As immigration sweeps spread fear, activists and sheriffs unite to protect neighbors

GREENSBORO, N.C. — How do you spot an ICE agent in your neighborhood?

“They dress in plain clothes, never wear uniforms,” community organizer Laura Garduño Garcia told the two dozen attendees, mostly women and a few men and children, who sat attentively in a semicircle of folding chairs in the multipurpose room of a Quaker meetinghouse in Greensboro, N.C., on a recent Saturday.

“We know they drive American cars, and we know most raids take place before 9 a.m.,” said Andrew Willis Garces, director of organizing and communications for Siembra NC, a North Carolina-based project of the American Friends Service Committee established in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election.

For nearly two hours, Willis Garces and Garduño Garcia took turns leading the conversation in Spanish, explaining to the group of primarily undocumented Greensboro residents their basic legal rights; the tactics U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has been using to round up undocumented immigrants within their community; and how to avoid getting caught. While most in attendance were already members of Siembra (which means “sowing,” as in seeds), about eight stood up at the start of the meeting to identify themselves as first-timers.

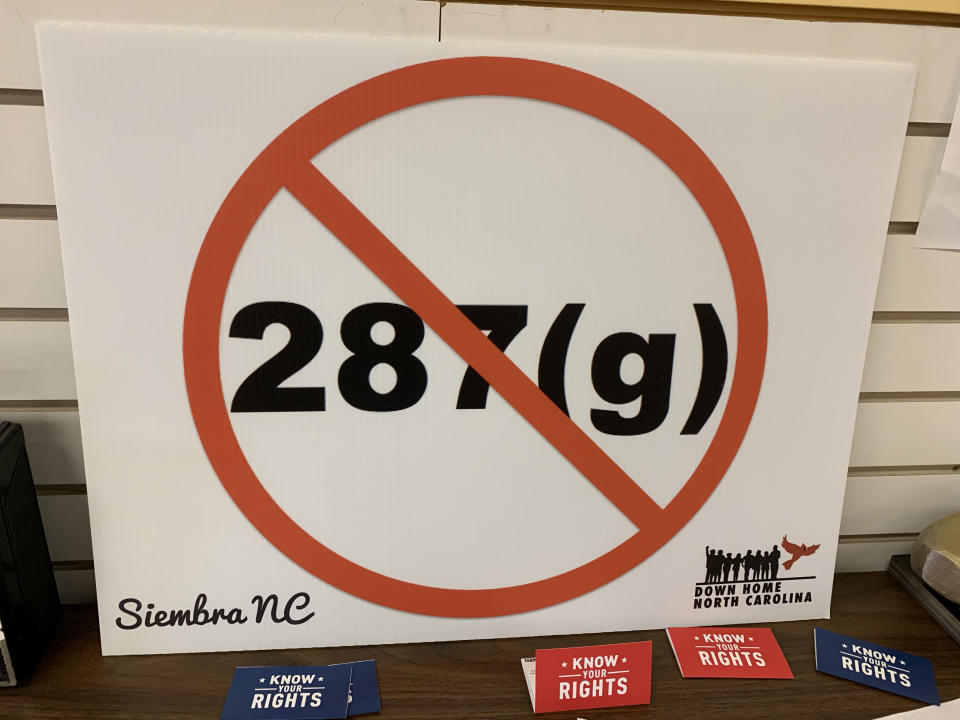

ICE’s increasingly aggressive actions over the last two years have been met with this form of nonviolent resistance from grassroots groups like Siembra, which has established itself among the communities of North Carolina’s Alamance, Randolph, Forsythe and Guilford counties. In addition to efforts to organize and educate undocumented residents on the ways they can protect themselves and their neighbors against ICE, Siembra also is urging sheriffs in these counties to follow the example of their newly elected counterparts in the nearby counties of Mecklenburg, Wake and Durham who have ended long-standing agreements to cooperate with ICE by, among other things, holding undocumented immigrants in local jails on the agency’s behalf.

Though popular in the communities, these moves prompted a backlash from federal immigration officials, who say they were forced to step up enforcement, including a four-day operation in February that resulted in the detention of 200 undocumented immigrants from across North Carolina.

At a press conference, Sean Gallagher, director of ICE’s Atlanta field office, said the February raids were necessitated by some sheriffs’ “dangerous policies” and warned that those counties should expect increased ICE presence as the “new normal.”

Gallagher’s comments reflect a national trend toward large-scale enforcement operations by ICE over the last two years, especially in localities with so-called sanctuary policies that prohibit or discourage local law enforcement agencies from certain forms of cooperation with federal immigration enforcement.

Although Gallagher, whose office covers Georgia and the Carolinas, singled out counties where sheriffs were declining to cooperate with ICE, the agency has been conducting large-scale enforcement operations across the state. The February raids had a chilling effect on North Carolina’s immigrant communities, bringing normal life to a virtual halt for days. As families scrambled to locate relatives who, they discovered, had been moved to an ICE detention facility in Georgia — many parents kept their children home from school. Then, in the days and weeks that followed, amid a dizzying swirl of rumors and factual reports of additional arrests in other parts of the state, many continued to stay indoors, seldom leaving home except for school or work. Activities like shopping and eating out were now viewed as dangerous. Social gatherings suddenly seemed risky, causing some to cancel even major events, such as baby showers or quinceañeras, the traditional Latin American celebration of a girl’s 15th birthday. Businesses suffered.

“It paralyzes us,” said one woman at the Siembra meeting, as the conversation turned to the spread of rumors on Facebook about supposed ICE activity. Many in the group nodded in agreement as she and others described hours of self-imposed house arrest because of an unsubstantiated Facebook post claiming ICE agents had been spotted in the parking lot of a Walmart or near a housing complex.

“ICE, I think, has two forms of controlling us,” another woman told the group. “One is through detentions, which we are always thinking about, but the other is [by scaring] the people.”

Hence Siembra’s mission to provide reliable information about ICE tactics, helping immigrants reclaim some control over their own lives, sending volunteers door to door in their own neighborhoods, handing out information about ICE, immigrants’ legal rights and how to report suspected ICE activity to a 24-hour hotline. An unfamiliar car with tinted windows, parked at the entry to a trailer park whose residents are largely undocumented, might prompt a tip. Trained volunteer “verifiers” are then dispatched to ascertain if ICE is conducting an operation.

If ICE activity is confirmed, Siembra spreads the word on one of its 10 or so WhatsApp groups, organized by zip code, with hundreds of people in each, warning them to be cautious about going outdoors. Siembra verifiers stream real-time interactions with ICE agents on Facebook Live, using the platform to remind viewers of their rights.

“We want people to feel empowered and powerful, not anxious and afraid. and that they can train other people on that same thing and think, We are not just resilient but we are powerful,” said Willis Garces.

During the first week of February, Willis Garces said, “we got 680 phone calls in a 5-day period.” In a typical week, he estimated that the hotline receives between two and 12 calls per day, the majority of which appear to be false alarms.

For anyone residing in the country illegally, the fear of deportation is a constant that predates President Trump and will continue after he’s left office. The president with the largest number of deportations during his administration was Barack Obama. But while his administration targeted specific categories of undocumented immigrants, prioritizing criminals and repeat border crossers, particularly during its last two years, the current administration’s approach to interior immigration enforcement seems less defined by specific policies than by aggressive, wide-ranging and seemingly indiscriminate roundups.

Perhaps one of the best indications of the agency’s approach to interior enforcement under Trump came from then Acting ICE Director Thomas Homan during a June 2017 appearance before the House appropriations subcommittee, in which he spelled out the implications of then Secretary of the Department of Homeland Services John Kelly’s earlier memo officially dismantling the enforcement priority categories established under President Obama. Homan said the agency would still prioritize deportation for national security threats, convicted criminals, people caught reentering the country illegally after previous deportation and those with final orders of removal. But, he said, “If you’re in this country illegally and you committed a crime by being in this country, you should be uncomfortable, you should look over your shoulder. “You need to be worried. No population is off the table.”

Across the country, ICE arrests of immigrants without criminal convictions have skyrocketed under President Trump, more than tripling during the first 14 months of his presidency, according to ICE data initially reported by NBC News in August.

Among the ways the Trump administration has sought to carry out this general mission, including multiple ill-fated attempts by former Attorney General Jeff Sessions to withhold federal funding from sanctuary jurisdictions, is by expanding its partnerships with local law enforcement agencies through a program known as 287(g).

Garry McFadden made clear that this mission did not align with his during his campaign last fall for sheriff of Mecklenburg County, which includes North Carolina’s most populous city, Charlotte. Among the changes he promised was to end of the department’s participation in 287(g), under which sheriff’s deputies were required to run information on all inmates booked at the county jail through a federal database. If they appeared to be in the country illegally, the sheriff’s office would notify ICE and continue to detain them for federal agents to take into custody.

In his first official act as sheriff, McFadden followed through on this campaign promise with a public celebration at Hispanic-owned Manola’s Bakery in Charlotte, marking the end of the 287(g) era in Mecklenburg County.

McFadden acknowledges he “made a statement,” but the media-savvy sheriff, easily recognizable in his tailored, three-piece suit and designer shoes, insists his position on ICE “isn’t about politics.”

Instead, McFadden told Yahoo News, the decision to terminate the program was based on his own 37 years of law enforcement experience, including 22 spent as a homicide detective with the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department. Making his job even more difficult, the widespread suspicion of law enforcement in some minority communities that made victims and witnesses reluctant to come forward was compounded by the fear of becoming entangled with ICE.

“It was eroding trust,” McFadden said of the program. “It creates an environment for violent criminals to operate freely in [immigrant] communities because they know victims are afraid” to call police or testify in court.

“You are helping to breed violence, because you are allowing these things to go unreported and people know that,” he said. Under his new policy, ICE is still notified when his office arrests someone who may be in the country illegally. Information about arrestees’ citizenship status or country of origin is automatically submitted to a federal database that ICE has always had access to, regardless of a county’s participation in 287(g). But unless it receives a criminal arrest warrant for a specific person in custody, McFadden’s office is no longer obligated to report that person directly to ICE, or to continue holding him or her on ICE’s request for investigation of a possible immigration violation.

Now, sheriff’s deputies will no longer carry out ICE duties, such as questioning inmates about their immigration status to determine if they are in the country illegally, nor will an ICE agent be stationed inside the Mecklenburg County jail.

“This is a voluntary agreement, it’s not the law,” McFadden said of 287(g), adding that he viewed the February raids as retaliatory. “They ask us to play with them and when you don’t play with them, they become a bully.”

In response to McFadden’s public breakup with ICE, Gallagher, the Atlanta field office director, called the new sheriff’s action “an open invitation to aliens who commit criminal offenses that Mecklenburg County is now a safe haven for persons seeking to evade federal authorities.”

In a statement to Yahoo News, Bryan Cox, spokesman for ICE’s southern region, referred to that same comment, as well as other warnings he and Gallagher both issued against McFadden’s pledge to end 287(g) in his election campaign. Claims of retaliation by ICE, Cox said, are “completely baseless, as this agency was on record multiple times last year making clear in advance that should these policies be implemented, ICE would have no choice but to reallocate its enforcement resources if no longer allowed access to the county jail, and that such a policy would likely result in more persons being encountered by ICE, not less.”

For McFadden, ending 287(g) was simply a necessary step toward rebuilding trust between his office and the immigrant community.

“I have to still protect these people, documented or undocumented,” said McFadden. “If an undocumented person is raped, robbed or killed, I can’t say ‘We don’t investigate that because they’re undocumented.’ So, I have to build a relationship.”

McFadden repeated this same message following a recent Sunday mass at Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church, eliciting resounding applause from some 500 people who filled every seat in the chapel, stood against the walls and spilled out into the front entrance of the church, lining up to shake hands, take selfies and above all express their gratitude to the new sheriff.

“People [are] really, really excited about his stance regarding ICE,” said Father Hugo Medellin, associate pastor at the church, whose large congregation is made up mostly of Hispanic immigrants. “As soon as we mentioned he was coming, the place was going to be completely overcrowded and it was going to be chaotic.”

“We don’t know how to thank him,” said Marlene Serafin Silva, who volunteers in the kitchen at Our Lady of Guadalupe. “We feel more secure with him.”

Silva was born in the capital of Mexico and has lived in the United States for 50 years, half that time in Charlotte. She was one of the first people to approach McFadden following his recent unannounced appearance at the church and she stuck close to his side as the sheriff made his way from the chapel to the kitchen, where he was greeted by more fans.

“The people are scared, you know. That’s why we’re feeling good now,” said Arevinar Cruz after he and his son, 9-year-old Alex, had their turn posing for a photo with McFadden. Cruz, a native of El Salvador, has lived in the U.S. for almost 19 years under the Temporary Protected Status program, which permits foreign nationals of certain countries impacted by armed conflict or natural disasters to live and work in the United States for designated periods. He belongs to a local alliance of TPS holders seeking legal permanent residency. Though he said he has always trusted the police, Cruz was excited about the prospect of scheduling an appointment with the sheriff to discuss his organization’s efforts — something he “never ever” imagined doing with any of McFadden’s predecessors.

The recent ICE operations in North Carolina are not unique, but reflective a number of larger national trends seen in similar sweeps targeting immigrant communities over the past two years — particularly in sanctuary cities like Chicago, Los Angeles and New York.

Unlike traditional worksite raids, these community-based operations have been carried out through traffic stops and other seemingly random encounters with plainsclothes agents in unmarked cars. They’ve also been marked by notably high numbers of what ICE refers to as “collateral” or “at large” arrests of undocumented immigrants not actually targeted by ICE but, as Gallagher put it during his press conference on the North Carolina raids, were just “in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Collateral arrests of people encountered during targeted ICE operations are not new. However, the sheer volume over the last two years, comprising more than half the total number of people caught in some of these larger community sweeps, have raised concerns among immigration advocates about who, exactly, ICE is targeting with these operations, and the legality of their methods. Most people ensnared by such “collateral” arrests do not have criminal records.

Mark Fleming, associate director of litigation for the National Immigrant Justice Center, described operations in which ICE is “literally going into Hispanic neighborhoods in Chicago where they believed there would be undocumented immigrants and pulling people over with no basis, to identify whether they were unlawfully in the U.S.”

Last May, the NIJC filed a class-action lawsuit, accusing ICE of using “warrantless traffic stops and racial profiling, among other tactics,” to conduct more than 100 “collateral” arrests over the course of six days in Chicago — 68 percent of the total 156 people caught up in that particular operation.

In the complaint, initially filed on behalf of two longtime Chicago residents arrested in that sweep, NIJC noted that language in ICE’s press release announcing results of the Chicago operation echoed those released following similar actions in Los Angeles, New York, Northern California and Philadelphia. Like Gallagher’s comments following the North Carolina raids (in which a third of the 200 arrests were deemed collateral), ICE’s press releases also seemed to blame those cities’ policies for forcing ICE to take its enforcement to the streets.

ICE maintains that sanctuary laws or other policies that limit ICE’s ability to utilize local law enforcement resources are a threat to public safety. In reality, Fleming argues, such policies simply make it harder for ICE to apprehend a broad array of people.

“The reality is they know they will have to use their resources only to go after people who have very serious crimes, they don’t want to do that,” said Fleming. “That piece is what ICE sees as undermining their mission, which is to deport as many people who are here unlawfully as they possibly can.”

Asked how racial profiling and other sorts of unlawful tactics can be avoided when conducting such large numbers of collateral or at-large arrests, an ICE spokesperson told Yahoo News that “pursuant to longstanding policy… officers regularly assigned to conduct at-large law enforcement field operations complete Fourth Amendment training, at a minimum, every six months. In addition, all [enforcement and removal operations] law enforcement officers assigned to participate in a nationwide law enforcement operation involving at-large targets complete Fourth Amendment training prior to participating in that operation.”

The spokesperson also noted that recent statistics released by ICE show that collateral arrests have decreased during the first quarter of 2019 compared to the same time last year. However, ICE does not attribute that drop to changes in its interior enforcement strategy but, according to Nathalie Asher, ICE’s acting executive associate director for enforcement and removal operation, it is the result of shifting resources to respond to increased demand for detention of people arriving at the southwest border.

Sheriffs like McFadden show no signs of giving in to pressure to cooperate with the agency. In fact, days after the big February raids, another newly elected sheriff, Bobby Kimbrough of Forsyth County, announced that he would terminate his office’s prior agreement to detain people suspected of being in the country illegally on ICE’s behalf at the county jail.

“We will not be an extension of ICE, doing roundups [and] immigrant investigations,” Kimbrough said at a news conference. Now, Siembra is determined to get the new sheriff of Guilford County, which includes Greensboro, to follow suit.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: