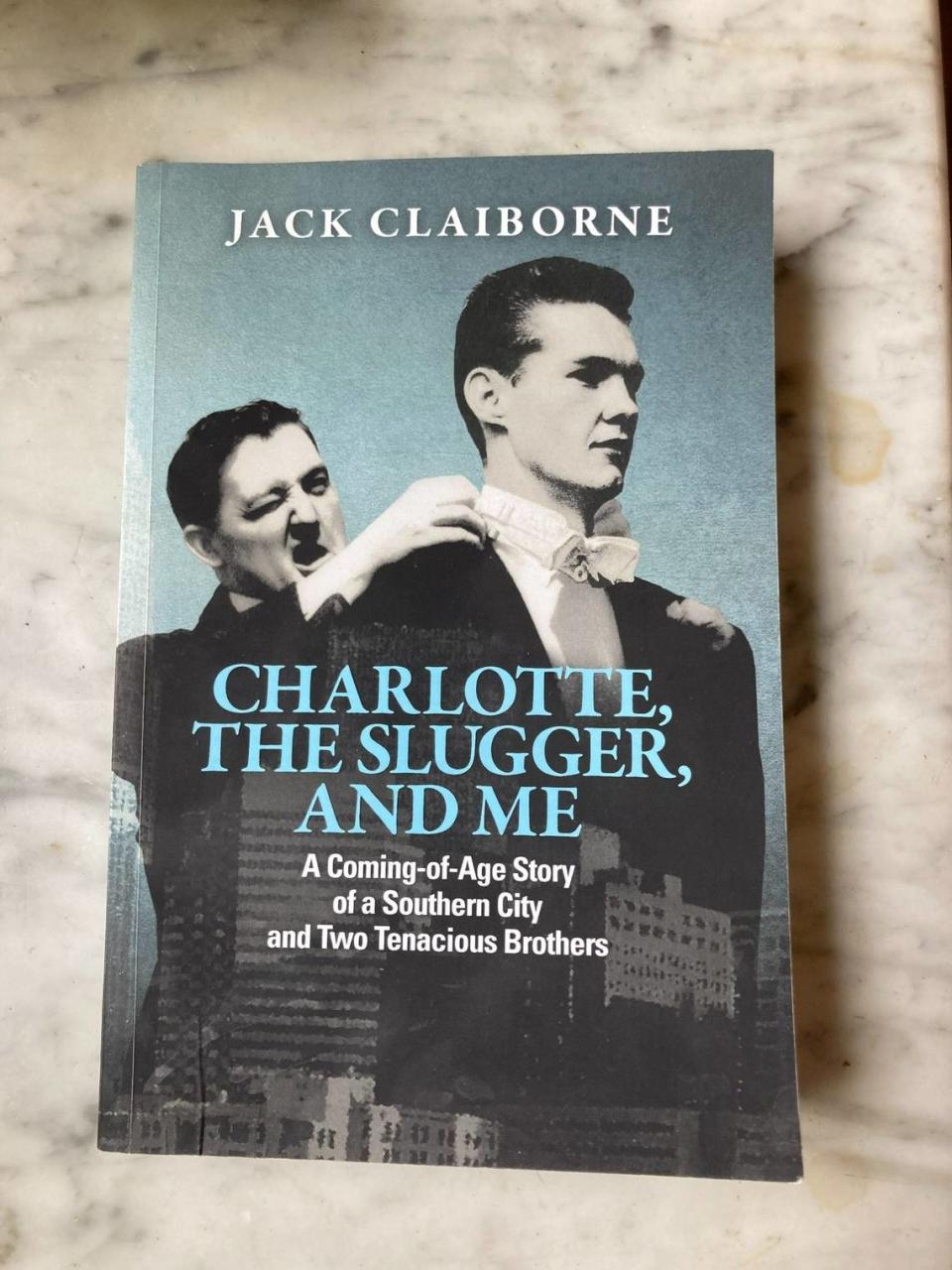

Jack Claiborne’s Charlotte: A tale of two brothers and the city that helped raise them

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In scenes so vivid they roll like film, former Charlotte Observer columnist Jack Claiborne, 92, gives us a memoir of growing up, alongside his scrappy younger brother Jimmy (“Slug”), in the “pushy little Southern town” of Charlotte. In “Charlotte, the Slugger and Me,” he writes of early hardship — the loss of the family farm during the Depression and the death of a devoted father when Jack and Slug are 5 and 4.

He tells of relatives who suggest the tykes be sent to Thompson Orphanage. Even with four older children and a rented farm in Newell to run, their mother, Minnie, won’t hear of it.

And he tells of the rainy day in September 1936, when Minnie corrals the six children into Charlotte to hear President Franklin Roosevelt at the new Memorial Stadium. Such a lucky day. The Claibornes happen on an affordable rental house on East Fifth Street, and soon they move to town.

Goodbye hog-killing and cotton picking. Hello, good schools, caring neighbors and a town bursting with intrigue and promise.

In a tale of both heartbreak and triumph, Claiborne takes the brothers, forever besting one another, on to UNC Chapel Hill and beyond — Jack as a prize-winning journalist and associate editor, and the late Slug Claiborne as a household-name restaurateur.

Q. You and Slug were merely tots — but scrappy tots — when heart disease killed your dad. Your mother was busy sewing, cooking and taking in boarders. Did the town of Charlotte in some ways serve as a father substitute?

A. Oh yes. On the farm we were isolated. The city provided many more opportunities — playmates and neighbors who took an interest in us. One neighbor gave us and his children Sunday afternoon rides in his Hudson Terraplane, introducing us to the city and its surroundings. We enjoyed warm relations with John Patterson, the corner grocer. As we got older there were the athletes and coaches at Central High who became our role models.

And then there were the Anderson brothers at the Mercury Sandwich Shop whose own up-from-the-bootstraps rise inspired us. And, of course, there were those wonderful women Sunday school teachers at Caldwell Church. They left a lasting mark.

Q. You describe Slug as “short and stout” and “ebullient and outgoing.” You, “tall and skinny” and “wary and withdrawn.” You spent your childhood jostling for position. He, the jock. You, the brain. Did that competition strengthen each of your innate skills?

A. Yes. I wanted to be as athletic as Slug, and he wanted to be as articulate as I. Mother usually entrusted me to run crucial errands, such as taking the rent money to the real estate office. But Slug, as her youngest child and the one who most resembled her, remained her favorite.

He was also the favorite of neighborhood playmates. When they were picking sides for a street game, they always chose Slug first. That made me work harder to show that I was faster afoot and a better catcher of passes or fly balls. The ebullient Slug, on the other hand, was the one who got us into events I wouldn’t have attended and introduced us to people I wouldn’t have met.

It was late in our lives when Slug surprised me by confessing that in our school days, he had been daunted by my achievements. Slug revealed that I had made it difficult for him because of all I had done the year before.

Q. You were in high school when your mother died of a cerebral hemorrhage. Unlike your siblings, you did not weep. You wondered then if it was because she “rarely showed you the warm affection she lavished on Slug.” Was such soul-bearing honesty hard for you to put into print?

A. Certainly. It is always hard to make yourself vulnerable. I am still puzzled by not being able to cry over Mother’s death and ashamed to admit I could have been so unfeeling. The truth is, I was probably stunned. All the security of my world had suddenly become unglued.

I am sure I loved Mother as much as any other family member but, just like my brother Harold had at ages 16 and 17, I quarreled often with her. She insisted I have an after-school job to help with the upkeep of the family while I wanted to be out at ballgames and dances with my high school friends.

I seem to have reminded her of her husband Henry Claiborne who she said pursued pipe dreams. She thought my wish to write for newspapers was beyond my reach, and I should stay with the restaurant business at Anderson’s. Nothing in her experience had prepared her for the opportunities that existed after World War II.

Q. There are several heroes in this book. A stand-out for me is your oldest brother Harold, who insisted after your mother’s death that you and Slug move in with him and his wife and give up your after-school jobs — yours at Anderson’s Restaurant — to devote yourself to your studies. Such generosity!

A. Harold had been a hero to our family many times. The last year we lived on the farm, 12-year-old Harold did the spring plowing, though he had to leap every few steps to keep the plow point in the ground. In the city he got a number of jobs to earn money, and he later dropped out of school in the tenth grade to work as a pressman’s helper.

During World War II he was a ball turret gunner on a B-17 and had part of his salary and flight pay sent home to support the family. After the war, when Mother faced a housing crisis, he bought a small house on the GI bill to get her out of the boarding house business and lighten her load.

When Slug went on his honeymoon Harold lent him his shiny new Chevrolet. Later, Harold drove me to Chapel Hill to begin college and provided me with his thick army blanket.

Q. You describe Charlotte of the 1930s and 1940s as a “welcoming place where you didn’t need a fortune or a pedigree to make friends or find favor.” Does today’s Charlotte retain some of those features?

A. Oh, yes. Charlotte is still an open and inviting city. Its leaders are still people who came here from elsewhere. There is no ruling class of “Old Charlotte” sachems managing things behind the scenes. District representation ensures that all parts of the city are heard from on vital issues.

Q. From your high school days of covering sports for the Observer, you dreamed of one day becoming the paper’s editor. But the higher-ups regarded you as a talented writer, unusually equipped to enlighten readers with your knowledge of the city, past and present. The resulting column, This Time and Place, was a hit. Do the regrets live on?

A. No. Though I was terribly disappointed at the time, as the years passed I have discovered they had done me a great favor. I do not like clashes and confrontation and have tried to avoid them, but as editor or managing editor I would have been hip deep in conflict and complaint from readers and publishers.

Over the years I have avoided most of that office turmoil and have advised others thwarted in their desire for managerial positions that they too may have dodged a bullet.

Management was correct in identifying my value to the Observer as a writer and when they wanted a 100-year history of the Observer they chose me to write it. I loved my job writing editorials and my “This Time and Place” columns.

Editor’s note: Jack Claiborne will talk about his new book at 7 p.m. Thursday , March 28, at Park Road Books, Park Road Shopping Center. Free and open to the public.

More arts coverage

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up here for our free “Inside Charlotte Arts” newsletter: charlotteobserver.com/newsletters. And you can join our Facebook group, “Inside Charlotte Arts,” by going here: facebook.com/groups/insidecharlottearts.