Man behind the ballot: How a Democrat changes laws in a Republican state

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

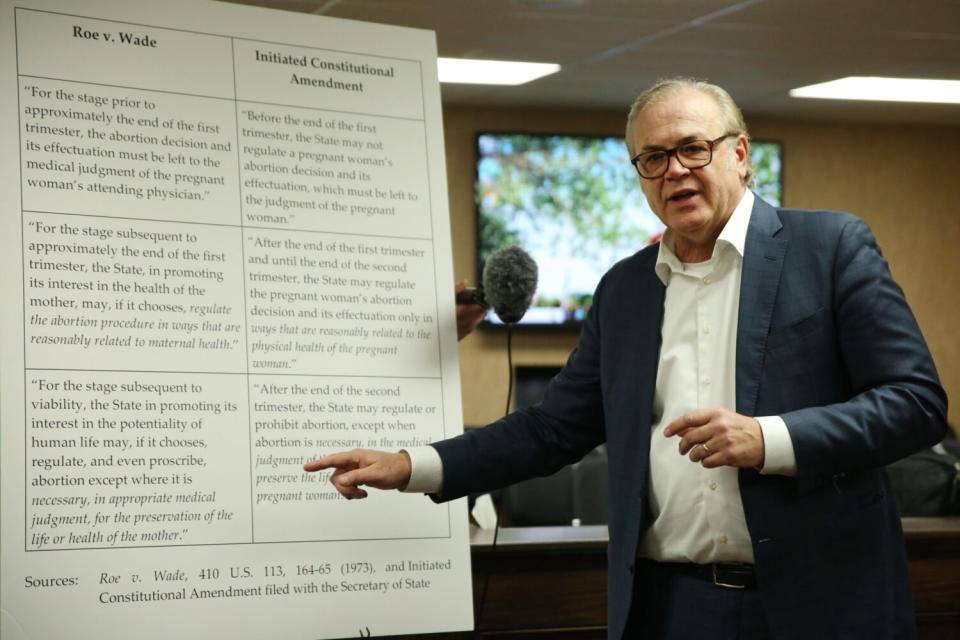

Rick Weiland of Dakotans for Health speaks to the press Feb. 7, 2024, at the South Dakota Capitol in Pierre about an initiated constitutional amendment to re-establish abortion rights in the state constitution. (Makenzie Huber/South Dakota Searchlight)

Since 2014, South Dakotans have voted for ideas including a higher minimum wage, stricter anti-corruption laws and expanded Medicaid eligibility. This November, statewide ballots are likely to include measures that would restore abortion rights and repeal the state sales tax on groceries.

One Democratic former candidate for Congress has played a part in all of it.

After three unsuccessful runs for office, Rick Weiland knows the grim prospects for Democrats in South Dakota. Republicans hold every statewide office and all but 11 of 105 seats in the Legislature. So, instead of pursuing his own electoral ambitions further, he pivoted toward ballot measures to influence public policy.

“The focus is on issues that resonate broadly with South Dakotans, irrespective of party affiliation,” Weiland said.

Ballot question committees chaired by Weiland have raised more than $3 million since 2014. He’s led or participated in 11 measures. Five were approved by voters, three are pending for this year’s ballot, two failed to make the ballot and one was rejected by voters.

Weiland’s strategic shift to ballot measures is rooted in his belief that some progressive policies, presented directly to voters, can transcend the Republican vs. Democrat divide.

“When the policy is removed from all that party stigma, people think with their brains,” Weiland said.

Weiland’s work at the ballot

Ballot campaigns led by Rick Weiland or his organization:

Increasing government transparency/campaign finance reform, 2016: approved by voters 52%-48%, but later gutted by the Legislature.

Requiring the state to negotiate drug prices with drug companies, 2018: failed to make the ballot.

Reinstate abortion rights, 2024: petitions submitted, pending verification of signatures.

Repeal the state sales tax on groceries, 2024: petitions submitted, pending verification of signatures.

Ballot campaigns that Rick Weiland or his organization assisted with:

Minimum wage increase tied to inflation, 2014: approved by voters 55%-45%.

Referendum to overturn legislative reduction of the youth minimum wage, 2016: approved by voters 71%-29%.

Nonpartisan primary elections, 2016: rejected by voters 55%-45%.

Cap the interest rate of payday loans, 2016: approved by voters 76%-24%.

Repeal a single-subject requirement for ballot questions, and amend the process, 2020: failed to make the ballot.

Medicaid eligibility expansion, 2022: approved by voters 56%-44%.

Nonpartisan primary elections, 2024: petitions submitted, pending verification of signatures.

Influenced by the ’60s

Weiland, 65, was born and raised in Madison. His parents, Thoreen and Donald, owned and managed a funeral home and ambulance service.

Growing up during the civil rights movement, anti-Vietnam War protests and the push for gender equality, Weiland said he was exposed to activism and political engagement daily.

“My family would debate the Vietnam War around the dinner table,” he said.

Moments like that planted the seeds of a future career.

“It also didn’t hurt that my parents were involved with George McGovern’s campaign,” Weiland said, referring to the former U.S. senator for South Dakota and the Democratic Party’s 1972 presidential nominee.

Weiland’s journey into public service began as he completed his studies at the University of South Dakota in 1980. He became a staffer for then-Congressman Tom Daschle, a Democrat who was running for reelection.

Weiland rose through the ranks to become a national finance director and senior adviser for Daschle.

“He did a phenomenal job at that,” Daschle said. “I don’t know anybody that works harder than Rick does.”

Daschle was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1986 and eventually served stints as Senate minority leader and majority leader.

Weiland returned to South Dakota as Daschle’s state director in 1989. His work for Daschle spanned 20 years.

Running for office

Weiland became the Democratic nominee for South Dakota’s lone congressional seat in 1996.

“I had been in the political trenches,” Weiland said. “I had a good understanding of the process and our state. The timing seemed right.”

He lost the general election to Republican John Thune, who later ousted Daschle from the Senate in 2004.

“It was becoming tough for Democrats,” Weiland said.

He made another run for the congressional seat in 2002. He lost in the primary election to fellow Democrat Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, who ultimately served in the House from 2004 to 2011. She was defeated in the 2010 election by now-Gov. Kristi Noem, a Republican.

Meanwhile, Weiland served under President Bill Clinton as a regional director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, guiding recovery efforts after the 1998 tornado in Spencer, South Dakota, and providing public affairs support after the 1999 Columbine school shooting in Colorado.

“I started with the Grand Forks flood in North Dakota,” Weiland said. “It was unbelievable.”

Weiland later led the International Code Council as CEO and helped to create the nation’s first Green Construction Code in 2012, “marking a substantial step toward sustainable building practices,” he said. The council creates codes to ensure buildings are safe, sustainable and accessible.

“We developed a culture around being good stewards of the planet,” Weiland said.

In 2014, South Dakota Democrat Tim Johnson announced he would retire from the U.S. Senate rather than seek reelection. Weiland earned the Democratic nomination for the seat but lost the general election to Republican former governor Mike Rounds, in a race that also included former Republican U.S. Sen. Larry Pressler running as an independent.

An ad from Rick Weiland’s 2014 U.S. Senate campaign.

Pete Stavrianos worked on the staffs or campaigns of prominent South Dakota Democrats including Democratic U.S. Senators McGovern, Jim Abourezk, Daschle and Johnson. Stavrianos worked alongside Weiland and advised his campaigns.

“Rick was a more polished candidate than Daschle when Daschle first started,” Stavrianos said. “He would have easily been elected in 1986. But, you know, times were changing.”

Over the prior three decades leading up to Weiland’s 2014 race, Stavrianos said more rural Americans began blaming the government for the nation’s problems, “rather than powerful corporate interests, like in the Roosevelt era — railroads, mining companies, you know, the people controlling their government, not ‘the government.’”

“When politicians and government are not respected by the public, the people arguing for ‘less government’ do better,” he said. “We were so focused on winning elections, we missed that we were losing the broader narrative.”

Daschle said politics was formerly local, but “I don’t think that’s as true anymore.” He pointed to the public’s shift from reading local journalism toward watching national news commentary as an example.

However, Daschle said, “I think the people of South Dakota still have the right sense of the issues,” and he said that’s why progressive ballot measures still pass in the state.

Weiland had become well aware of those insights by the end of the 2014 election. It was also during that campaign that he found an alternative path to pursue the policies he favored.

A new approach

Alongside Weiland’s 2014 Senate race was a ballot measure asking South Dakota voters to raise the minimum wage.

“Getting that on the ballot and passed was part of my stump speech for the Senate,” Weiland said. “It wasn’t my bill, but when we were collecting signatures to get me on the ballot, we’d collect signatures for minimum wage as well.”

Voters approved the measure, raising the minimum wage from $7.25 to $8.50 and increasing it each year based on inflation.

“I think passing that really pissed the Republican Party off,” Weiland said.

During the next legislative session, the Republican-controlled Legislature passed a bill decreasing the minimum wage for workers under age 18 from $8.50 to $7.50. Weiland helped gather petition signatures to refer that legislation to the 2016 ballot, and voters rejected it.

The 2014 and 2016 minimum wage wins solidified a belief for Weiland.

“What it showed me was that people care more about issues than they care about political parties,” he said.

People care more about issues than they care about political parties.

– Rick Weiland

Weiland and a small team decided to propose ballot measures of their own.

He co-founded TakeItBack.org, the website for a political nonprofit and political action committee, with Drey Samuelson, a former Daschle staffer and former chief of staff for Sen. Johnson. The group organizes ballot measures and ballot question committees.

“We believed the way to reform the political process in South Dakota was through the ballot measure process,” Samuelson said. “The political divide is such that people are unwilling to cross the partisan line, but they will vote for policies they agree with.”

Samuelson said he was highly involved in the organization’s early years but turned over the reins to Weiland and Weiland’s son, Adam Weiland, around 2020 to focus on other matters.

“I’m proud of what Rick has accomplished,” said Samuelson, who is helping with this year’s ballot question asking voters to implement open primary elections. Weiland is not leading that effort but has assisted with it.

Weiland said Take it Back has five employees, including himself and Adam, plus contracts with dozens of people. It also works with volunteers.

State law dictates the number of petition signatures required from registered voters to place a measure on the ballot. This year, the requirements are 17,508 signatures for an initiated measure or referred law, and 35,017 for an initiated constitutional amendment. Given the number of signatures needed, ballot question committees often hire people to circulate petitions.

Money comes from donors across the state and nation. Weiland and his team are paid from those donations.

“It’s not paying the bills, let’s just say that,” said Weiland, who owns multiple restaurants in Sioux Falls. He declined to go into further specifics about Take It Back’s payroll.

On the heels of scandal

Beginning in 2013 and continuing for several years, South Dakota faced two major scandals, known by the names EB-5 and GEAR UP.

The EB-5 scandal — named for a type of visa given to foreign investors — involved the alleged misuse of public funds by a former state official who committed suicide before being criminally charged.

GEAR UP — the name of a program intended to help prepare Native Americans for college — involved the alleged misuse of public funds by a man who ultimately killed himself, his wife and four children.

In response to public calls for corruption reforms, Weiland’s team introduced two ballot measures, including one for nonpartisan primary elections, which voters rejected. The effort raised $1.63 million, the biggest donor being Open Primaries of New York. It’s a nonprofit hoping to enact open primaries in all 50 states.

The other measure was Initiated Measure 22. It aimed to reduce corruption and increase government transparency. It passed but was later mostly repealed by the Republican-controlled Legislature.

The committees created for Initiated Measure 22 – South Dakotans for Ethics Reform and South Dakotans for Integrity – raised a combined $1.66 million. The top donor was a Massachusetts-based nonprofit focused on campaign finance reform, Represent Us, that gave $1.05 million.

Weiland also assisted with a successful measure in 2016 to cap the interest rate of payday loans at 36%. The industry fled the state upon the bill’s passage.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

In 2018, Weiland worked with former Democratic U.S. Senate candidate Clara Hart to propose a ballot question requiring the state to negotiate drug prices with drug companies, similar to the way the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs does.

Opponents of the measure sued and found enough problems with the petition signatures and the circulation process to invalidate the measure and remove it from the ballot.

In 2020, Weiland helped with a ballot measure to repeal the single-subject requirement for ballot questions, change the deadline for turning in petition signatures, and change other requirements for initiatives and referendums to remove obstacles standing in the way of placing measures on the ballot. Proponents did not gather enough signatures and the measure did not make the ballot.

In 2022, Weiland and Take It Back created a ballot question committee, Dakotans for Health, which pushed for Medicaid expansion.

The group received enough signatures and raised $528,410 but withdrew its measure from the November 2022 ballot. It instead aligned with South Dakotans Decide Healthcare to support its separate and ultimately successful Medicaid expansion measure. That measure already had support from the state’s hospitals.

“Without Rick and Farmers Union pushing it, I don’t think it would have gotten done,” said Mitch Richter, who lobbied for the ballot measure that ultimately passed. “You need someone like Rick if you want to get the job done. Anymore, it costs about $1 million just to get an issue on the ballot.”

Critics of Weiland’s approach

In 2022, there was also an unsuccessful ballot measure to legalize recreational marijuana supported by a group led by Matthew Schweich. He said Dakotans for Health reached out to help get signatures for the measure.

“Marijuana was galvanizing a lot more voters than Medicaid,” Schweich said. “So, by carrying both, they could get more signatures. And they collected a good number of signatures for us.”

However, Schweich said, “I don’t see myself working with them again.”

He said what started as Weiland’s team voluntarily helping to collect signatures turned into an expectation of payment. Weiland confirmed that, saying, “Yeah, we thought we should be paid for our work.”

Meanwhile, others take issue with ballot measure tactics more broadly.

Joel Rosenthal, a former chairman of the state Republican Party, said that while paying people to circulate petitions is a legitimate campaign practice, it can mislead the public into believing there is more support for a cause than there is.

“They’re using ballot initiatives to do what they can’t do in the Legislature,” he said.

Rosenthal thinks increasing signature requirements for ballot measures “would update our laws to reflect the intent of what the initiated measure process was created for.”

“When this was created in the 19th century, out-of-state donors couldn’t just pay people to stand outside the mall and collect signatures,” he said.

Drey Samuelson said Republicans need to look in the mirror.

“If they want to talk about limiting money in politics, I’m happy to listen,” he said. “They don’t mind it when it serves their interests.”

Rosenthal also said if Democrats want to enact laws, they should get elected to the Legislature and introduce them in Pierre.

“There, a bill has to pass committees, the House and Senate, and then the governor,” he said. “That means the bill gets vetted along each step of the way. I believe in democracy, and that our vetting system is superior to television advertising and one-liners.”

Weiland does not agree that lawmaking should be the exclusive domain of lawmakers.

“Yeah, sure, the lawmakers, along with all the special interests and their pockets full of money,” Weiland said. “If they’re doing their jobs, listening to what the people they represent want, I wouldn’t be here. We’re doing their job.”

Weiland said ballot measures are vetted by the Legislative Research Council, the attorney general and ultimately the voters. The Legislative Research Council looks at the proposed idea to check how it might affect the state’s laws and budget. It advises on how to write the proposal. After that, the Attorney General’s Office steps in to write a title and ballot explanation.

Like a ‘musket against an AR-15’

Pete Stavrianos, the Democratic former longtime politico and congressional staffer, thinks Republicans in the Legislature are overreacting to the handful of wins progressives have achieved through the ballot measure process.

“Ballot measures are like fighting with a single-loader musket against an AR-15,” he said. “If you care about making a difference and they’re the only available option, then you do it.”

This year, Weiland and his team have put two more measures on the ballot: removing the state sales tax on groceries and restoring abortion rights.

“Stuff that affects everyone’s lives,” Weiland said.

Dakotans for Health Executive Director Rick Weiland speaks to the press Feb. 7, 2024, at the Capitol in Pierre about an initiated constitutional amendment to enshrine abortion rights in the state constitution. (Makenzie Huber/South Dakota Searchlight)

The abortion rights petition motivated an anti-abortion response effort, asking voters to “Decline to Sign” the petition. That failed, and Weiland’s group collected more than enough signatures. But the Legislature passed a law last winter allowing petition signers to withdraw their signatures, and anti-abortion advocates are now coordinating a signature-withdrawal effort.

The measure would legalize abortions in the first trimester of pregnancy but allow the state to impose limited regulations in the second trimester and a ban in the third trimester, with exceptions for the life and health of the mother.

Weiland anticipates that if the measure passes, Republicans will “try to encroach upon the rights we have restored, and the bill will end up in the courts, and it’ll be challenged.”

Rep. Tony Venhuizen, R-Sioux Falls, opposes the ballot measure. He described Weiland as opportunistic.

“It’s pretty evident that Weiland gravitates toward measures that have deep pockets to pay for them, usually from out of state,” he said. Venhuizen sponsored a bill that will have voters deciding on another issue this November, asking if the state should be allowed to impose work requirements on Medicaid expansion enrollees.

While some of Weiland’s ballot measure campaigns include a big donor from out-of-state, not all of his efforts do. Dakotans for Health’s latest financial disclosure showed 379 people – mostly South Dakotans – made donations of more than $100 apiece, totaling $119,706 for an average of $316. Another $10,297 came from donors giving less than $100 apiece.

The biggest donation to Dakotans for Health was $55,000 from Take It Back, the other group Weiland helped found. Its latest filing shows $33,845 donated by individuals giving less than $100. Another 112 people from all over the U.S. donated more than $100, totaling $23,559.

Dakotans for Health spent about $249,000 last year, including about $44,000 toward salaries and $167,000 on consulting. Unlike some other states, South Dakota’s campaign finance laws and rules allow generic disclosures such as “consulting” without specific information revealing who was paid and for what.

Venhuizen is additionally critical of Weiland’s approach to the language of ballot measures.

“It’s also been clear that good drafting and public input are not high priorities,” Venhuizen said.

Venhuizen pointed to the Legislature’s repeal of most of the 2016 anti-corruption measure, Dakotans for Health’s Medicaid expansion proposal being shelved in favor of a similar measure, and this year’s measure to legalize abortion not receiving support from groups including Planned Parenthood and the American Civil Liberties Union.

Venhuizen alleged that Weiland wants to be the first to the ballot measure starting line, to be in a better position to raise money.

“I’ve helped on at least a dozen ballot measures and I’ve never been paid a dime,” Venhuizen said. “Most people who get involved in these things are volunteers. It’s not a business model.”

Weiland said Republicans attack his process because they know South Dakotans agree with his proposals. Since a U.S. Supreme Court decision triggered South Dakota’s abortion ban, Weiland noted, Republicans had the past two legislative sessions to implement “even the most basic rape and incest abortion exceptions – something even presidential candidate Donald Trump supports – but refused to. So, here we are.”

“You know,” Weiland added, “there really wouldn’t be a need for organizations like ours if the Legislature was doing its job and listening more to the people of our state and less to the organized special interests.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story has been updated since its original publication to correctly state the number of Democratic-held seats in the Legislature.

The post Man behind the ballot: How a Democrat changes laws in a Republican state appeared first on South Dakota Searchlight.