Letters by British mountaineer who disappeared on Everest in 1924 published

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Letters from the British climber George Mallory, who disappeared on Mount Everest in 1924, to his wife Ruth have been published online by his former Cambridge University college.

The mountaineer and explorer was 37 years old when he and his climbing partner Andrew Irvine vanished close to the summit of the highest mountain in the world.

Mallory’s body was found 75 years later in 1999 – and there is still debate about whether the pair had made it to the top.

The first documented successful ascent of Everest was not until 29 years later, in 1953, by New Zealand climber Edmund Hillary and Tibetan mountaineer Tenzing Norgay.

Mallory, a member of Britain’s Alpine Club, studied at Magdalene College in Cambridge before becoming a schoolmaster. He served in France during the First World War before returning to England in 1919.

It was on his third expedition to the mountain that he vanished. When asked why he wanted to climb Everest, Mallory had reportedly said: “Because it is there.”

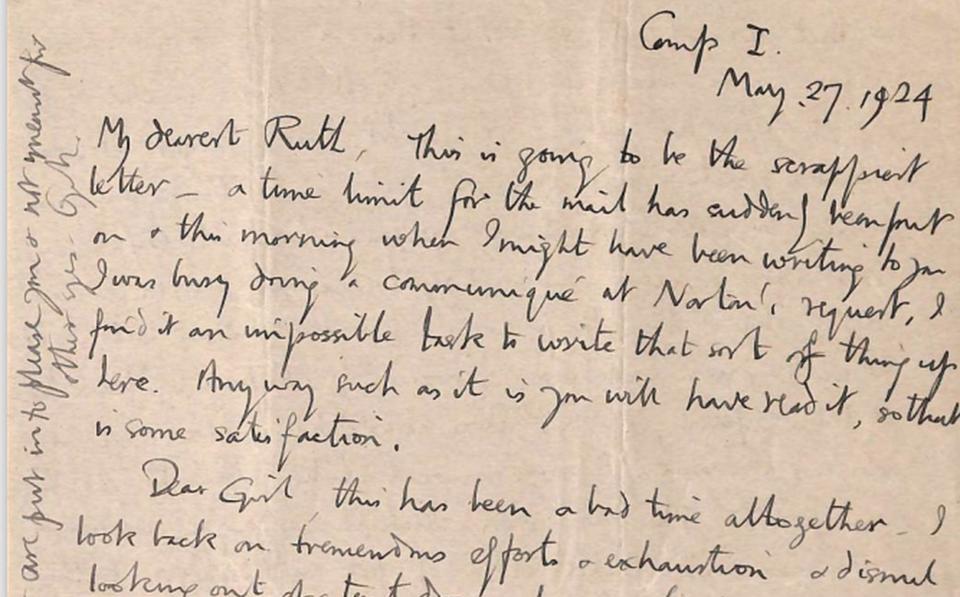

Now, Magdalene has published a collection of letters online in the centenary year of Mallory’s disappearance. The majority of the correspondence is between Mallory and his wife Ruth, from the time of their engagement in 1914 until his death on Everest ten years later.

It includes the last letter from Mallory to Ruth before his final Everest summit attempt, in which he said the odds were strongly against him.

He wrote: “Darling I wish you the best I can – that your anxiety will be at an end before you get this – with the best news. Which will also be the quickest.

“It is 50 to one against us but we’ll have a whack yet and do ourselves proud.” He signed off with: “Great love to you. Ever your loving, George.”

The only surviving letter from the Everest period in the archive from Ruth Mallory to her husband is also published online. She wrote: “[I am] keeping quite cheerful and happy but I do miss you a lot.”

“I think I want your companionship even more than I used to,” she added. “I know I have rather often been cross and not nice and I am very sorry but the bottom reason has nearly always been because I was unhappy at getting so little of you.

“I know it is pretty stupid to spoil the times I do have you for those when I don’t.”

The letters cover topics including Mallory’s first reconnaissance mission to Everest in 1921 and his second expedition there in 1922, when seven Sherpas were killed in an avalanche. Mallory blamed himself for their deaths.

His service in the First World War is also described in the letters, including eyewitness accounts of being in the Artillery during the Battle of the Somme.

Three letters that were retrieved from Mallory’s body in 1999, which had survived for 75 years in his jacket pocket, have also now been published online.

These are a letter from his brother, Trafford Leigh-Mallory, a letter believed to be from Stella Cobden-Sanderson, a supporter of his expedition, and a letter from his sister Mary Brooke, written from Colombo in Sri Lanka.

In the latter, Ms Brooke writes: “I hope you have been getting the weather reports all right – it will be very interesting to hear whether you can trace a connection with our weather and how long afterwards.

“Since sending you the observatory report yesterday we have had the most terrific storm... It was most violent for nearly three hours so if you get the same you had better be on the look out...”

Magdalene College archivist Katy Green said: “It has been a real pleasure to work with these letters.

“Whether it’s George’s wife Ruth writing about how she was posting him plum cakes and a grapefruit to the trenches (he said the grapefruit wasn’t ripe enough), or whether it’s his poignant last letter where he says the chances of scaling Everest are ‘50 to one against us’, they offer a fascinating insight into the life of this famous Magdalene alumnus.”

The letters are free to view on the Magdalene College website.