The Coffer Illusion Happened Largely By Accident

“Hearst Magazines and Verizon Media may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

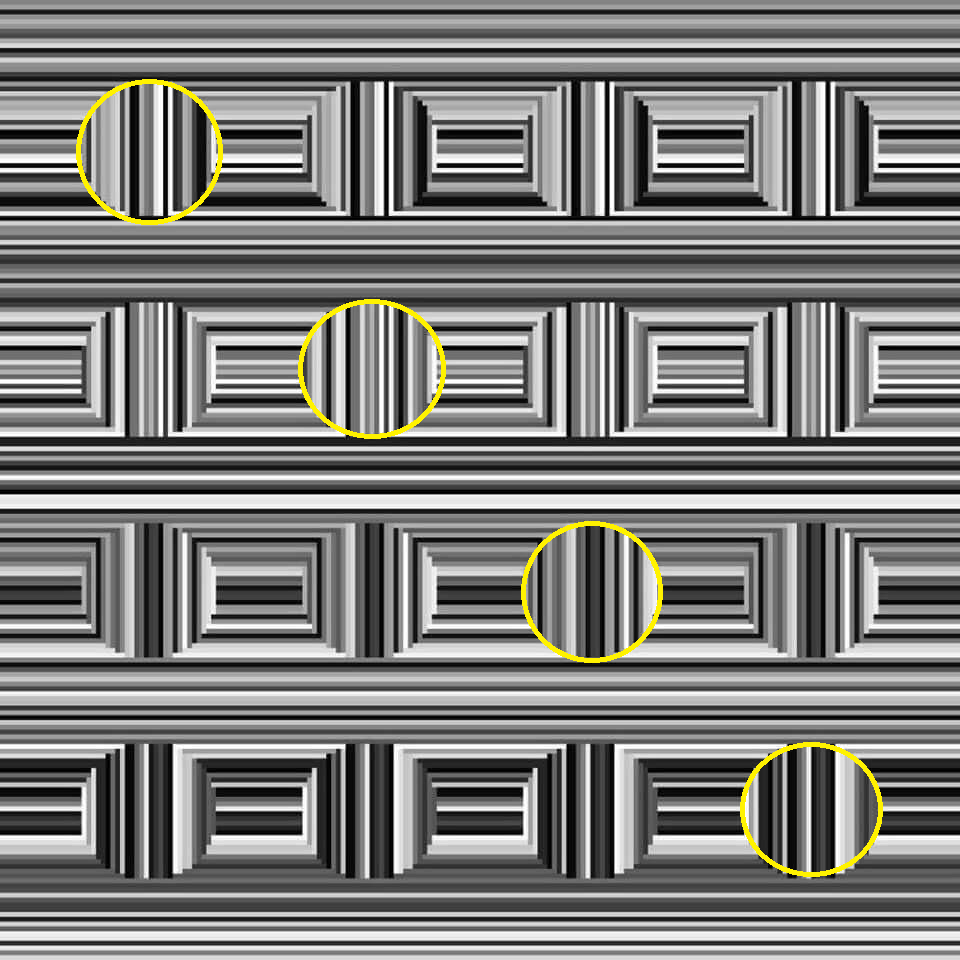

Take a long, hard look at the image above. What do you see?

If you’re like most people, you easily spot 20 squares, or more specifically, coffers—those decorative, rectangular figures full of sunken panels that you usually find on ceilings and soffits. When we conducted a poll of Popular Mechanics readers on our Instagram, for example, 857 people in a pool of 966 said they saw squares.

But that still leaves the 109 readers who are part of the chunk of the population that sees the other shape in this picture whenever it goes viral. (And it does, often.) When the image made waves once again last week, some people said they immediately saw the 16 circles hidden in plain sight. Black magic f***ery, indeed.

What we have here is the Coffer Illusion, a now-classic visual trick that debuted as a finalist in the 2006 Best Illusion of the Year Contest, in which the Neural Correlate Society (NCS)—a nonprofit that spreads the awareness of new cognitive research—highlights especially trippy perceptual experiences from the world’s foremost illusion artists.

Though the Coffer Illusion didn’t snag that year’s top prize, it’s had a longer shelf life than any of the other finalists, including the winner. Not bad for an illusion that happened largely by accident. “It was a serendipitous discovery,” says Anthony Norcia, the guy who discovered it.

“We were developing stimuli for experiments on figure ground segmentation based on orientation cues,” Norcia, a psychology professor at Stanford University, tells Popular Mechanics. “The idea was that we would record brain waves while participants watched displays that alternated between a uniform field of bars and images that had circles defined by orientation differences. Once [my programmer] had the display ready, I looked and noticed the illusion.”

At its root, the Coffer Illusion is an illusion that involves ambiguous stimuli with more than one interpretation, says Norcia. It bombards your visual system with information that you can resolve in multiple ways.

Think about a classic illusion like Rubin’s Vase, where your perception repeatedly toggles between a vase and a silhouette with two faces; last year’s controversial video of a raven that sure looks like a rabbit; or The Dress, where your brain either sees a garment that’s black and blue or one that’s white and gold, and dammit, you’ll fight anyone who sees the opposite.

But the Dress split the world into two factions when it exploded five years ago because its stimuli “have strong individual differences in the preference for which interpretation is made first,” Norcia says. That’s not quite the case with the Coffer. In his illusion, “the overwhelming majority of people see the coffer and not the circle interpretation when they first see the image.” You have to do a little more legwork to find the second.

So why, then, do most people see squares right off the bat? In 2017, Susana Martinez-Conde, Ph.D., director of the Laboratory of Integrative Neuroscience at SUNY Downstate Medical Center (and the mind behind the Best Illusion of the Year Contest), wrote about Norcia’s enduring work in her book, Champions of Illusion:

Our brains preferentially extract, emphasize, and process these unique components that are critical to identifying an object. Sharp discontinuities in the contours of an object, such as corners, are less redundant—and therefore more critical to vision–because they contain more information than straight curves.

Basically, Martinez-Conde tells Popular Mechanics, “we’re preoccupied with corners and angles.” In her work, she’s found that with the exact same level of physical luminance, a corner is going to look brighter than a straight edge or the soft curve of a circle. “So the perceptual result” of the Coffer Illusion, she says, “is that corners are more salient than non-corners.”

Plus, we may just see more rectangular shapes than we do circles, says Kyle Mathewson, Ph.D., a neuroscientist in the psychology department at the University of Alberta. (Think: computer screens, signs, and buildings.) “What we see when we look around the world is influenced heavily by what we have already seen in our past,” he tells Popular Mechanics.

But our past may also explain why some people see the 16 circles in the Coffer Illusion right away. “Once you know the circles are there,” says Martinez-Conde, “you can see this illusion again weeks, months, or even years from now, and you’re not going to have trouble seeing the circles.”

Since the Coffer Illusion is 14 years old, it’s possible you were exposed to it a long time ago and forgot about it, but still remembered the circles were there when you saw it again, she says. She points to a well-known picture in which a Dalmatian is hard to notice at first, but once you see a hint that indicates where the dog is, it’s impossible not to see it going forward.

You can prompt someone to see the circles in the Coffer Illusion in several ways. Like the Dalmatian example, you can superimpose dotted lines where the circles are supposed to go, and then turn them off. Norcia, meanwhile, uses a laser pointer to outline the circular boundaries for large crowds. “There’s an audible ripple through the audience as the aha moment occurs,” he says.

And then there’s one last bit of trickery: priming people with a language cue. Remember the raven that looked like a rabbit? The original tweet that set off the debate was captioned, “Rabbits love getting stroked on their nose,” which led some people to interpret the image as a rabbit.

Rabbits love getting stroked on their nose pic.twitter.com/aYOZGAY6kP

— Dan Quintana (@dsquintana) August 18, 2019

You can use the same strategy with the Coffer Illusion—and we did.

“A good experiment would be to ask naive viewers to tell you either ‘how many circles’ or ‘how many squares’ they see,” says Mathewson. “I’d predict those asked how many circles would be more likely to endorse perceiving the circles from the start.”

So if you clicked on this story with the headline, “How Many Circles Do You See Here?” and frantically searched the image for spheres, then our ruse worked. Glad we could help.

You Might Also Like