Judge not convinced government immunity protects South Haven in fatal drowning lawsuit

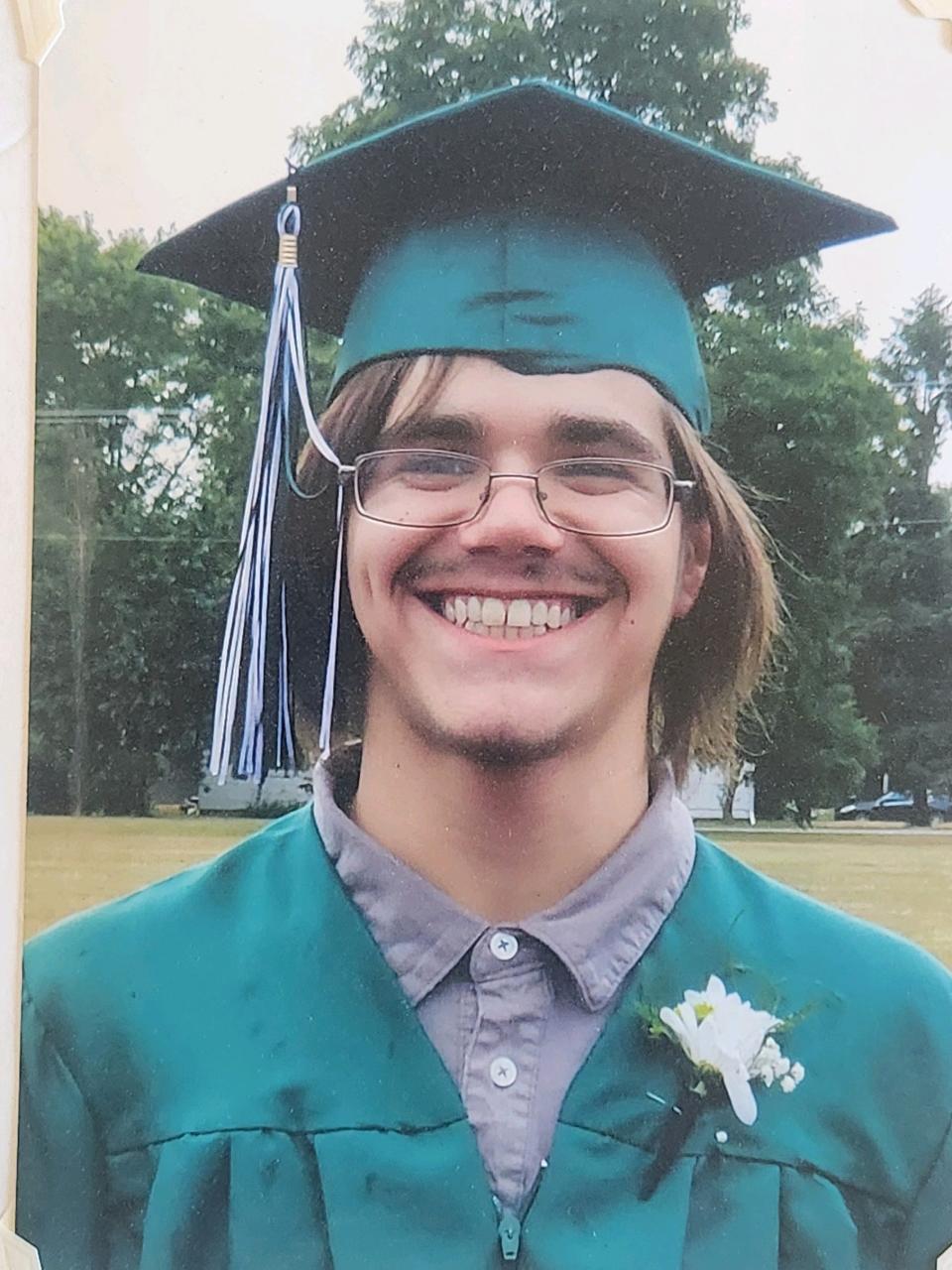

Brandon Chambers knew he was in trouble in the waters of Lake Michigan on that Sunday of Labor Day weekend. He had been pulled into a rip current and tried to save himself, clinging to a buoy for a few minutes before disappearing into the water and drowning. His body was recovered a week later.

Chambers was 18 when he died in 2020. Now, his mother is suing South Haven, claiming officials knew conditions were treacherous — two children had to be rescued from rip currents there two days earlier — but the red flags the city uses to prohibit swimming along its public beaches had not been posted where Chambers went into the water with two friends.

The city tried to get the lawsuit, filed last year in Van Buren County Circuit Court, dismissed on the grounds it is shielded by government immunity. But in a March 15 ruling, Judge Timothy Hicks denied that request, which allows the case to move forward.

A lawyer for South Haven, Thomas Beindit, declined comment, other than to say "we will vigorously pursue our claim."

Chambers' mother, Crystal LeDuke, said she was pleased with the latest victory but "it is going to be a long road ... we feel very fortunate to have made it this far in our Justice for Brandon mission, which is to get justice in the way of change, change that brings about prevention of what happened to Brandon and his loved ones."

The question of governmental immunity was an issue in the massacre at Oxford High School, when Ethan Crumbley, then 15, shot four students to death and injured seven other people. Last year, Oakland Circuit Court Judge Mary Ellen Brennan said Oxford school district employees and entities had government immunity and dismissed them from civil lawsuits.

Attorney Ven Johnson, who represented victims of the Oxford shooting and challenged governmental immunity for school officials, said the lawyer in the Chambers case "stands a chance" of prevailing, but "unfortunately for him, Michigan case law, up until now, has not been favorable and has gotten worse over time."

In the case brought by Crystal LeDuke in the drowning death of Chambers, a resident of Napoleon north of Jackson, the issue of governmental immunity comes down to a question about money: Did the city of South Haven make a profit from its public beaches? And did it use the cash it collects from beach parking fees, vendors, and other sources, for something other than beach maintenance?

LeDuke's lawyer, Ronald Marienfeld II, of Jackson, argues that the primary purpose of those two beaches is to generate a profit for the West Michigan city and that South Haven uses the cash for nonbeach costs such as vaguely defined fees for administration and the motor pool.

"It's a creative way to get money back into the general fund," Marienfeld said in an interview.

And that suggests the city is not protected from the LeDuke lawsuit, he said.

According to Judge Hicks' ruling, a government entity can be subject to claims that arise from its for-profit commercial activity, also known as a "proprietary function." It is an exceedingly narrow exemption to governmental immunity, and will now be the subject of a hearing in the Chambers case. A hearing date has not been set.

In his ruling, Hicks noted that what matters is where a government entity deposits its profits and how it uses the money.

"If profit is deposited in the general fund or used on unrelated events, the use indicates a pecuniary motive, but use to defray expenses of the activity indicates a nonpecuniary purpose," the judge said in the March 15 ruling.

Immunity an issue in Crumbly case: Oxford High officials were assured they wouldn't be prosecuted in mass shooting

Hicks cited an affidavit from an expert hired by Marienfeld, who said he believed the primary purpose of beach activities in South Haven was to produce a profit for the city. Marienfeld's expert also said in a deposition that money taken from beach funds was not spent on the actual expenses of managing the beaches.

In his lawsuit, Marienfeld said Chambers got into the water along a stretch of beach that was open to the public and where swimming was allowed. Red flag warnings that prohibit swimming, however, had been posted on nearby sections of the same beach, and had been posted along all South Haven beaches the day before.

The city, he said in the lawsuit, knew, or should have known, that the entire area was unfit for swimming. The lawsuit seeks a minimum of $25,000 in damages, including funeral and burial expenses, compensation for pain and suffering that Chambers endured, including the time when he was clinging to that buoy, and the loss to his family.

Two days before Chambers' death, the National Weather Service had warned that high waves would start building and could top 8 feet by Labor Day, the lawsuit said. It also predicted "some of the most dangerous conditions" of the season for the holiday weekend in South Haven.

Dave Benjanmin, co-founder of the Great Lakes Surf Rescue Project and an advocate for lifeguards on public beaches on the Great Lakes, said South Haven had just two drownings in the more than 40 years it had lifeguards, and one of those deaths happened after lifeguard hours.

Advocates: Lifeguards needed to prevent drownings on South Haven's beaches

Since doing away with lifeguards in 2001, 12 people have drowned, including Chambers in 2020 and Emily MacDonald and her boyfriend, Kory Ernster, in 2022.

The families of MacDonald and Ernster, who live in metro Detroit, are suing the city of South Haven in federal court in Grand Rapids. MacDonald was 19 and just finished her first year at Michigan State, and Ernster was 22, a recent MSU graduate. They were pulled from the water by a bystander but never regained consciousness. The city has asked the court to dismiss the suit, in part on the grounds of governmental immunity. Marienfeld said the request is pending.

According to Benjamin, public beaches are "truly moneymakers" for their communities, and that money can be used to hire lifeguards. Instead, many public beaches in Michigan, rely on a flag system. But those flags can't help spot, or help, someone in distress, and are no replacement for lifeguards, Benjamin said.

According to the Surf Rescue Project, there have been more than 1,200 fatal drownings in the Great Lakes since 2010, almost half of them in Lake Michigan.

In South Haven, the city's South and North beaches each have a pier and sand bars, which makes them especially prone to structural, longshore, and rip currents. Wind, waves, and incoming storms add to the list of dangers for swimmers in South Haven. The beaches are separated by the Black River.

Marienfeld, the lawyer for the families now suing over three drowning deaths in South Haven, calls it "this animal in the water."

Chambers' grandmother, Sue Chambers, told the Free Press in an email that South Haven advertises its beaches nationally.

"They invite families to come and play in the sun, sand, and water all the while knowing that it's not safe," Chambers said in a statement. "They have a responsibility to ensure, within reason, the safety of their tourists and visitors. Experts have shown that the flag system is fatally flawed, management of the flags cannot be done in a timely manner, and emergency services are too far away to save a drowning person."

The only logical answer to stop these "senseless deaths," she said, is lifeguards.

Contact Jennifer Dixon: jbdixon@freepress.com

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: South Haven claims government immunity in drowning; court disagrees