A Man Killed Frank Lloyd Wright’s Lover And 6 Others. A Century Later, No One Knows Why.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright was not at home when a hatchet-wielding employee murdered seven people and set fire to the Wisconsin house that Wright had built for the woman he loved.

She was the killer’s first victim.

Wright, then 47, lived for another four decades after the tragedy, and the mass murder remains a nearly forgotten chapter of his life.

But headlines at the time screamed about the bloodshed at Wright’s “Love Cottage” — so dubbed by scandal-hungry newspapers because Wright had left his wife and six children and built the Wisconsin home to live with Martha “Mamah” Borthwick. The two had met through her husband, Edwin Cheney, who’d commissioned Wright to design a house for his family.

Wright and Borthwick began an affair and lived together for a period in Europe. The Cheneys got a divorce, but Wright’s wife, Catherine Lee Tobin, refused to grant him one. So Wright and Borthwick moved to Spring Green, Wisconsin, to live openly as a couple far from the disapproving Chicagoans who were scandalized by their relationship.

The innovative architect was known for bucking convention as much as for his architecture. He would go on to design the spiraling Guggenheim Museum in New York, and was already famous at the time for his Midwest “prairie”-style homes fitted with stained-glass windows and the unique integration of “form and function” in his designs.

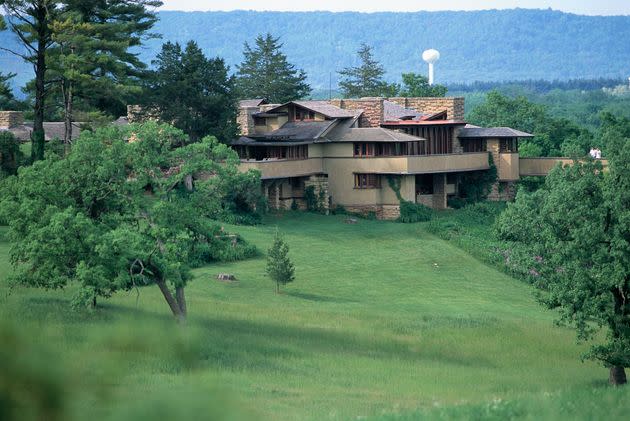

Wright designed and built the Wisconsin house and a studio in 1911. He called the estate Taliesin, a Welsh name meaning “shining brow,” a reference to its location in the “brow” of a hillside. It was about 180 miles northwest of Chicago, Wright’s original base, where he was working on Aug. 15, 1914, the day of the killings.

The victims

It was warm that Saturday at Taliesin, and Borthwick lunched outside on a terrace with her children, 8-year-old Martha and 11-year-old John. The siblings lived full-time with Cheney, their father, but they were staying at Taliesin while he was away on a business trip.

Meanwhile, four men who worked for Wright and also lodged at the estate ― draftsmen Emil Brodelle and Herbert Fritz, handyman and foreman Thomas Brunker and gardener David Lindblom ― were in the dining room inside. They were joined by carpenter Billy Weston, whose 13-year-old son, Ernest, accompanied him to work every day.

They were dining on soup ladled into their bowls by their killer. None of them had heard the screams that had just sounded from the terrace outside.

Only Fritz and Billy Weston survived the events of that day.

The killings

The killer was Julian Carlton, a 30-year-old man described variously as a chef, cook, butler and/or handyman on the property. His wife, Gertrude, also worked at Taliesin, and he told her to leave the property before he picked up his weapon.

Mamah Borthwick was his first victim. Carlton, standing behind her, swung his hand ax — also called a slinging hatchet — with such force that the blade nearly cleaved her head in half. Her son John was reportedly killed next, in the same way. They both died instantly, but Borthwick’s daughter Martha initially survived the attack. She ran from Carlton, who gave chase. When he caught up, he sliced Martha three times in the back of the head and hit her so hard with the ax’s hammer-like handle that her face caved in.

While the men were eating, Carlton poured gasoline under the dining room door, lit a match and ran outside.

Fritz, already badly burned, was the first to escape, breaking his arm as he broke through a window. As he rolled down a steep hillside toward the water, he saw Carlton approach the broken window where Brodelle was now trying to flee the flames.

As Brodelle fell, Carlton buried the ax in his head.

He then struck the elder Weston, who had managed with the others to break down the dining room door as fire engulfed the room, but the blows weren’t fatal.

When the others emerged, they were burned so badly that they might not have survived anyway. Still, Carlton struck them, one by one, with the ax.

Before he fled the scene, Carlton returned to the terrace, where he poured gasoline on Borthwick and her son’s bodies and set them on fire.

Miraculously, Lindblom and Brunker survived for another two days. Two of the children, Ernest and Martha, hung on for another few hours. Martha had managed to crawl to the courtyard, where rescuers found her gasping, her clothes burned off from the fire Carlton set. Ernest died at about the same time.

Carlton was Black, and Wright biographer Paul Hendrickson later wrote that according to an oral history, as Billy Weston’s son lay dying, Weston identified their attacker as “that n****r up there.”

Possible motives

Carlton’s race dominated headlines and was a lightning rod for local outrage. (A gathering group of people threatened to lynch Carlton before the sheriff intervened.) It even received a mention in the official cause of death for three victims ― “killed by a Negro,” as William Drennan wrote in his 2007 book, “Death in a Prairie House.” Carlton said he came from Barbados, but he may have originally moved to the Midwest from Alabama, as Hendrickson theorized in his 2019 book, “Plagued by Fire.”

The motive for the massacre is still unclear. The killer himself may not have known. In any case, he did not — or perhaps physically could not — explain it to police before he died seven weeks later.

Although nearly two-thirds of the Taliesin house was destroyed in the fire, the flames didn’t reach Carlton — nor did what was reportedly a gathering lynch mob.

When he was found hiding in a boiler below the house at 5:30 p.m. the day of the killings, Carlton had swallowed muriatic, or hydrochloric, acid. It ravaged his esophagus, and according to some reports (disputed by Hendrickson and Drennan), he could not even eat or drink, much less speak. His eventual cause of death was listed as starvation.

Both among historians and in contemporary reporting, retaliation for a racist confrontation is one of several popular theories put forth to explain Carlton’s murderous rampage. Several days before the massacre, Carlton was reportedly humiliated when Brodelle called him a “Black son of a bitch” — perhaps a sanitized reporting of a racial slur — after Carlton refused his order to saddle his horse.

Vengeance for another reason has also been suggested: Aug. 15 was the Carltons’ last day of work at Taliesin. Whether Carlton was fired or chose to depart is unknown, but historians have found evidence that the couple may have already planned to leave.

In a blog post about the fire, Wright historian Keiran Murphy casts doubt on other possible scenarios: that Wright had hired someone to kill Borthwick, that it was a mob hit, or that Carlton was so scandalized by Wright’s extramarital relationship that he was acting as a sort of avenging angel.

Historians like Drennan and Hendrickson believe that while the confrontation with Brodelle might have been a precipitating factor in the murders, Carlton — who had previously shown signs of paranoia — was more likely suffering from some kind of mental illness or breakdown.

Murphy quoted the architect’s words from his autobiography about his decision to rebuild Taliesin after the fire, once his rage “began to fade away.”

“[I] finally took refuge in the idea that Taliesin should live to show something more for its mortal sacrifice than a charred and terrible ruin on a lonely hillside in the beloved Valley,” Wright said.

Remarkably, Taliesin’s living quarters burned down a second time, in 1925. This time, arson was ruled out — investigators attributed the blaze to faulty telephone wiring — and no one was hurt. Wright rebuilt it again.