Mark Woods: After lifetime at the beaches, he's sharing an appreciation for science and sand

The annual Opening of the Beaches is next week. If some of the third graders at Neptune Beach Elementary head to the beach, they may look at it a bit differently.

They won’t simply see miles of sand.

They’ll see ancient mountains.

They’ll see gold and rubies.

They’ll see toothpaste and titanium.

They might even see the white “S” on Skittles.

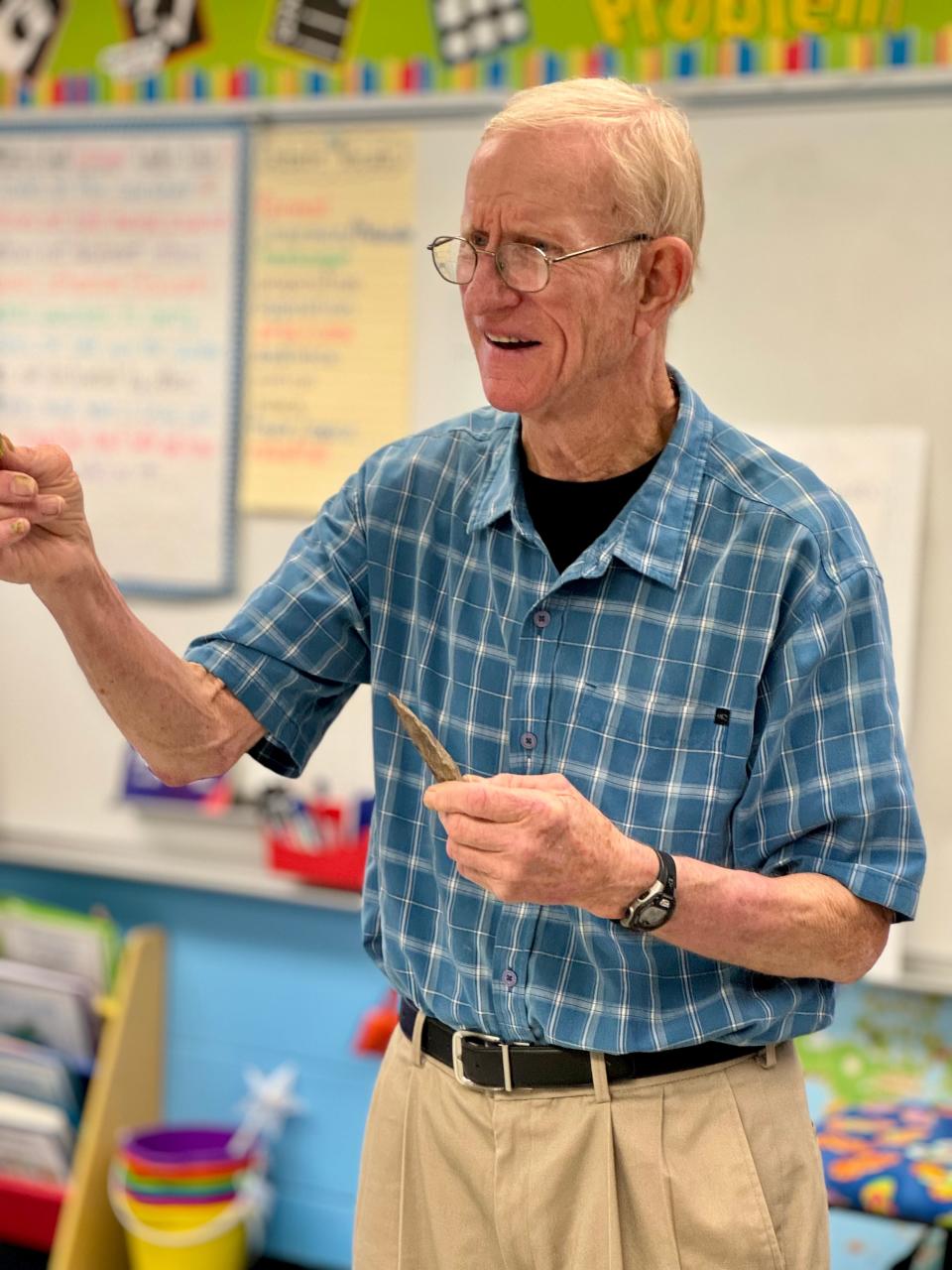

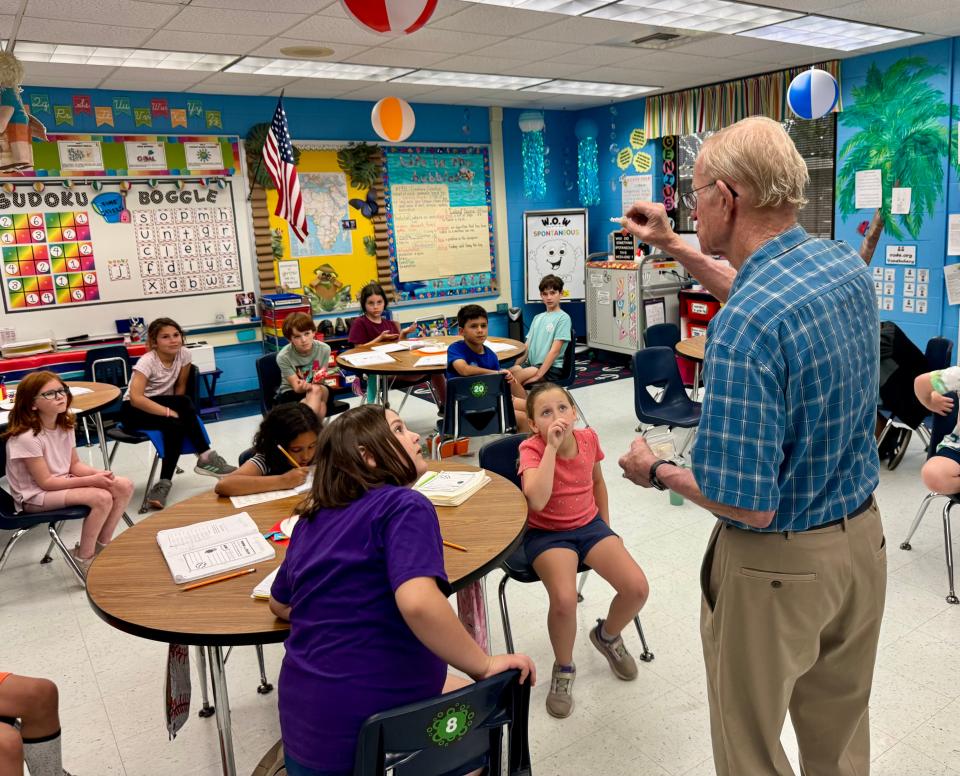

That’s how Bill Longenecker recently began a program in Ms. Peterson’s third grade class: by handing out Skittles.

“You may eat it if you wish,” he said, as he walked from table to table, giving each student a small packet of the multicolored candies. “But you don’t have to take part in this experiment. It’s all in the name of science.”

'Retired Mountains'

It isn’t just the Neptune Beach third graders who will look at the beach a little differently.

There are hundreds, maybe even thousands, of kids in Jacksonville who might think about our sand (and more) a bit differently, thanks to someone who, at age 76, seems like a piece of the beaches.

Longenecker, who grew up at the beach, has been recording daily surf reports for 40 years and counting. For decades, he wrote freelance columns for the Beaches Leader and Shorelines. And while he’s retired after 42 years as a paramedic, he has continued to stay busy and involved. He volunteers twice a week in the ER at Beaches Baptist and goes to schools to talk to students about science.

“My goal is to help them understand science surrounds us,” he said. “It’s not just something to memorize for a test.”

He has done his science programs — about everything from atoms to snakes to our hearts and brains — at about a dozen schools. But it seemed fitting to join him at Neptune Beach Elementary, a school where he’s been doing programs for more than a decade, giving the program he has titled, “Our Beaches: Retired Mountains.”

Gold on our beaches

He emptied a large container full of items. Smaller plastic containers full of rocks. A sheet of paper with mineral specimens. A microscope. A flint arrowhead. A pearl necklace. Old photos. Colgate toothpaste. Tums. Ajax cleaner. A bag of sand.

“Raise your hand if you’ve ever gone to the beach,” he said, standing in the middle of the classroom, holding a bag of sand.

He asked the students if any of them had ever eaten beach sand, not by accident but because they wanted to. A few raised their hands. One girl said, “That’s disgusting.”

“OK, how many of you just ate a Skittle?” he said.

Hands shot up.

“Congratulations,” he said, holding up a small rock. “You just ate something that has this lovely rock in it, called rutile, titanium dioxide.”

He explained that it can be found in all kinds of household items and foods, from sunscreen to Skittles. And then he described one of the places you might find rutile, as the heavy mineral in beach sand.

“Have you ever walked on the beach and noticed that there are different colors of sand?” he said. “Especially after a nor’easter, there are long bands of dark sand. People used to think that was pollution. Where did our beaches come from?”

A boy answered: rocks that used to be huge boulders?

“Good,” Longenecker said. “And where were those huge boulders?”

He asked if they had ever been in the mountains of Georgia, Virginia and North Carolina. He explained that about 20,000 years ago, when the last Ice Age ended, it scraped the mountains down to what they are today and flushed dozens of minerals to the coastline.

“You even can find gold on our beaches,” he said.

He asked if anyone had a large paper clip. One of the students found one for him. He held it up and said if it were solid gold, it might sell for $50 to $75, depending on the day.

“That’s how much gold is on our beach,” he said. “If I chopped it up into thousands of pieces and spread it from one end of Neptune Beach all the way to Jacksonville Beach, you’d never be able to find enough of it to make any money.”

A billion years old

But the dark sands do contain minerals, like rutile, that in the past led to mining. Once upon a time, Ponte Vedra was known as Mineral City. And when Longenecker’s family moved to Northeast Florida in the early 1950s, he remembers seeing huge white sand dunes behind Regency Square.

Longenecker, who for many decades was an avid runner and cyclist, held up a piece of a bicycle frame, a titanium tube. He explained the metal was chosen because it resists corrosion from weather. Then he tapped one of his knees.

“I have an artificial knee and part of it's titanium — not necessarily from our sand, but from beach sand,” he said.

He held up another rock and asked, “Where’s the closest limestone?”

One of the boys earnestly gave an answer that was hard to dispute.

“In your hand?”

Longenecker laughed. He said that was a great answer, but not exactly the one he was looking for. He explained that about 25 to 50 feet down, you can find the backbone of Florida: calcium carbonate, limestone.

He asked the students if any of their parents had ever said something like, “I told you a million times to clean up your room?”

“That’s a bit of an exaggeration,” he said. “But this is not an exaggeration. Another mineral on the beach is zircon. … The rock I’m going to pass around could be a billion years old. Everybody uses these big numbers and nobody thinks much about it. So let’s do a little math.”

He asked the students to snap their fingers, once a second. He asked them how many times they would snap them in a minute, then an hour.

“Now if you wanted to snap your fingers a million times, once a second, it would take 12 days, counting night and day,” he said. “Can you guess how long it would take to reach a billion?”

After a few guesses, all far too low, he gave the answer: nearly 32 years.

“This rock could be as much as a billion years old,” he said. “And yet it’s part of the sand on our beach.”

He set up a microscope for the students to look at grains of sand. One girl, Avery, was so excited by what she saw, she kept insisting that I had to look, too.

Longenecker told the kids about quartz. He explained lithification. He showed them squeezed sand, called mudstone, that came from Hanna Park and has the backbone of a whale in it. He showed them a small tube-shaped fulgurite, and said this is what can happen when lightning strikes sand.

And, finally, at the end of his presentation, he introduced another kind of fossil, a newspaper columnist, and asked if any of the young students had heard of newspapers.

“My grandpa has one,” one girl said.

I asked the kids to go around the room and tell them what they found interesting. Emma pointed to zircon being a billion years old. Makenzie said the gold and rubies on the beach. Brandon talked about Longenecker showing how you can rub two pieces of flint together to make sparks. And Grady went back to the start of the program.

“There is a type of rock that is in candy, toothpaste and more — mind blown,” he said. “And it also kind of ruins Skittles for me.”

mwoods@jacksonville.com, (904) 359-4212

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Longenecker wants Jacksonville students to appreciate science, beaches