Law enforcement, mental health experts say Mount Horeb school shooting was difficult situation with few easy answers

If you or someone you know is dealing with suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or text "Hopeline" to the National Crisis Text Line at 741-741.

MOUNT HOREB – On May 1, 14-year-old Damian Haglund approached Mount Horeb Middle School with — what appeared to be — a firearm.

According to the state Department of Justice, the teen didn't follow officers' commands to drop the weapon. Instead, the DOJ said Haglund pointed the gun at officers, which prompted police to fatally shoot him.

The DOJ later identified the weapon as a Ruger .177 caliber pellet rifle, which is a type of air gun that shoots pellets instead of bullets, mostly used for target shooting or hunting small animals. The department declined to specify which version of the rifle Haglund had or provide a description or photo.

The details — an eighth-grade boy, his death, a pellet gun, a small tight-knit community — reveal a complex, tangled web that complicates any theory into why the tragic incident happened in the first place. The events have also left many with tricky questions over what exactly transpired, the boy's intentions and whether his death could have been prevented.

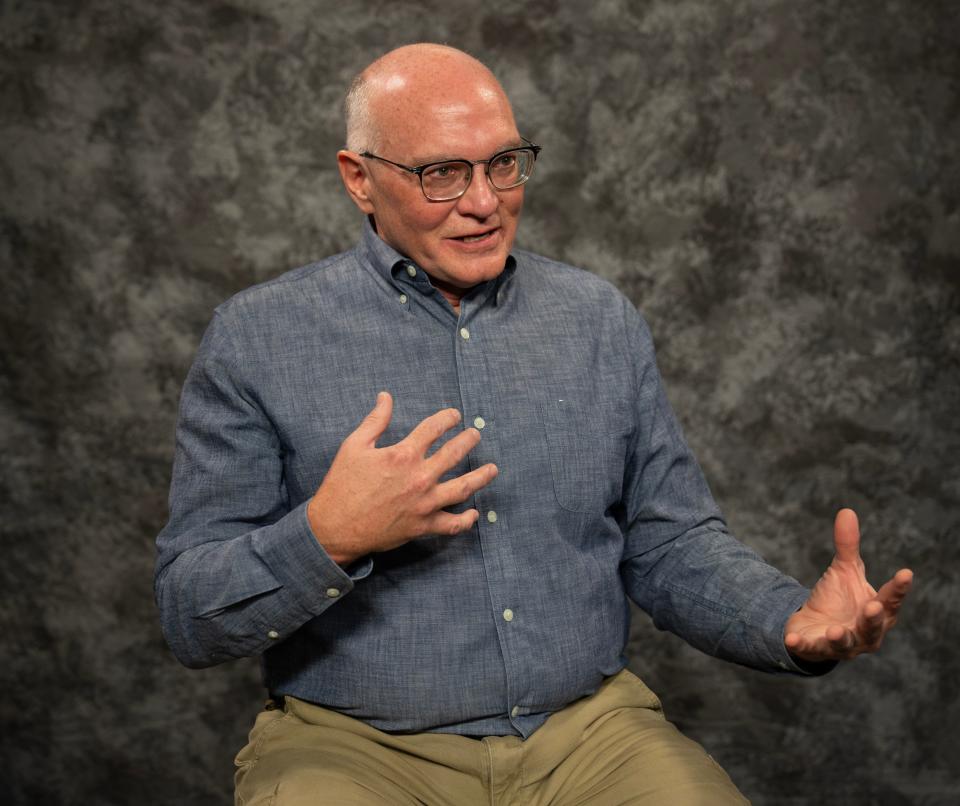

"We are in this time where we often see cops shooting people in unjustified ways, which is definitely a big social problem right now," said Travis Wright, an associate professor of counseling psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. "But this wasn't a cop doing a cold call warrant on an adult who was caught off guard. This was somebody in a defensive act protecting children."

Wright holds a unique perspective. He specializes in working with children who have experienced trauma, and is a father of two from Mount Horeb. He rushed to the school May 1 with the same fear and worry as the other parents and has also provided emotional support to staff, parents and students in the days following the chaotic scene.

Stepping back and framing these tricky questions, said Wright, can at least begin the process of arriving at the answers. But those questions, and their answers, will take time as his community continues to grieve and process the collective trauma.

"When you don't feel safe, our brains are hardwired to think in black and white. You stop thinking in grays, you stop trying to figure out the nuances in order to survive," Wright said.

While the investigation is ongoing, experts from both law enforcement and mental health backgrounds spoke to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel to shed light on the circumstances leading to Haglund's death.

Former law enforcement officers said pellet guns and firearms are nearly impossible to tell apart. A retired police sergeant and former SWAT crisis negotiator also explained what runs through officers' minds in active shooter scenarios.

Meanwhile, behavioral health experts said it's impossible at this point to ascertain Haglund's exact intentions, which ultimately ended his young life.

Split-second decisions are about survival and others, former officer says

Retired Dallas Police Department Sgt. Larry Gordon was a crisis negotiator for the department's SWAT team for more than 13 years. Through decades of working in law enforcement, he's responded to active shooter scenarios of all kinds.

Gordon said when a weapon is pointed at officers, they're trained to stop the shooter — and fast, because a bullet can travel up to three times the speed of sound.

"Basically, what I'm saying is: (if you) wait for the 'pow,' you're already hit," said Gordon.

He said officers are trained on something called "the OODA loop": observe, orient, decide and act. The decision-making model, which originated from and is still used in the military, is used to approach chaotic situations.

This means officers have to act based solely on information they already know, Gordon said.

In the Mount Horeb case, officers were informed of a teenager with a rifle on school grounds. When Haglund didn't put down the weapon, Gordon said, officers probably considered themselves in danger and acted in accordance with their training.

The Journal Sentinel asked the DOJ to address whether law enforcement officers have difficulties distinguishing between firearms and air guns, such as pellet guns or BB guns. The DOJ declined to comment, citing the ongoing investigation.

Still, the officers' response presents another cycle of questions, at least on a personal level, for Mary Kay Battaglia, executive director of NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) Wisconsin: Could police have disarmed Haglund without killing him, such as by shooting him in the arm or leg?

In her professional capacity at NAMI Wisconsin, Battaglia has attended many crisis intervention training programs organized by local law enforcement agencies. It can be startling, she said, to observe their response when it comes to restraining individuals, especially since her role is to help improve relationships between police officers and individuals with mental illness.

But she's reminded each time that the job of police isn't just to protect themselves; it's also to protect the wider community.

"I don't know how to answer this without throwing myself under the bus, because those are the two things I keep thinking about," Battaglia said.

That dual thinking — whether the teen's life could have been spared and the impossible position of the police — makes a lot of sense to Wright, who said that when life feels threatened, we think in very black and white terms.

"When you're in survival mode, the frontal part of your brain shuts down. You can't cognitively ask yourself these questions," Wright said.

Wright, who worked with students, parents and staff in the aftermath of the Uvalde shooting in Texas May 24, 2022, said the officers there were overly cautious. Indeed, the U.S. Department of Justice found that the responding Uvalde officers bucked accepted practices in an active shooter situation, which cost the lives of 19 children and two teachers.

In contrast, officers took swift action in Mount Horeb, Wright said.

In general, law enforcement experts do not recommend officers disarm people by shooting them in the limbs for several reasons, including the likelihood of hitting an artery and killing them.

Gordon, the former SWAT negotiator, said because of how little time officers have to react to an active shooter, it is "almost impossible" to hit a specific body part, such as a hand or leg. Instead, once the decision is made to shoot, Gordon said, officers are trained to hit "center mass," or the most exposed area of the shooter, because it's the easiest target.

Deciphering Haglund's intention is tricky, mental health experts say

The state DOJ said Haglund was fatally shot by police after he pointed his pellet gun toward them and refused to put it down. The agency declined the Journal Sentinel's request for body camera footage due to the ongoing investigation.

According to the DOJ, "lifesaving measures were deployed" before Haglund died at the scene. Besides Haglund, police said no one was hurt.

In some previous school shootings and mass casualty events, law enforcement officials have been able to take suspects into custody alive, such as the 2018 Parkland school shooting.

Gordon said if a shooter responds to officers' commands — for example, to lie on the ground, drop their weapon, or put their hands behind their head — police can arrest them without using lethal force. For example, the Parkland shooter killed 17 people, but when police attempted to arrest him, officers say he surrendered without incident.

But if an active shooter runs away or refuses to comply, Gordon said officers are trained to act.

De-escalation is an important component of crisis intervention training programs, especially when someone is having a mental health emergency. But that underscores another difficulty stacked against officers responding to a crisis: The presence of law enforcement can sometimes intensify somebody's actions, said Debi Traeder, chair of Prevent Suicide Marathon County.

In the Mount Horeb case, Gordon said reports that Haglund pointed his weapon at officers and did not follow orders to put it down could indicate a "suicide-by-cop" scenario. That is when someone attempts to die by forcing a law enforcement officer to use lethal force, according to the Police Executive Research Forum.

However, Gordon said that's a determination officers can only make after the fact, not in the moment.

It's also impossible to know Haglund's true intentions. Writings from the eighth grader's blog show an obsession with Columbine that, for Battaglia, suggests obsessive thinking, social isolation and loneliness — which doesn't, in and of itself, indicate he had mental illness or was suicidal, she said.

"It almost seems like it was a glorification of something he ruminated about, which is different than suicide-by-cop," Battaglia said.

Wright also isn't so sure. Just because someone makes a potentially lethal decision doesn't necessarily indicate intent, Wright said.

"That it was a pellet gun either says he didn't fully understand how the gun worked, or the potential impact of his actions. Or it says he knew exactly what he was doing and he didn't really want to hurt anybody, but he did want to get hurt," Wright said.

Pellet guns and 'real' firearms nearly impossible to tell apart, experts say

Officials haven't confirmed which version, but the DOJ said Haglund's weapon was a Ruger .177 caliber pellet rifle. While not a true firearm, Washington County firearms instructor Jeff Pharris said it is very difficult to see the difference between them at a glance.

"If a pellet gun is pointed at you, immediately, there's no way that you can tell simply from the front that it's a pellet gun," said Pharris.

Pharris said it is sometimes possible to distinguish between the two from the side, depending on the make and model. For example, some pellet guns' rear sights, used to aim, are closer to the front of the weapon than a traditional rifle's would be.

In contrast to firearms, air guns — like pellet guns or BB guns — typically use compressed air instead of explosives to launch metal or plastic projectiles.

Pharris said pellet guns, used for target shooting or hunting small animals, have become more powerful over time.

"When I was a kid, my brothers and I would chase each other around the backyard and shoot each other with pellet guns with just our Carhartt (jackets) to protect ourselves," he said. "But the guns have advanced tremendously since then."

Pharris pointed out one pellet rifle for sale on Ruger's website has a muzzle velocity, or bullet speed, of 1,200 feet per second.

"That's faster than the speed of sound," Pharris said. "That's like 800 miles an hour."

The pellet itself is very small, so it would not do the same damage as an AR-15, he said. But Pharris said it could still cause severe injuries.

"It's not just, 'Oh, that's going to sting a little bit,'" Pharris said. "No, it's definitely penetrating skin."

While some pellet guns are marked with an orange tip, this is not legally required. Federal law requires only airsoft guns, which shoot plastic pellets and are commonly used recreationally, to have an orange tip so they aren't confused with real guns.

But even then, Pharris said he's seen gun owners camouflage the orange markings with black electrical tape or spray paint because they want it to appear real.

"Unfortunately, there's also been instances that I have heard of where people will have a real firearm and put a half-inch ring of orange duct tape on the end of the barrel to fool people into thinking it's just a toy gun," he added.

That inability to distinguish pellet guns from firearms adds yet one more layer of questions as the community continues to reel. The unknowns — coupled with the grief, anger and fear — make processing the trauma that much harder, said Shanda Wells, behavioral health manager at UW Health.

"When someone close to us, a child, is killed, it's harder for us to make sense of it," Wells said. "The whole process of processing trauma and being able to tell ourselves a story about what happened … becomes a lot more complicated when the story isn't clean."

Quinn Clark is a Public Investigator reporter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Contact her at qclark@gannett.com. Natalie Eilbert covers mental health issues for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. She welcomes story tips and feedback at neilbert@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Experts grapple with difficult decisions in Mount Horeb school shooting