Escaped from Rocky Point zoo, these monkeys ran wild in Warwick for years

WARWICK – When it comes to monkeys escaping from zoos, few breakouts can match the amazing story of what happened at Rocky Point amusement park in 1937.

With monkeys on the loose in Warwick for more than a few days, the escape couldn't help but generate headlines and go down in the history books while tugging at a few heartstrings and striking fear in some along the way.

Here's how the monkeys got out, who helped them afterward and what became of the Rocky Point monkeys, primarily drawn from accounts in the archives of The Providence Journal and its sister paper, The Evening Bulletin:

The great escape

Monkeys were an attraction at Rocky Point at least as early as 1876, when the Providence Morning Star newspaper ran a poem about their antics, beginning: "At Rocky Point the other day, We saw the monkeys in high play."

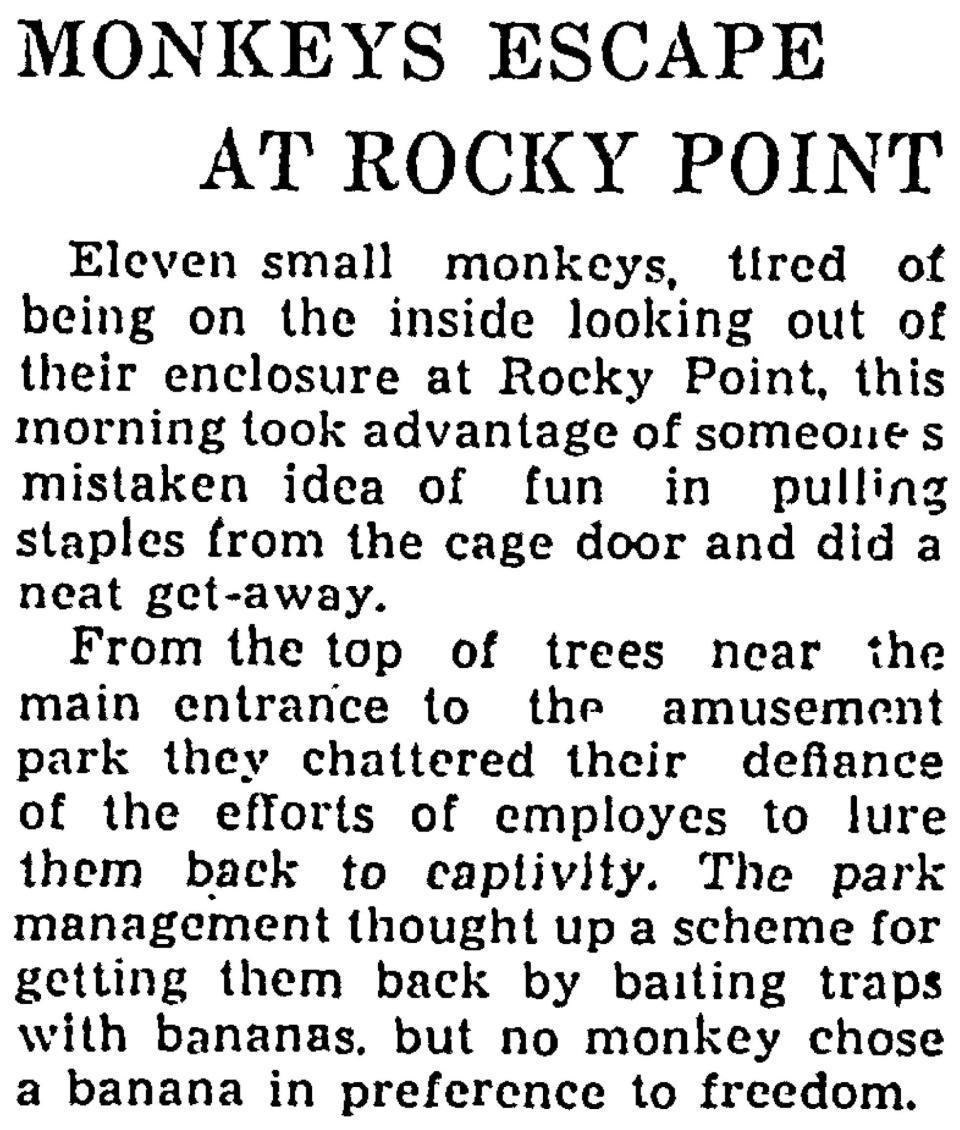

On July 19, 1937, apparently as a prank, someone tampered with the monkey cage on the midway and 11 broke free, finding refuge in trees near the entrance to the amusement park, where they chattered mockingly at park employees trying to capture them. Traps baited with bananas were of no use.

Read more: Why more than a few monkeys are named Jocko

The monkeys split into two groups. One group of five stuck close to the park, playing on the bleachers of the empty swimming pool. The other six took up residence in the woods behind the home of William and Harriette Geddes at 43 Rocky Point Ave.

Whenever the monkeys came up to the windows of the Geddes home, the couple's younger children, Dorothy, 7, and Bobby, 6, would make faces at their simian neighbors. "The monkeys try to do it, too," Bobby gleefully told a reporter.

In early December, a crew led by Martin F. Noonan, who oversaw Roger Williams Park in Providence – where the zoo had its own monkeys – captured two of the Rocky Point monkeys when they ventured into a nearby cellar. They were taken to the Roger Williams Park Zoo. But Noonan's staff grew tired and frustrated from repeatedly trying to catch the rest, so they gave up, leaving the monkeys to nature.

Can tropical monkeys survive a cold New England winter?

As the year wore on, Rocky Point neighbors fretted about what would become of "their" monkeys as winter loomed.

“Those poor little fellows will freeze to death," Noonan told one concerned resident, conceding there was nothing he could do other than to suggest that neighbors prop open a cellar window and rig it with a string to function as the door to a trap. He said residents should leave a banana or other piece of fruit in their cellar to lure the monkeys in. Zoo personnel would then come and remove the trapped monkeys.

No monkeys were caught this way, but the primates figured out a different strategy to deal with winter: They retreated to thick evergreen trees and sought shelter in some old boxes behind the Geddes house.

The monkeys' bodies adapted to their new climate, growing heavy coats of fur.

“Nature provides,” Noonan later observed.

Hurricane of 1938 brings disaster to monkey colony

The Geddes family emerged from their home after the Great Hurricane of Sept. 21, 1938, to find a landscape of devastation.

Fallen trees were everywhere, and the monkeys were nowhere to be seen.

Dorothy and Bobby searched what was left of their yard, but with no luck. The next day, the family went down to the water's edge at Rocky Point to search. They clung to a crazy hope that the monkeys had sought refuge in caves along the shoreline and somehow survived.

But that hope was dashed. The Geddes had searched for hours, but found nothing.

When dinnertime rolled around, the dejected family headed back home. There, on a toppled tree in the backyard, all six monkeys were perched!

But, within days, the Geddes' joy would be tempered: the oldest male monkey, whom Dorothy and Bobby had named Grandpa, had been badly shaken by the hurricane, seemed sullen, and then died.

`Grandpa' not the only loss

Soon after Grandpa died, three baby monkeys were born, including Tommy and Annie, children of one of the original escapees who had been named Susie.

But the following summer, tragedy struck again: An entertainer at a Warwick dine-and-dance club thought his act would be improved by the addition of a monkey. He trapped Susie. He put a chain around her neck and a belt around her middle to keep her from escaping, but Susie broke the chain and ran off, never to be seen again.

'Jocko' sets out to see the countryside

Jocko, one of the Rocky Point escapees, “was quite a rascal, stealing pies which were cooling from windowsills, breaking into houses and ruining gardens in the area,” Frank Ginaitt of Warwick told The Journal years later. But Harriette Geddes defended the monkey's honor. “Jocko did not take any pies from my windowsill, but one day he entered my pantry and got into the bread box,” she admitted.

In November 1940, Jocko wandered the countryside, with sightings throughout Warwick, and even in the downtown of neighboring East Greenwich. Jocko always kept a step ahead of the authorities, who had been summoned whenever the monkey frightened a resident.

More: How Jocko got his name He wasn't the only one: Why more than a few monkeys are named Jocko

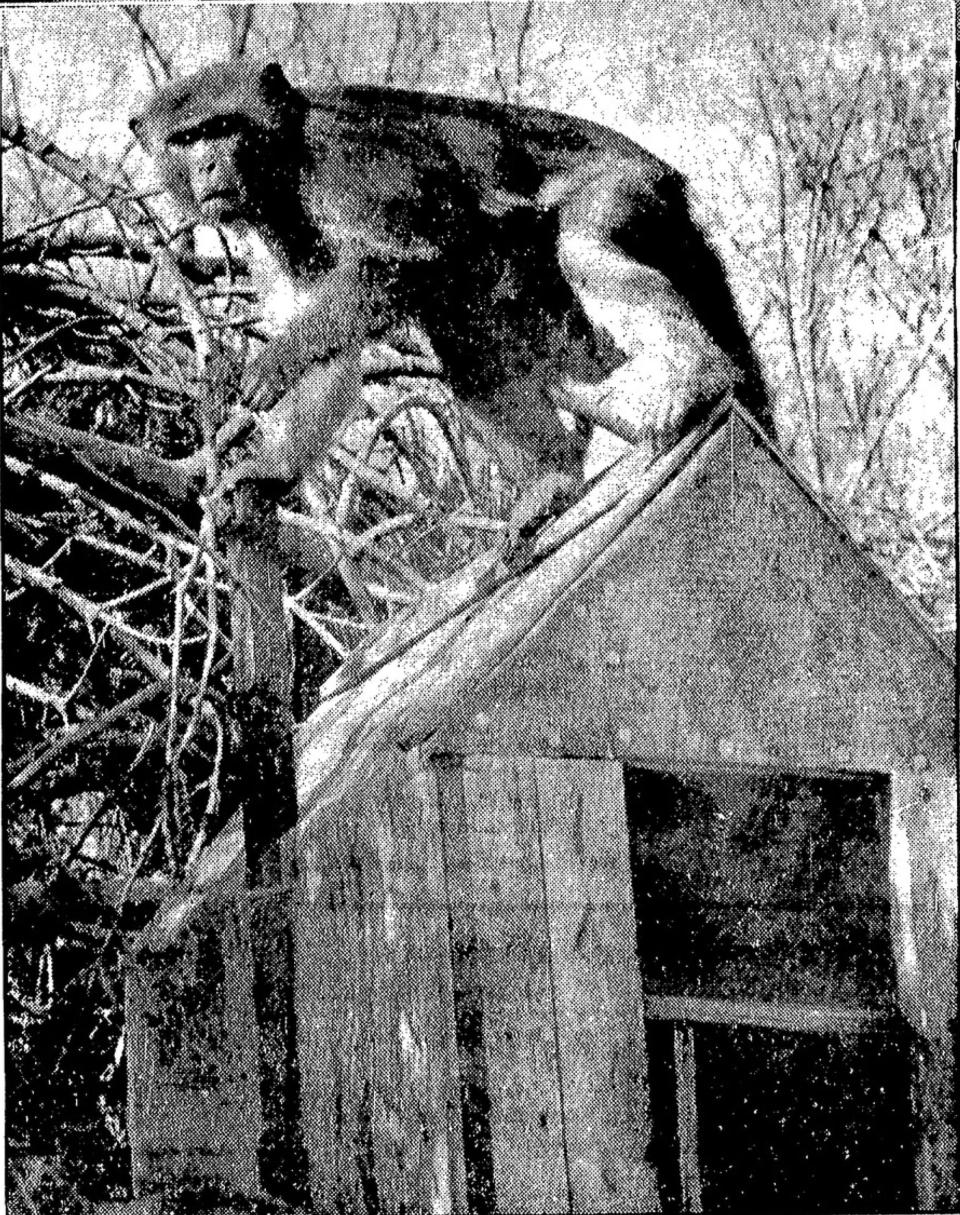

On Nov. 13, Jocko climbed into a third-story bedroom window of the girls' dormitory at East Greenwich Academy, a private boarding school.

Most students were at chapel, leaving math teacher Edna Ash alone in the dorm when Jocko burst through the window. The startled woman quickly spread the alarm while Jocko scampered up to the roof of the dorm. As students exited the chapel and flooded the campus, Jocko was seen surveying the crowd from the rooftop before running off toward St. Luke's Episcopal Church.

Local and state police, joined by armed residents, took up the hunt. Police Chief Harold Benson ordered the monkey shot on sight.

Sightings over the next few days raised hopes among his fans that Jocko was heading back to Rocky Point. He was spotted in the Lincoln Park section of Warwick, and then in Conimicut.

On Nov. 23, The Providence Journal reported from Dudley Avenue, about two miles from Jocko's Rocky Point home. The monkey had crawled into the cellar of a vacant summer cottage, been shot with a .22-caliber bullet and was found dead in the cellar, with no explanation of who had shot him.

Recalling the past couple of weeks of residents' frightening encounters with Jocko, Warwick Dog Officer Edgar H. Luther expressed relief to hear of the monkey's death.

Monkey sightings last for years

Although Jocko's story ended in that Warwick basement, the Rocky Point monkeys lived on, at least in the public's imagination.

The spring, summer and fall of 1943 brought a rash of monkey sightings in southern parts of the state attributed to the Rocky Point monkeys, with neither proof of a connection nor much evidence of actual monkeys.

In June a monkey was said to be raiding vegetables from World War II Victory Gardens in parts of Warwick. Twice, at different locations, a police officer was said to have treed a monkey, but each time the animal disappeared without a trace.

In July, monkeys were reported to be hanging around the outskirts of the North Kingstown village of Wickford.

In August, as reports came in from Charlestown, Richmond, South Kingstown, Narragansett and North Kingstown, armed residents organized a monkey hunt near the Carolina Mill, but no simians were spotted.

By September, monkey hunts had become a pastime in Narragansett, where the police had been notified repeatedly that monkeys were on the loose throughout the town.

"The latest report placed a monkey on the Kingston road near the ball field. Residents there observed an animal in a tree placidly eating apples," The Evening Bulletin reported on Sept. 23. "Police find the creatures rather elusive. By the time they arrive at places where the monkeys have been reported, the animals have invariably disappeared."

And, just like that, newspaper reports of the Rocky Point monkeys also disappeared, and the Rocky Point monkeys faded into the history books.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Escaped monkeys wrought havoc when they roamed free in Warwick