Kings of Leon’s Caleb Followill: ‘Nepo babies? I’m not giving my kids s***’

It’s mid-morning in Nashville, and across the screen, Caleb Followill is walking me around his office space, pointing out a golden awards’ statuette, and framed pictures, and the books he read recently: Crime and Punishment, The Art of War, The Old Man and the Sea; John Grisham, Dan Brown, Truman Capote. He explains how each item contributed in some way to the new Kings of Leon album. “And I could go song to song and point them out,” he says. “Everything in here is like a puzzle.”

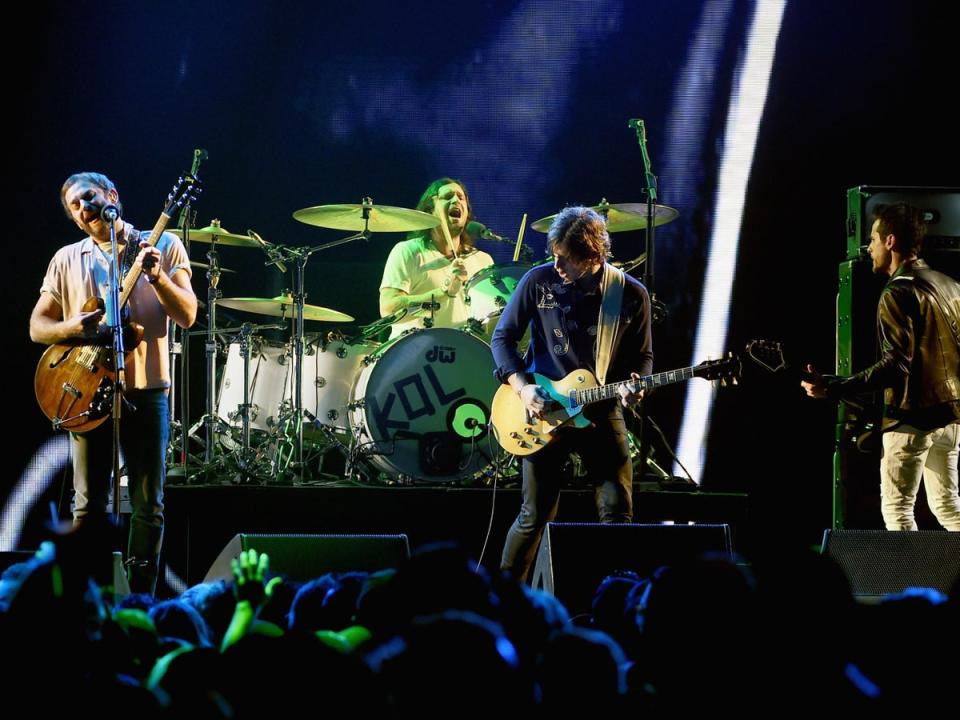

Can We Please Have Fun is the ninth album by the band that Followill, his brothers Nathan and Jared, and their cousin Matthew, formed in Nashville in 1999. It is also their most intimate for some time – weighted by the sentimentality of objects, by the loss of their mother, and by a newfound freedom they found in writing songs without a record label. “It was just kind of like our little secret project,” he says. “It was just about doing something we were proud of and that made us happy.”

It’s a record that also recaptures some of the scuff of the Kings of Leon’s earliest records – 2003’s Youth & Young Manhood and 2004’s Aha Shake Heartbreak, when the band were the foremost southern representatives of an American rock’n’roll revival that bloomed on British shores in the Noughties. That was before they released “Sex on Fire”, which roared to No 1 in the UK in 2008, spending 127 weeks on the chart (it’s now well on the way to one and a half billion streams on Spotify), and its follow-up “Use Somebody”, which also became a chart fixture for the next two years.

Followill credits the return to their roots to the album’s producer, Kid Harpoon. Famed for his work with major pop acts such as Harry Styles, Maggie Rogers and Miley Cyrus, the producer was contacted by the band because “in our minds, some of the songs we were writing had the potential to cross over”, Followill tells me. To the band’s surprise, Kid Harpoon spoke of their earliest albums as musical touchstones.

Followill was struck by it. “Hearing your early music is kind of like if you have an answering machine on your phone, and you hear your voice and think ‘ahhh that’s not what I sound like, is it?’” But under their new producer’s gaze the band came to consider their early approach afresh, to see that maybe in the intervening years they’d lost a little of their grit. “So he found a way to bring some of the dirty back to our music.”

Like many bands keen for success, Followill concedes that at times his band were so desperate to be liked that they fell to “songwriting by committee”. In an effort to win over particular audiences, he says, they would try new approaches – moments that might be inaudible to many, but that he could hear clearly. “And then you realise that’s not how this is meant to work,” he says. “You’re meant to write something that means something to you, something that comes from your heart, something that only you have. And then when you tap into that, you create something beautiful to yourself, and that’s usually the thing that people gravitate to.” Can We Please Have Fun marks a return to Followill writing solely for himself and his band. “On this record,” he says, “I can selfishly say I didn’t think about anyone.”

In those early days, while British audiences swooned, America remained resolutely unmoved. He pauses and corrects himself. “I feel like I’m pinning too much on America,” he says. “It wasn’t America that wasn’t getting it, it was Nashville that wasn’t getting it.”

He writes about this time on the recent single “Mustang”, recalling the days when he and Nathan had moved to Nashville in the late Nineties with the fierce belief that they could make it as songwriters. They wrote what were by his own admission “some sh***y little songs” and began touting them up and down Music Row, home to the major music publishing houses and record labels. “We would go knocking on doors, and some poor secretary would open the door and we would just start singing, and most of them would close the door in our face,” he remembers. “But eventually someone left the door open and we got a publishing deal.” Still, the kind of country music success they dreamed of evaded them. “Faith Hill wasn’t singing our songs,” he says. “Tim McGraw didn’t want any of them.

“So we ended up having to leave this town and go to New York, and everyone opened the door and everyone offered us a record deal,” he continues. “And we came back to Nashville like ‘We showed you!’” Nashville remained unruffled. Even today, he concedes, he craves his home city’s approval more than any other, and still it seems to elude him. “I’ll go to a restaurant and some country singer will walk in with his hat on and his tight pants and not a whole lot of talent, and he gets everybody turning their heads,” he says, and his voice is not bitter but curious. “Not that I’m necessarily looking for that, but nobody notices me when I walk in the room. Like, what do I have to do?” He will admit that it’s shifting. “We do hold the record for the largest concert in Nashville history,” he concedes. “And we are in the Nashville Hall of Fame. But it took us a while.”

We are in the Nashville Hall of Fame. But it took us a while

What kept them going was the stubborn belief drilled into them by their mother, Betty-Ann, who passed away in 2021. Followill speaks about her today with great tenderness. “I know every mother believes in their child, but she believed in us way more than you probably should believe in your kids,” he says. That belief made up for plenty of shortfalls in their upbringing as the children of an itinerant preacher father in the Deep South.

“We didn’t have any money,” he recalls. “A lot of people are far worse off than we were, but we went to bed hungry and we were embarrassed by the clothes that we wore as kids. But while all that was happening, our mom was still saying, ‘You guys know that you’re going to be really special. You guys are going to do something great.’ I don’t know if she fully believed it, but I know that she was going to make us believe it.”

When success did come for the band, their mother wore it proudly. “She had a licence plate: ‘Under the influence of Kings of Leon,’” Followill laughs. And when her sons occasionally fell out, as rock stars are wont to do, it was their mother who pulled them back into line. “As soon as we were fighting with one another, she would always come to us as brothers and be like ‘Alright, settle down,’” he says. “She would always bring it back to what it was – we weren’t fighting about our roles in the band, we were fighting about something from when we were eight years old that we didn’t get out of our system. She always reminded us of who we were and how crazy this opportunity is, and to not go mess it up like so many people do.”

The new album is not necessarily about Betty-Ann, Followill says, but in many ways it was inspired by her. “I just really wanted to make an album that she would be proud of. And I was thinking of her every step of the way. I feel like we all were. When something great would be happening we would all look at each other like ‘man, she would love this.’” The album is dedicated to her.

One of the most important lessons Followill feels his mother taught him is “You don’t have to have everything to go get everything. You can start with very little and go very far if you work hard.” I wonder whether his own children, with the American model Lily Aldridge, will understand this lesson or fall back on the privilege of their parents’ success. He smiles. “Nepo babies?” he says. “No, I’m not giving my kids sh**. They gotta get it themselves.”

Look for Betty-Ann’s diplomatic presence elsewhere on Can We Please Have Fun, and you might alight on the track “Nothing to Do”, a protest song of a sort that rails against internet culture and the fear-based news cycles that only serve to polarise societies. “‘Our wires got crossed and now we don’t speak,’” Followill quotes the lyric. “That’s something that happened with a lot of us, especially here in the States,” he says. “Politics pulls a lot of people apart. We live in a time when there’s not 10 sides, there’s two sides in this country. And I’ve always been someone who thinks, how can you let politics or religion tear your family apart? How can you put so much faith in a politician that you’re gonna turn your back on your brother? You need each other.”

Over the years, Followill has tried not to be drawn too deeply into debate, particularly as a resident of a fraught Southern state. But perhaps as a result of dropping some of the band’s polish, of getting “some of the dirty back”, or simply the knowledge that the US stands in the heat of an election year, today he speaks in forthright, if broad-brush terms. Perhaps nervous of alienating audiences, there is no direct mention of Trump or Biden or Tennessee governor Bill Lee, or any of the specific issues that might concern voters – abortion, immigration, foreign policy – but more a general sense that this is a nation that, as Betty-Ann might’ve perceived it, still needs to get something from long ago out of its system.

“These people that you’re putting your blind faith in, this is not about love,” he says. “This is about numbers. And control. And power.” He softens, and checks himself a little. “I normally try not to be too political,” he says sheepishly. “But the older I get, the more political I get. It happens.”

‘Can We Please Have Fun’ is out now. Tickets to their headline show at BST Festival in Hyde Park, London, are on sale now.