Before making eclipse history, this astronomer documented Cincinnati in the 1700s

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

If you saw the total solar eclipse earlier this month, you might have noticed what they call the diamond ring effect just before totality. The last rays of sunlight peeked through the mountains of the moon, creating beads of light. The final couple beads appeared as shining diamonds on a bright ring around the moon’s silhouette.

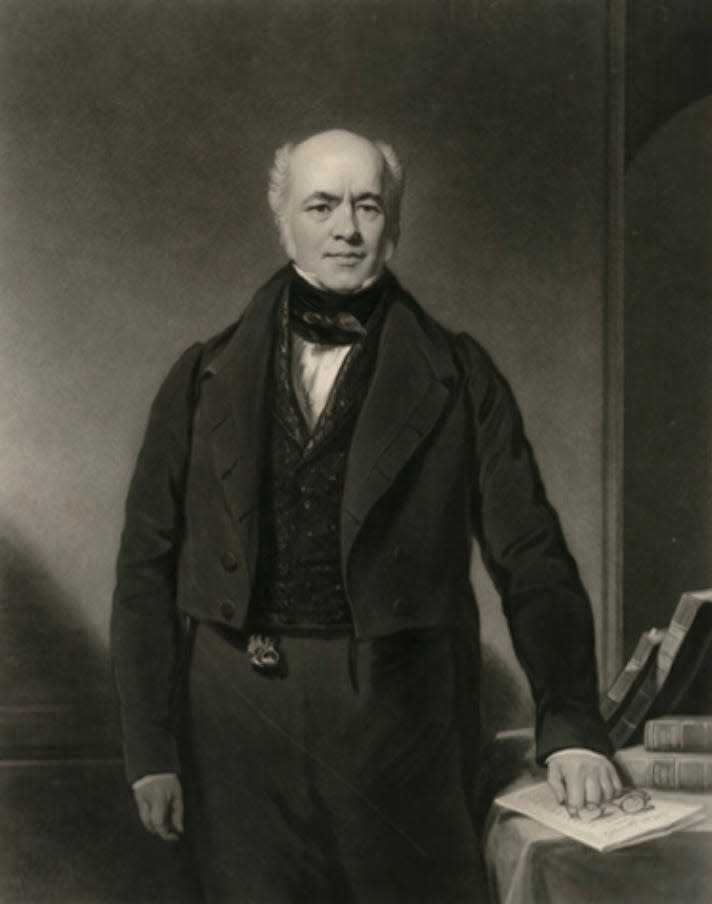

Those are known as Baily’s beads, named after English astronomer Francis Baily, who first observed the phenomenon during a total eclipse of the sun May 15, 1836. His vivid descriptions of the effect led to the popularity of the next eclipse in 1842.

Baily, born in Berkshire, England, in 1774, was one of the founders of the Royal Astronomical Society and served as president.

What does he have to do with Cincinnati history, you ask?

Well, when he was 21 years old, Baily set off on a two-year tour of North America during the early years of the United States, including stops in Cincinnati and through Kentucky country.

In 1856, several years after Baily’s death in 1844, his writings about the trek were published by Augustus De Morgan under the title, “Journal of a Tour in Unsettled Parts of North America in 1796 & 1797.”

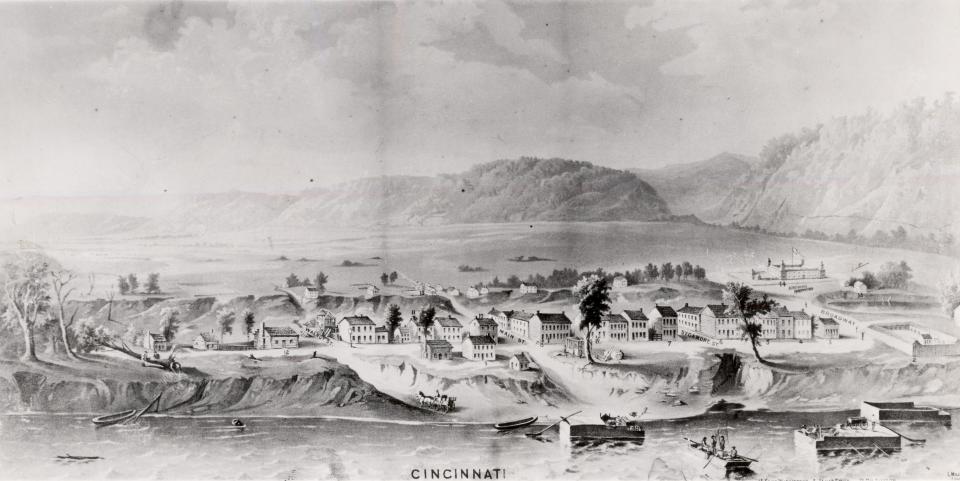

At the time of Baily’s visit, Cincinnati was less than a decade old, founded in December 1788. Most of the surrounding territory was wilderness. Cincinnati was part of the Northwest Territory, before Ohio was admitted to the Union in 1803.

Travel was difficult in the early days of the United States

Baily embarked on a journey to America on Oct. 21, 1795. After several months at sea, he made it to Norfolk, Virginia. Over the next two years he traveled throughout the United States (there were just 16 states in 1796) and much of the western country.

He visited the established Eastern cities Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York, where he found some places still showed the scars of battle from the Revolutionary War.

He headed west on Sept. 1, 1796, starting at the new city of Washington, D.C., founded just a few years earlier in 1790.

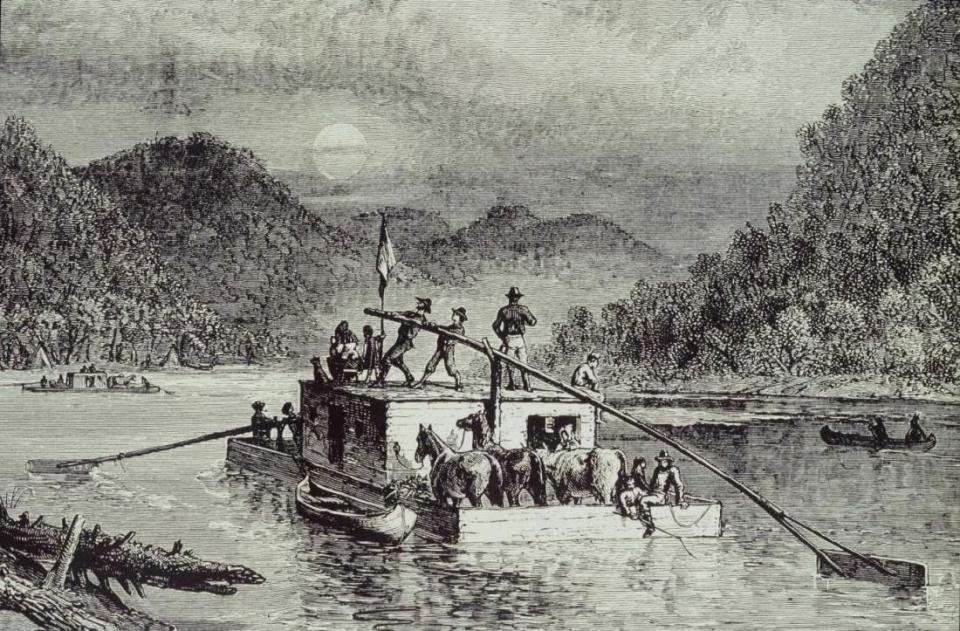

Travel in the late 18th century was arduous and slow. There were no freeways, no railroads, no canals. Roads were unpaved. Riverboats were powered by oars, not steam yet.

In the Eastern states, travel between cities was by coach. Roads were “agreeable” in the summer but had great difficulties in the winter.

Travel in the western frontier was by wagons and horseback over the Appalachian Mountains until they reached the Ohio River. But the river was frozen in the winter months, and they had to camp out in the small settlements for weeks at a time.

Cincinnati, the 'metropolis of the north-western territory'

Once the frozen river was broken up, they floated down on a newly constructed boat 13 feet wide and 40 feet long, boarded at the sides and covered at the top all the way except at front, which was left open for the horses and for the men to row.

On Feb. 27, 1797, the boat arrived at Columbia, which had preceded Cincinnati as a settlement by two months. (It is now Cincinnati’s Columbia Tusculum neighborhood.)

Columbia, Baily wrote, “was never in a very flourishing state; the neighbouring and well-settled country round and at Cincinnati, prevents it from being a place of any great importance; besides it lies very low, and is often overflowed from the river, which prevents any houses being built immediately on the banks, as is customary in these new settlements.”

Based on his observations of several frontier colonies, Baily described what he called the “first class” of settlers, the pioneers who purchase a tract of uncultivated land to start a new life: “a race of people rough in their manners, impatient of restraint, and of an independent spirit, who are taught to look upon all men as their equals, and no farther worthy of respect from them than their conduct deserves ... They are a race which delight much to live on the frontiers, where they can enjoy undisturbed, and free from the control of any laws, the blessings which nature has bestowed upon them.”

When the second class arrived, a little more refined, the first group typically sold their stakes and moved on to another frontier. It was not until the third class arrived that any kind of society emerged.

On April 3, Baily put his luggage in a canoe and rowed down river about six miles to Cincinnati.

He described Cincinnati of that time as “built partly on the bottom (near the river) and partly on the second bank,” the flatter basin area of Downtown.

“Cincinnati may contain about three or four hundred houses, mostly frame-built,” he wrote. “The inhabitants are chiefly employed in some way of business, of which there is a great deal here transacted, the town being (if I may so call it) the metropolis of the north-western territory. This is the grand depôt for the stores which come down for the forts established on the frontiers ...

“On the second bank, not far from the fort (Fort Washington), there are the remains of an old fortification with some mounds not far from it. It is of a circular form; and, by walking over it, I found the mean diameter to be 312 paces, or 780 feet, which makes the circumference very near half a mile.”

This was probably the ancient burial mound near Fifth Street that Dr. Daniel Drake described in his 1815 book, “Natural and Statistical View, or Picture of Cincinnati and the Miami Country.” That mound was obliterated by the development of Cincinnati. The site now contains Fountain Square and Carew Tower.

At Yeatman’s tavern, Baily met with Judge Jacob Burnet, who proffered an invitation to accompany him to New York and Niagara Falls. But Baily chose to continue toward New Orleans.

A chance encounter with Daniel Boone

While aboard a flatboat headed to Louisville, Baily’s group spotted a canoe on the river that pulled alongside them.

“It contained but one old man, accompanied by his dog and his gun, and a few things lying at the bottom of the canoe,” Baily wrote. “We called to him to come into our boat, which he accordingly did; and after a little conversation, our guest proved to be old Colonel Boon, the first discoverer of the now flourishing state of Kentucky. I was extremely happy in having an opportunity of conversing with the hero of so many adventures.”

Daniel Boone (the spelling of his name had not yet been formalized) was already a legend. His exploits were first published in the book “The Discovery, Settlement and Present State of Kentucke” by John Filson, one of Cincinnati’s founders. That account of his adventures was reprinted in a book by Gilbert Imlay, and Baily had a copy of that book with him.

“I read it over to (Boone), and he confirmed all that was there related of him,” Baily wrote. “I could observe the old man’s face brighten up at the mention of any of those transactions in which he had taken so active a part ...

“I was much pleased with the old man’s conversation, as he appeared to be one who had seen a great deal of the world, though in its most uncultivated state; nevertheless, being a man of strong natural parts, his observations on the different objects which had passed before him rendered the half hour he stopped with us very interesting and amusing.”

Baily’s journal writings of the tour were unpublished in his lifetime. De Morgan noted that if they had been published when written, they would have “made him a name among enterprising travellers, and might have changed his career” and enabled him to make further travels.

Instead, his path took him elsewhere – to the stars.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: What astronomer Francis Baily wrote about Cincinnati in the 1700s