Listen up, Louisville. Mattie Jones has advice for today's racial justice leaders.

Mattie Jones wants you to know that she may be done marching, but that doesn’t mean she’s finished helping. America's racial justice fight is not finished.

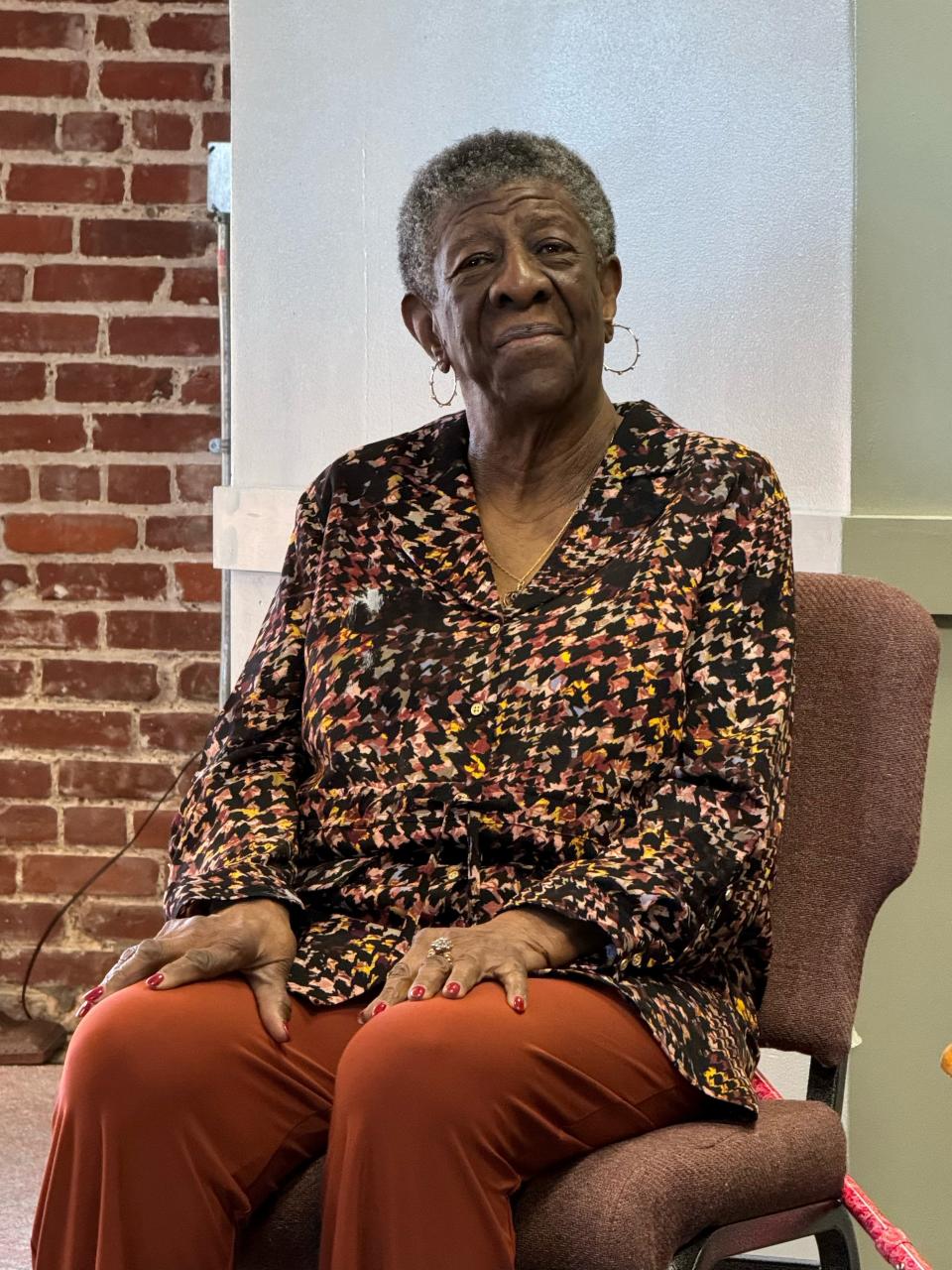

Jones turns 91 on March 28, and the Louisville Civil Rights icon says she’s passing the baton to the next generation of civil rights activists. In doing so she has some advice.

I listened as Jones' shared her story during a Listen, Learn, Act racial justice class at the Earth and Spirit Center earlier this month, which invites Black leaders, who are experts on racial issues that plague our city, to speak to the community. Jones is a precious intellectual resource. We must take the time to listen and intentionally carry her baton forward with a true understanding of Louisville's racial equity challenges.

The advice that changed Mattie Jones' life

Jones' advice doesn't look much different from the advice she received from her mother as a young college student. Her mother's guidance helped launch Jones into seven decades of activism.

The University of Louisville wouldn't hire Jones for a work-study program because she was Black. Jones could type 75 words per minute and she knew shorthand. She remembers the man who interviewed her recognizing her competence, even complimenting her penmanship, only to point to the white ladies who worked in the office and say, “They won’t work with you.”

“I was burning up with anger,” Jones said.

She was so upset she walked home that day instead of riding the streetcar back across town. At home, she said her mother sat her down for a reality check, telling her racism would be something she would deal so as long as she had a Black face.

Jones' said her mother told her, “you're not gonna win this battle by yourself. You've got to join in … say your prayers and ask for help.”

She would spend the rest of her life joining in.

Jones joined the Black Workers Coalition and handled employment complaints. She marched with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. She protested in Louisville against segregation in public schools and for open housing. Jones is a founding member of the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression and she also fought for the Justice Resource Center in Louisville alongside the late Rev. Louis Coleman.

Now, Jones is a treasured resource to Louisville’s next generation of Civil Rights leaders. Her home is called “the community house” for a reason. You don't need an appointment to stop by or to pick up the phone. She is there for you. ”My role should be leading these young people that are wanting to become leaders,” she said. “I will work with you and do everything possible, but march or protest... [My] legs and feet and age won’t let me.”

Community members seeking to enact change must not squander her generous offer. Drink in all of her advice. Louisville is not finished fighting, and Kentucky's legislators are not finished chipping away at the gains Jones' generation of social justice leaders fought long and hard to obtain.

Mattie Jones wants Louisville to be better prepared

Jones said she did not protest when Louisville Metro Police Department officers killed Breonna Taylor because the protests turned violent. Instead, she spoke to leaders, telling them that violence was not the way. She watched the protests of 2020 unfold and said she that Louisville was caught unprepared. “[Protestors] just got out there and acted," she said, "I don’t criticize them, it was all well and good.” But when so many people showed up from all over, she said it added chaos and fueled some of violence that took place.

Jones said she’s never thrown a rock or acted out during protests and she credits the coaching she received. “Dr. King did not let us hit the streets unless we had some training,” she said. She went to the Highlander Folk School in Grundy County, Tennessee, like many other leaders of the Civil Rights Movement. “We were trained how to act and react, not just when crisis hit us.”

When you organize, she said you always have to be looking for the ones who are going to come in and be disruptive, “That's why you need old timers like us to try to steer you.”

Jones is one of the Civil Rights Leaders who paved those first pathways of the movement. The ones who championed and obtained open housing so Black people could live where they wanted. The ones who fought for the simple ability to go shopping and try on clothing in department stores alongside white people. But Jones fears the movement relaxed too much in the wake of those wins. “We did not carry the message to this next generation," she said, "African American children today don't know the struggle that we went through.”

Though Jones saw disorganization during the 2020 protests, she also saw hope. She said she saw the community, white and Black, coming together and it gives her deep satisfaction within. “Here is a change that has been made,” she said.

First, you have to set yourself free

Like so many other things in life, Jones' said that social justice work has to start from inside you, the work truly begins with setting yourself free.

Jones explained that you feel free after something changes deep within you. For her, it was that day U of L denied her the work-study program.

From there, she says it takes strong, trusted leaders, who are accessible and available to those looking for guidance. Like Jones' mother was there to help guide her. Jones is adamant that you have to be able to talk to someone to help you deal with what is happening around you along with the emotions that bubble up as a result. She said you must be able to express yourself. Jones wants to be that person for Louisville's next generation of leaders and activists. ”We have to talk to people,” she says, “We have to show them the way.”

Everyone’s path to inner freedom looks different but Jones says one thing is for certain: If you don't free yourself, then you remain afraid to speak out. And if you don't speak out about what is right, then you continue to uphold what is wrong.

More about Listen, Learn, Act

The day I attended, Mattie Jones was the only person of color in the room. Mostly retired white people gathered with the intent of learning how to become better allies in our community. Di Kerrigan and Deborah LaPorte began Listen, Learn, Act racial justice classes at the Earth and Spirit Center with much of that same energy. They wanted to educate themselves and others as an intentional response to the police killing of Breonna Taylor. In anger and despair, they felt the need to show up and push for justice in response to this horrific incident. Rev. Joe Phelps has long been active in Louisville social justice and facilitated the conversation with Mattie Jones who said with affection that she was only there because Phelps had asked.

Bonnie Jean Feldkamp is the opinion editor for The Louisville Courier Journal. She can be reached via email at BFeldkamp@Gannett.com or on social media @WriterBonnie.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: She marched with MLK. What advice does this KY Civil Rights icon have?