Two imprisoned Georgia men say they were wrongly convicted, and blame a single informant

An informant who has spent most of the last three decades in and out of lockups has helped send two men to prison for life in separate cases in Georgia — and is now a target of lawyers who say he made false claims in an attempt to spare himself time behind bars.

Sterling Flint, 54, was a key witness against Sonny Bharadia, who was found guilty of a 2001 sexual assault near Savannah. Flint testified against Bharadia as part of a deal with prosecutors in which he pleaded guilty to a lesser charge related to the crime. Flint’s DNA has since been found on a glove used by the attacker.

In 2009, six years after Bharadia’s conviction, Flint was taken into custody outside Atlanta and questioned about a load of suspected stolen goods in a car he was driving. Unsolicited, Flint provided an incriminating statement against Erik Heard, who had just been arrested in the fatal shooting of a young mother. Flint offered to obtain more information if he was released on bond. Flint later disavowed that statement at Heard’s trial, but a jury found Heard guilty.

Lawyers at the Georgia Innocence Project are trying to get Bharadia and Heard freed, saying both cases were deeply flawed. In courtrooms a hundred miles apart, they have made Flint part of their arguments. A judge recently granted Bharadia a new trial; a decision on Heard’s request for a new trial remains pending.

“Sterling Flint has reckless disregard for the truth and he has reckless disregard for the consequences for what he says, which makes him extremely unreliable,” said Olivia Vigiletti, a lawyer who volunteers with the Georgia Innocence Project.

She added: “The harm that Sterling Flint has done to these two men is exactly why law enforcement should be wary of relying on a witness who has every incentive to fabricate testimony in order to help their own case.”

NBC News could not reach Flint and tried to contact him through relatives, including an aunt who said she would forward the request but did not respond to follow-up messages.

In his 2009 interview with officers, Flint defended himself, saying he was “no bad person,” according to a transcript of the interview.

The use of informants in criminal cases, particularly those with an incentive to provide incriminating information about a suspect, is a contentious issue in the United States, with defense attorneys and civil rights advocates arguing that informants can be unreliable and cause innocent people to end up in prison.

Researchers have found that juries tend to believe informants — and are often unable to tell when they are mistaken or lying. A 2011 study of 250 wrongful convictions found that 52, or 21%, involved informants. Some states, including Connecticut, Florida, Illinois and Texas, have taken measures to regulate the use of informants.

If authorities use an informant, they need to make sure they can corroborate what the person is telling them, especially in cases where the informant is seeking to get something in return, said Summer Stephan, the district attorney for San Diego County and the incoming president of the National District Attorneys Association.

“You still have to solve crime and hold people accountable, but not at the risk of compromising justice or having someone wrongfully convicted,” Stephan said.

Flint’s statements weren’t the only pieces of evidence used to convict Bharadia and Heard; both cases also involved witnesses pointing out their faces — and the faces of alleged accomplices — on photo arrays. Both men’s lawyers have said the photo arrays were suggestive and flawed. For years, researchers have demonstrated the fallibility of eyewitness identification, particularly among traumatized victims.

There are also questions about crime-scene evidence. In Bharadia’s case, it took years to get the DNA testing that pointed to Flint. In Heard’s case, it took years for his lawyers to find that fingerprints lifted from the victim’s front door did not match his.

In both cases, the men’s lawyers say their prior lawyers failed to adequately raise issues around that evidence.

Georgia’s Office of the Attorney General has defended the convictions and argued against either man receiving a new trial. The office declined to comment.

The district attorney’s office in Chatham County, which prosecuted Bharadia, did not respond to requests for comment. The prosecutor who tried Bharadia’s case did not respond to requests for comment.

Tasha Mosley, the district attorney in Clayton County, where Heard was prosecuted in 2012, said she could not comment because no one who worked on the case remained employed there. The lead prosecutor on the case, now in private practice, did not return a request for comment.

Flint has spent a significant portion of his life behind bars, including seven prison stints since the 1990s, mostly for burglaries and theft, according to Georgia Department of Corrections records. In 2009, as he was telling officers that he had information about Heard, he also said he’d been diagnosed with skin cancer, did odd jobs, lived “one step from homeless,” was mourning the death of a brother, and was worried about the effect of his arrest on his family, including a daughter, according to a transcript provided by the Georgia Innocence Project.

Eight years later, when Flint was facing a drug charge in Fulton County, his lawyer told a judge that he’d known Flint for years and described him as a family man, a writer and the owner of a small security company.

“He’s imperfect, as we all are,” the lawyer, Carey Johnson, said, according to a transcript of the hearing. “But that being said, I can say he is, I consider him, a good guy.”

Around noon on Nov. 18, 2001, a woman returned from church to her apartment in Thunderbolt, Georgia, and found a man burglarizing it, according to court records. The man, wearing batting gloves, pushed her into a bedroom, took off her clothes, tied her to a bed, threatened to kill her, sexually assaulted her and fled. When she freed herself, she noticed several things had been taken from her apartment. She spoke to the police the next day.

Later that week, Bharadia called police to report that Flint, an acquaintance, had stolen his car, records say. As police investigated, they visited a friend of Flint’s in Savannah. The friend showed police items she said Flint had left in her house, including things reported stolen during the sex assault — as well as a pair of batting gloves that matched the victim’s description of what the attacker had worn, court records say.

A detective in Thunderbolt found out about this discovery and put Flint’s picture in a photo array for the assault victim, according to court records. She picked out photos of Flint and another man as possibly being the assailant. Flint was arrested, and he told police he had received the stolen items from Bharadia.

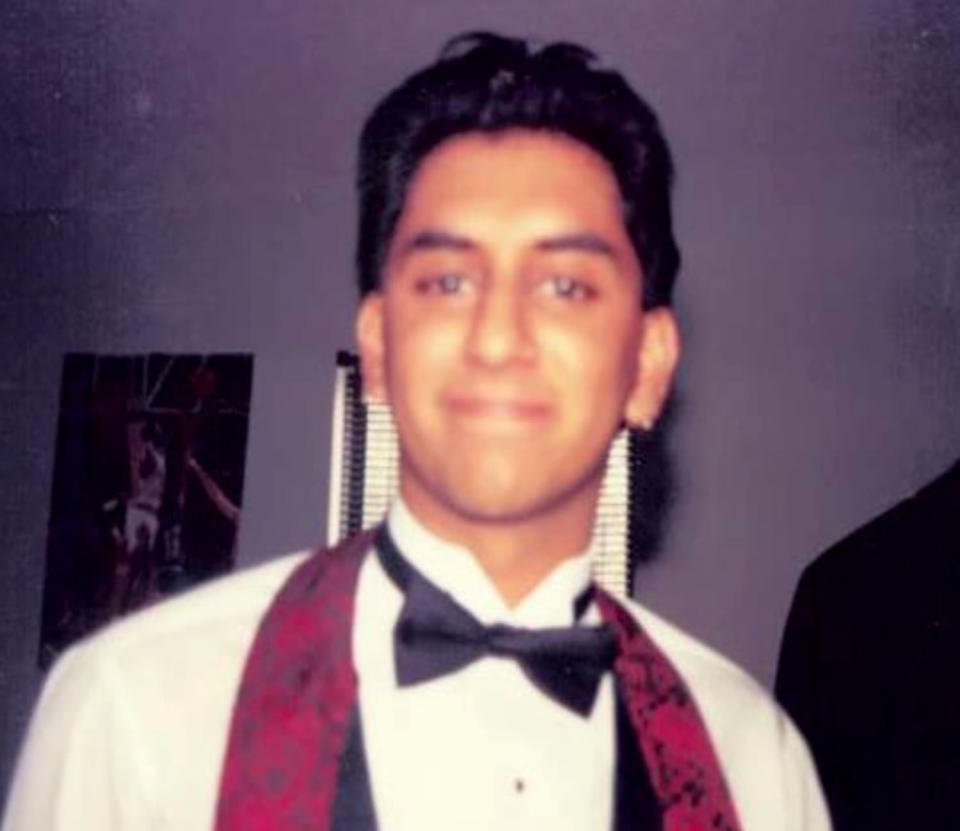

At the time, Bharadia was a sheetmetal worker living with his parents and was on parole for operating a stolen-car chop-shop, his lawyers said.

The detective put Bharadia’s picture in a photo array that did not include Flint, records show. This time, the victim identified Bharadia as her attacker. That photo array disappeared from the case file prior to Bharadia’s trial and was never recovered, court records say. But the detective used the identification to obtain a warrant for Bharadia’s arrest for the assault.

Flint was charged with burglary and theft by receiving stolen property. He pleaded guilty to the second charge in exchange for the first charge being dismissed. And he agreed to testify against Bharadia.

At Bharadia’s trial, Flint testified that Bharadia gave him the items found in his friend’s house. The victim identified the blue and white batting gloves as the ones worn by her attacker, and she told the jury she was sure that Bharadia was the person who assaulted her.

The jury convicted Bharadia of burglary, aggravated sodomy and aggravated sexual battery. He was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

Years later, Bharadia got a court order for DNA testing on the batting gloves. In 2012, the results came back: a single male DNA profile taken from the gloves matched Flint’s.

For another decade, both sides argued over whether the DNA result was grounds for Bharadia's conviction to be tossed. His fortunes turned last week, when a Gwinnett County Superior Court judge ruled that Bharadia did deserve a new trial.

The judge, Laura Tate, said she agreed with Bharadia’s argument that his past lawyers had failed to properly handle issues related to DNA testing, failed to raise questions about the missing photo arrays and the reliability of the eyewitness identification — and failed to challenge the truth of Flint’s statements.

It’s unclear how soon a new trial can take place. The state has 30 days to appeal the order.

In August 2009, after Flint had served time for the receiving stolen property charge, he was picked up in Cobb County in a car filled with goods suspected of being stolen. As detectives questioned him, Flint steered the conversation to another topic: an arrest in a murder case that had recently been on TV. A young mother, Sherveecka Pitts, 22, had been shot in a home invasion; her 17-year-old sister had witnessed it, and picked Erik Heard out of a photo array.

Flint told the detectives he had overheard the suspect on the street alluding to committing the killing, according to a transcript of the interview provided by the Georgia Innocence Project. Flint identified the man as Charles Black, which was an alias of Heard’s, authorities said at the trial.

The Cobb County detectives brought in two detectives from Clayton County who were investigating the murder.

Flint offered to find out more if he was able to post bond and be released, according to the transcript.

“If I can get outta here and this is — I swear to you guys, I could take you, you know, and you could hear things,” Flint said. “Whatever I need to do. Wire up. I’ll wire up for you and get all the information you need.”

Neither Flint nor the detectives agreed to any arrangement in the conversations covered in the transcription. But toward the end, Flint asked, “Do I get a bond?” and a Cobb detective responded, “Yeah, you get a bond.”

Flint’s statements remained crucial to the case against Heard — who had two young children and sold marijuana, according to his lawyers — when he went to trial three years later. Prosecutors submitted a video of Flint’s 2009 meeting with detectives into evidence. But when Flint was called to testify about it, he claimed that he did not remember any of it.

“I actually know nothing about this, nothing at all,” Flint said from the witness stand. “I’m ambivalent, I don’t know him, I don’t actually care what happens to him, but I’m not going to sit here and lie. I mean, I really don’t, I don’t care what happens to him. I don’t know him.”

Prosecutors appeared caught off guard by Flint’s reversal.

“So even here in this last two minutes you’ve changed your story?” Assistant District Attorney Jason Green said.

“That’s correct,” Flint replied.

The jury saw portions of the video several times. The victim’s sister also testified that she was “100% confident” Heard was the killer. The jury convicted him, and Heard was sentenced to life in prison.

In a petition for a new trial, the Georgia Innocence Project claims that investigators and prosecutors made several mistakes — including a reliance on a flawed sketch drawn from the recollection of the victim’s sister and the use of a “suggestive” photo array in which Heard’s face stood out among the others. Heard’s lawyers also accused prosecutors of withholding evidence that his fingerprints did not match those recovered from the victim’s front door.

Finally, Heard’s lawyers focused on Flint’s apparent bid to exchange information for freedom and his recantation on the witness stand. They described Flint in a court filing as “a jailhouse informant who provided unsubstantiated information to police in exchange for a promise that he would be released from jail on serious felony charges, and who later fully recanted his false statements implicating Heard.”

In court filings, the state Attorney General’s Office pushed back on the Georgia Innocence Project’s arguments, saying that Heard should not be given a new trial. The office denied withholding evidence and also said some of the Georgia Innocence Project’s arguments should have been raised sooner or had previously been raised and dismissed.

NBC News was not able to reach members of Sherveecka Pitts’ family, including the sister who witnessed her murder.

Back in 2009, as Flint, facing prison, told detectives he had information about the killing, he said he didn’t mean any harm. Whenever he had enough money, he said, he bought kids ice cream.

“I’m not a good dude, but I’m not a bad dude, you know?” Flint said. “I got a conscience.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com