So Many Are Searching for This Missing Black Woman — But Not Chicago Police

Capital B is a nonprofit news organization dedicated to uncovering important stories — like this one — about how Black people experience America today. But we can’t publish pieces like this without your help. If you support our mission, please consider becoming a member by making a tax-deductible donation. Donate today.

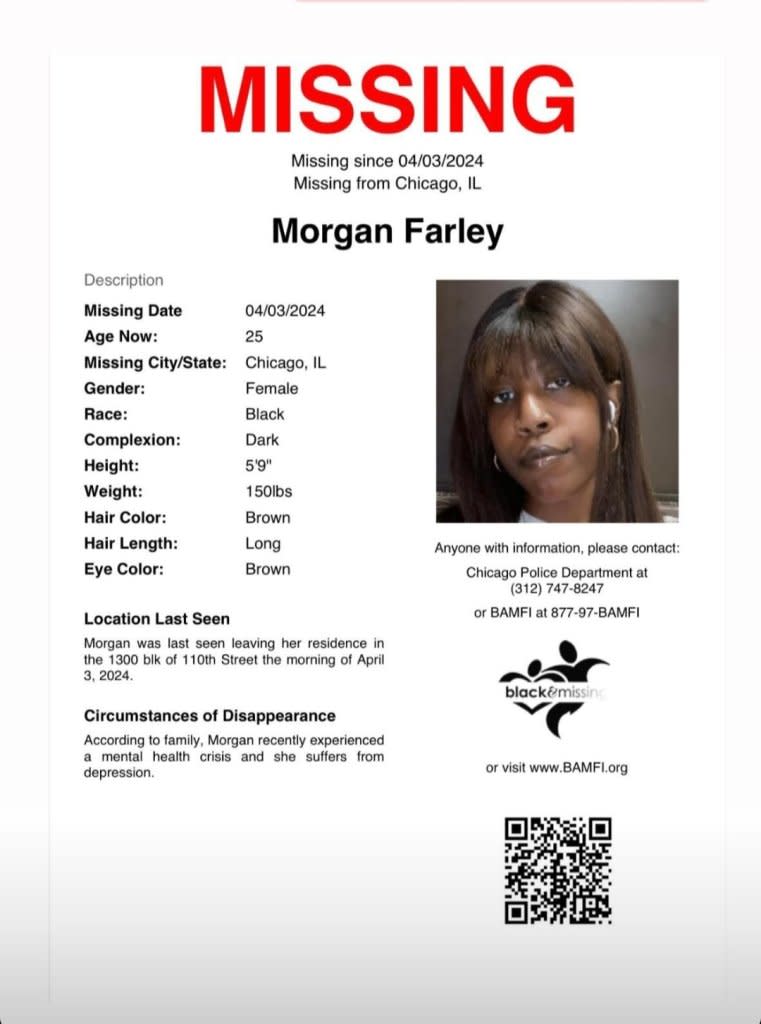

On the morning of April 2, Morgan Farley was wearing a brown wig, light blue jeans, a brownish jacket, and gym shoes while dicing a potato on the kitchen counter inside her Chicago home. She was preparing breakfast for herself as her father, Sam Farley, headed out the door for work.

They didn’t utter a word to each other — not unusual, her father thought.

When Farley returned home that night, the potato had oxidized and browned. “It was still sitting there. … I had to throw it away, clean it up,” he told Capital B. “I haven’t seen her since.”

The following day, Farley went to a nearby Chicago police station to fill out a missing person report — the form is not available online, and he wasn’t sure if the myth to wait 24 hours was true. He filled out the generic questionnaire and included that his 25-year-old daughter had recently experienced a mental health crisis and was diagnosed with depression.

Farley was handed a business card with a number to call and sent on his way. That was it.

For days, Farley obsessively educated, and sometimes frightened, himself with each article and video he read or watched about the rising number of missing Black women across the country. Turning to the Chicago police for help didn’t ease his discomfort. Over the past two weeks, Farley felt what many other Black families in the Windy City have experienced when reporting their loved one missing — dismissed and mistreated.

Feeling discouraged, Farley quickly realized that he needed more hands on deck to help find his only child. The 58-year-old made difficult phone calls to let the family know his daughter had disappeared. He also contacted his prayer circle to keep him uplifted.

“We really want her to come home,” Morgan’s sister, Whitney Wade, told me. They share the same mother.

“Everybody’s looking for her”

Wade, 37, a program officer for a Chicago-based women’s foundation, did not have a clue on where to start looking for her little sister and was frustrated with the lack of communication from the police. While she isn’t naive about police officers’ workload, she also understands someone who looks like her and Morgan may not be considered a top priority.

“She’s an adult. She left on her own. She’s not a child. She’s not a senior. She’s not in any imminent danger. She’s a Black woman, which means she’s low on the priority list for them,” Wade said.

As soon as Wade was able to gather her thoughts, she posted a photograph of Morgan with a caption letting all of her social networks know that her sister with a beautiful smile was missing.

That day, Sylvia Snowden, a local journalist who grew up with Wade, reposted her friend’s appeal to her thousands of followers. She was immediately moved and thought about what her family felt when no one knew where her college-age brother was for a full day. She wanted to do whatever she could to help Wade, so she hit the share button. Later, Kelsey Riley, a project manager, was casually scrolling through Facebook and landed on Snowden’s post. Riley’s heart sank into the pit of her stomach.

The women are friends in real life. Their hearts broke for Wade. Hours later, a group chat and an ad hoc search team was created with Wade. The trio became their own detectives.

Every day, the women not only repost different versions of Morgan’s missing person’s flyer — including one created by the Black and Missing Foundation — they comb through apps such as Ring and a premium version of Citizen to post Morgan’s flyer and follow potential leads.

Riley, 35, hasn’t met Morgan yet, but has been heartened by how many people the missing woman is connected to. Morgan’s former dance classmate and friends from church have sent Riley private and public messages of encouragement and reposted the flyer.

“I’m just like, wow, like, she is connected to people and I don’t know if she’s aware of it. You know what I mean?” Riley said, referring to the loneliness Morgan may be experiencing because of her mental health.

If anything, it has been Morgan’s family, friends, and people from her school community who have reached out and are looking for her, Wade said. The women collectively feel like everybody’s looking for Morgan except the police.

“I’ve gotten in my car and drove to areas where people said they saw her, and I’ve driven around looking in those areas,” Snowden, 39, said. “This is somebody who has been missing, unaccounted for. … Anybody who is a decent person, who is a Christian, who is just concerned about other people in general, will think that it is imperative that we do everything we can to help this family.”

As of April 15, Farley said he hadn’t heard from a case detective, and Morgan’s missing person flyer was not published on the police department’s website or social media accounts.

A spokesperson with the police department confirmed in an email to Capital B on April 16 that Farley did file a missing person report, but “detectives need permission from family members to share this information publicly.” Farley submitted the report in person; it’s not clear who else would have given permission to publish Morgan’s missing person information after the report was submitted by her father.

“The police never said to us, ‘Do we have your permission to post this online?’ I assume all of the missing person flyers will be posted online,” Wade said.

That same day, Farley received a call from a detective, and the flyer was published on the police department’s website.

“She was smiling”

“The frustration is we don’t know if she’s by herself. We don’t know if she is safe. We don’t know if she’s with someone who’s putting her in danger. We don’t know if she does not want to be found,” Wade said. “It’s just a very frustrating situation where you don’t really know what you’re looking for or what to expect.”

In the days leading up to Morgan’s disappearance, she was in good spirits for the first time in a long time, Farley recalled. Morgan has struggled throughout her life and never really got over their mother’s untimely death in 2007.

“I’m not sure she fully recovered from losing a parent at that young of an age,” Wade said. Morgan was 8 and Wade was 20 when their mother died.

As a single parent, Farley’s father-daughter bond has been a work in progress, especially since she moved back home in 2022. At the time, Morgan had been managing trust issues following the end of some unhealthy relationships. That same year, her paternal grandparents died on the same day.

About a year ago, Morgan experienced her first known mental health crisis, for which Farley had her committed to a psychiatric hospital. There, Morgan was diagnosed with depression.

Keeping up with appointments and taking her medications had been a challenge for Morgan, but “she had actually been getting better,” Farley said. “We were communicating better. She was smiling.”

For months, it had been difficult for Farley to hold back his tongue from providing any parental advice to his adult daughter, so he followed in his mother’s footsteps and started writing Morgan letters.

To keep the peace inside of Farley’s childhood home, his mother used to write him letters. It wasn’t until after she died that he said he could fully digest his mother’s wisdom written on those sheets of paper. For the better half of April, Farley has found himself writing letters to Morgan, that includes prayers for her safe return home.

The post So Many Are Searching for This Missing Black Woman — But Not Chicago Police appeared first on Capital B News.