United States, said Gaetz seemed surprised to be studying alongside a West African immigrant. "He thought my story was unique," Roberts said. "I don't think it's unique at all." He said Gaetz once asked him if he came to the United States in a boat.

Following in the footsteps of his father, who served as president of the Florida Senate, Gaetz jumped into politics early, getting elected to the Florida House in 2010, at the age of 27.

GOP FBI MEMO

Bloomberg/Getty ImagesWhile his father is known as a staid member of the state's Republican establishment, Gaetz quickly earned a more rambunctious reputation in Tallahassee. He staked out a hardline position on the death penalty, including support for the return of firing squads (Gaetz maintains it's actually the "most humane" form of execution).

He continued earning notoriety beyond regular business hours. At one point, he got himself sued when his dog, Scarlet, bit a man in the face at a restaurant in Tallahassee. At another point, he was among a group of state lawmakers implicated in vaguely described "unruly" behavior during a Republican Party retreat at a hotel at Disney World.

Undeterred by any of this—or by an unflattering mugshot floating around from a 2008 DUI charge (which was dismissed)—Gaetz ran for Congress in 2016, seizing on the populist moment while voters were swooning for Trump. Deep into the campaign season, when other Republicans with more to lose were keeping their distance, Gaetz held close to Trump—appearing with the candidate and speaking at Trump rallies whenever he could.

They won election on the same day and both quickly set about making a stink in Washington. A month after being sworn in, Gaetz introduced a bill to abolish the EPA, an audacious proposal for any lawmaker—let alone the new guy—and one with absolutely no chance of passage.

It is often difficult to tell whether Gaetz is legislating sincerely or legislating with tongue in cheek. Over beers, Gaetz conceded to me that the EPA bill was the latter, a way to highlight his beefs with centralized regulation. "I was making a statement," he said.

In November, Gaetz called for Mueller's firing, likening the special counsel's probe to a "coup d'état."

Trump, who adores loyalty, has taken notice. In December, the president returned to Gaetz's district for a rally in Pensacola. He brought Gaetz along on Air Force One and invited him to give introductory remarks at the event.

Backstage, the bonding continued. After the last warm-up act concluded, the loudspeakers at the Pensacola Bay Center began blasting "Let's Spend the Night Together" by the Rolling Stones. "You hear that?" Trump asked Gaetz, just before walking out to take the stage. "It's the Stones. Only Trump gets the Stones."

A visitor to Gaetz's Capitol Hill office gets a sense of the congressman's priorities as soon as he or she enters. Just inside the door, a flatscreen monitor mounted on the wall displays the congressman's mentions on Twitter, streaming in real time. That TV lit up spectacularly at the end of January, when Gaetz took Charles Johnson—a right-wing Internet troll—to the State of the Union.

The resulting firestorm prompted a rare expression of regret from Gaetz. Of course, when such controversies envelop the president's allies, he tends to appreciate them all the more. A week after the State of the Union, he sat down with me at his office. Leaning back in an armchair, his chief of staff looking on, Gaetz argued with great assuredness that the attention was a good thing.

For a few days, he wasn't invited on Fox, but soon his ubiquity on the network was restored. To hammer this home, Gaetz later texted me a photo of a bank of televisions featuring various cable channels in primetime. There, broadcasting simultaneously, was Gaetz's face, beaming from Fox News and Fox Business Network. One interview was live, another had been taped.

"If you could confirm that Melania thinks I'm good-looking," he told me, "that would be awesome."

He clearly appreciates the fame-making aspects of being on TV—and in Trump's corner. But Gaetz points out that there's also political benefit. Keeping himself on Trump's radar and in Trump's ear helps his constituents in Florida, he says.

For example, in January, when Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke announced his intentions to open Florida's waters to offshore drilling—an unpopular move in a state still coping with the effects of the BP oil spill—Gaetz implored the president to intervene. "He told me he would act very strongly for me on that, and he did," Gaetz said. (It's not clear what role Trump played in altering Interior's plans, and the White House did not respond to a request for comment on this story. After meeting with Governor Scott, Zinke announced he was exempting Florida from the new policy.)

Often their conversation is less weighty. Gaetz recalled one recent exchange with the president with particular fondness—a chat that proves the flattery between the men runs in both directions. "He called me, he said, 'Melania just saw you on Fox & Friends. She came in the room, she said there was some really good-looking guy making good arguments,' " said Gaetz, channeling his Baldwin-caliber Trump impression. The memory prompted a request for me. "If you could confirm that Melania thinks I'm good-looking," he told me, "that would be awesome."

93938784

Win McNamee/Getty ImagesOn a Wednesday in March, I met Gaetz again in his fifth-floor office on Capitol Hill. As he had the first time I visited, Gaetz clutched a Diet Pepsi and wore a striking pair of wingtips—dark blue at the heel and the toes, with beige in between. His mother sent them to him, he said, joking that they help her spot him on C-SPAN.

The office was dominated by the presence of a whiteboard that had not been present a month earlier. It was covered with scores of colorful sticky notes organizing the operations of his office. One pale blue sticky said, "Daily polling 4 Russia / FBI / DOJ / memo / Mueller," an orange one said, "Mnuchin statement Friday on Hezbollah," and a pink one stated, cryptically, "Cannabis in HVAC." (It turns out this referred to the House Veterans Affairs Committee and not some scheme to fill ventilation systems with weed fumes in buildings nationwide.)

Gaetz explained that he was recently inspired to institute the board after seeing one used to great effect on an episode of HBO's Silicon Valley. He said that, just as on the show, after encountering initial resistance, the board system was working. Never mind that the show is a satire.

I asked Gaetz if he had any more brilliant management innovations in the works, and he informed me that in addition to trying to force all of his staffers to ditch their scattered desks and work around a shared table, his aides were working with a consultant from the United States Botanic Garden to fill the office with plants.

"I do not believe there's enough oxygen in this office," he deadpanned.

As in so many other instances, it was difficult to discern the extent to which the congressman was being sincere and the extent to which he was, for lack of a better word, trolling. My lips began to curl into a smirk. His lips began to curl into a smirk. Kevin "Kip" Talley, Gaetz's solemn chief of staff—a former cigar lobbyist—remained stone-faced and began listing the numerous benefits of flora in the workplace. "Increases concentration," he said. "Reduces noise."

The other new addition to Gaetz's office was more subtle: two coasters on his desk bearing caricatures of Trump and Speaker of the House Paul Ryan. Gaetz said he snagged them after a recent date at Off the Record, the basement bar at the Hay-Adams Hotel, just across Lafayette Square from the White House.

Then Gaetz complained, unconvincingly, that his heightened profile was harming his dating life, lamenting that just two nights earlier he brought another date to the Trump Hotel, only to be interrupted by well-wishers asking for photographs. "It's hard to go out in this town without reading about it," he said. It is especially hard, he might add, when you tell reporters about it.

In the words of conservative radio host Trey Radel, "Matt Gaetz has balls."

Also at the Trump Hotel that night was Sebastian Gorka, the baritoned wild man who briefly served in the White House as a national security adviser. He said hello to Gaetz, too. Earlier that night, Gorka had dined at the White House with Trump and Fox host Jesse Watters. What he wanted to tell Gaetz was that Trump had singled out three congressmen for praise—California Republican Devin Nunes, Freedom Caucus co-founder Jim Jordan, and Gaetz. Over a White House meal that included roast heirloom cauliflower and milk-chocolate mousse, Trump had—Gorka told Gaetz—marveled at Gaetz's relentless television appearances, calling him a "machine."

Gaetz's life outside the office isn't limited to interrupted dates and chance run-ins with Gorka. He says he also recently shared breakfast with Erik Prince, who wanted to chat about Bitcoin. He also says he received an invitation from Congressman Dana Rohrabacher to dine with him and disgraced former lobbyist Jack Abramoff. Uncharacteristically, Gaetz declined.

After chatting with me for a while in his office that afternoon last month, Gaetz called a half-dozen young staffers in. He wanted them to watch a video he was considering publishing, in which he challenges California Representative Adam Schiff—the Democrats' bulldog on the House Intelligence Committee—to support a bill that would give the president the power to appoint the judges who oversee surveillance cases. The video points out that Schiff had filed a similar bill in 2013, when Obama was president.

Gaetz wanted his staffers to tell him if the one-minute video was excessively "trollish."

"Too much or just right?" he asked, flipping the ultra-widescreen monitor on his desk around to face outward toward them. The staffers, perhaps saving their political capital for the fight over losing their desks, unanimously raised their hands in support of publication.

98726040

Alex Wong/Getty ImagesThe rest of that afternoon, Gaetz allowed me to shadow him as he tended to the business of the citizens of Florida. Most members of Congress would not blithely grant this level of access to a journalist. But in the words of conservative radio host Trey Radel, "Matt Gaetz has balls."

Radel has known Gaetz for several years. He was once a brash young Florida Republican congressman himself. He lasted about a year in Washington before getting busted in a DEA sting buying cocaine in DuPont Circle and resigning in 2014.

Having gone through that wringer, Radel has a warning for Gaetz: You have a target on your back. "When you do raise your profile like that," he said, "there's going to be a whole lot more people who are going to target him for political purposes and attempt to find any way to bring him down."

Roger Stone is less worried about Gaetz's future. "The reason he's going to go far in politics is he's got balls," he said, echoing Radel's assessment of the congressman's private parts.

Nonetheless, Stone cautions that Gaetz has stirred the resentments of his colleagues. "There are those members of the House who are jealous," he said. "They don't have the courage to say something themselves, but they resent it when somebody else does."

Not that Stone is advising Gaetz to tone it down. Gaetz told me Stone's feedback on his anti-Mueller crusade has amounted to a single mantra: "More cowbell" (Stone said he has not advised Gaetz on the matter).

In addition to ribbings from his colleagues, Gaetz conceded his higher profile has come with an uptick in death threats.

Gaetz sees little downside in his approach. He said he has heard mostly words of encouragement from his fellow Republican members, and a few words of advice about honing his message.

Resentful or not, Gaetz's colleagues are hyper-aware of his outsize media profile.

"Matt Gaetz talking to the press? I've never seen that before," cracked Missouri Republican Billy Long when he caught sight of Gaetz kibitzing with reporters outside the House chamber as members streamed in for a vote. "You got your makeup on?" asked Kentucky Republican Thomas Massie right after the vote, alluding to the telltale trace of a recent TV hit as he touched his index finger to Gaetz's forehead.

In addition to ribbings from his colleagues, Gaetz conceded his higher profile has come with an uptick in death threats. He sounded excited to tell me about his "favorite" threat, until Kip—the former lobbyist—insisted on cutting him off.

Later, wandering the halls of the Rayburn House Office Building, we more or less barged into a meeting in the office of Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, another Florida Republican. Gaetz wanted to show me some old leather chairs he hopes to inherit when the congresswoman retires at the end of this term.

The chairs, Gaetz claimed, were over a century old and stuffed with the hair of horses that congressmen used to ride around Washington.

"Don't believe anything he says," Ros-Lehtinen told me. Then, after looking the congressman over, she spotted the wingtips his mother had purchased. "Matt, I just don't know what to say about those shoes."

Gaetz, Ros-Lehtinen, and the constituents she had been meeting with gathered up to pose for a photo.

The constituents were family members of a boy suffering from a rare disease. "He's a great kid who's adorable who has all sorts of issues," explained Ros-Lehtinen solemnly, "which is the same thing we say about Matt!"

But Gaetz could not stay to shoot the shit for long. He had pressing business to attend to back at his office, where aides had prepared a sheaf of constituent correspondence and other tasks for him to address.

Gaetz seemed to find one letter, from a county clerk in his district about daylight savings time—presently a hot issue in the Florida legislature—particularly dumb, and dictated to his staff his sarcastic response: "Thank you so much for your input. Please describe in great detail how daylight savings time affects the operations of the Santa Rosa County clerk's office." Trolling, as it were, a constituent.

Then Gaetz's final appointment of the day, Seth Adler, host of the Cannabis Economy podcast, arrived to tape an episode.

"I dig the shoes, man," Adler remarked upon entering (Gaetz told me that he wore a similar pair, but in black-and-white, to the White House holiday party, and that Ivanka Trump was impressed), and the two sat down on a couch opposite Gaetz's desk to record. After the pair yakked about the wonders of cannabis for the better part of an hour—not your typical congressional meeting—Kip entered to deliver the news that Tucker Carlson had canceled. Gaetz agreed to hit the bar instead, and Adler decided to tag along.

Over at Bullfeathers, somewhere between the alimony story and the second round of beers, Representative Mark Sanford entered the bar wearing not a suit but a blue fleece jacket, as if he had just walked in off the Appalachian Trail.

That's where Sanford's aides said he was, hiking the Appalachian Trail, in 2009, when he was governor of South Carolina and he suddenly disappeared without a trace. In fact, Sanford had flown off to Argentina to visit a mistress, leaving the state and his family in the lurch.

The state legislature censured Sanford, and the scandal seemed to have ended his once-promising political career, at least until he returned to Congress in 2013, a comeback that put him in place to fondly receive Gaetz—who left his barstool and walked over to greet his senior colleague—on this recent Wednesday night at Bullfeathers.

Perhaps Sanford's budding comeback—like Trump's Teflon deflection of scandal—has helped convince Gaetz that even if he does stumble into catastrophe, he'll have a few political lives left to live.

Or perhaps the sight of Sanford actually chastened him, because when Gaetz returned from greeting the South Carolinian, he declined to disclose the substance of their banter.

This, of all things, Gaetz decided, was best left off the record.

Ben Schreckinger is a writer in Washington D.C.