Hiroshima visit provides a timely history lesson | Along the Way

Now 92 years old, Kikyomi Kouno recalled a local train trip with her mother 79 years ago from their home, 22 miles outside of Hiroshima, to search for her two sisters in the city that had been hit with the first ever atomic bomb used in combat.

The train stopped outside the city, so she and her mother had to continue on a rice path. Hiroshima, a city of 345,000 people, was gone. Much of it had been vaporized.

They kept walking, the stench of decomposing, burned bodies fouling the air. A few still alive pleaded for help, their clothes burned off their bodies. For others, their skin was hanging from their bodies.

At the Red Cross Hospital, the women learned Kikyomi’s sister, a nurse, had been saved and taken for treatment to another hospital. They continued on, searching for her other sister.

Kikyomi noticed the bodies piled up near the hospital were teenagers her own age.

The two women walked south across Mijukibashi Bridge into Ujina, a suburb where Kikyomi’s sister lived. Though the river below was filled with corpses, the women continued on to find Kikyomi’s sister – and her house – safe.

In the years since then, Kikyoma has lost her mother and sisters at young ages, perhaps the result of radiation produced by the atomic bomb.

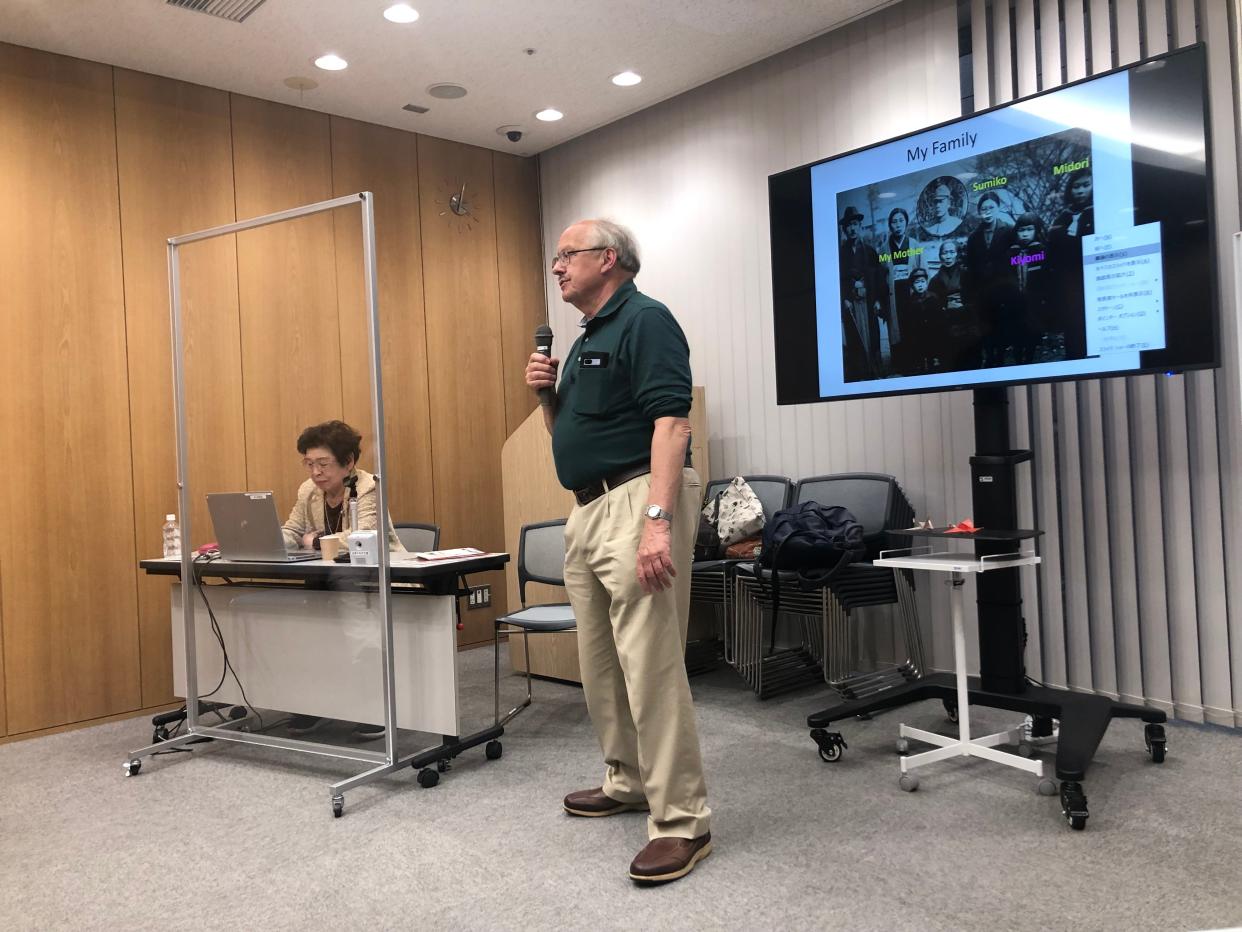

Such was the story our group of 20 Americans and Canadians on a Road Scholar Japan tour heard last week at the Peace Memorial Museum in downtown Hiroshima. Today, nearly 80 years later, Hiroshima has been entirely rebuilt.

A beautifully landscaped, 30-acre park at the center of town commemorates the bombing.

During our 2½-week tour of Japan, during Cherry Blossom season no less, our group visited beautifully maintained Buddhist and Shinto shrines, and other sites in major population centers like Tokyo, Kyoto, Hiroshima and Osaka.

We spent two nights in a traditional retreat in lush Kashikojima Park on Ago Bay, where Japan in 2014 hosted a G7 conference.

Our son Chris, an experienced Japan traveler, added to our group tour by leading Janet and me, and Bob Heath and Beth Buchannan, also of Portage County, to Nikko and Hakone, two exquisite destinations in mountains beyond Tokyo.

For a finale, he led the four of us to Koyosan, a historic Buddhist temple site on a mountainous peninsula outside Osaka. Bob and Beth, both retired biologists, contributed much to our group’s comprehension as we walked through Japan’s incredible gardens and parks – three of them Bonsai gardens – and encountered trees and other foliage abundant in Japan, but some rarely found in America.

Hearing Kikyomi’s talk at Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Park and Museum was the most profound undertaking of our tour.

She was a powerful reminder and warning about the genie of nuclear war that has been bottled up since World War II. Our tour leader, New Zealander John Hundleby, who translated, shook his head as Kikyomi pleaded for world peace and the abolition of atomic weapons. Hundleby referred us to Vladmir Putin’s warnings that he might use nuclear weapons in Ukraine, to the possession of nuclear weapons by North Korea, and to the volatile Middle East, and the war in Gaza.

Kikyomi said as a youngster during World War II she learned to hate Americans. She said children in her community were armed with pointed sticks and taught to use them if American invaders threatened them.

“We were all prepared to die for our country,” she said.

Gradually, she said, she found there is more than one side to any story. As a Hiroshima survivor and speaker for world peace, she was invited to the United States. Stopping in Hawaii, she visited the Pearl Harbor site and saw the memorial dedicated to those who died during Japan’s surprise attack on the United States on Dec. 7, 1941. That and the kindness with which she was treated in the United States softened and broadened her outlook, she said.

The Peace Museum’s exhibits show the devastation of a single atomic bomb. Prepare to feel disturbed if you visit. It instantly killed 70,000 people, and the death toll climbed to 140,000 within four months. Among those who perished were some 20,000 Koreans brought to Japan as laborers, and 12 Americans held in Hiroshima as prisoners of war.

Curiously, the skeleton of a domed Hiroshima industrial exhibition hall remained and those planning the 30-acre memorial park in downtown Hiroshima left it standing as a ghostly warning. The names of those who died are kept in a vault near a memorial pond. Unidentifiable remains are buried in a mound in the park. A hanging sculpture with figures of playful, fun-loving youngsters attached reminds us that many of the victims were innocent children.

The Academy Award winning film “Oppenheimer” accurately shows the ambiguity the physicist felt in having directed the creation of the atomic bomb during World War II. Pleased the bomb succeeded in ending World War II, Oppenheimer regretted the pain the bomb had delivered, mostly to innocent, unsuspecting civilians who just happened to be living in Hiroshima during World War II. He dreaded that his work had moved humanity closer to building a doomsday weapon.

In the decades since, Japan’s hard-working, disciplined and well-educated people have turned their country into one of the world’s wealthiest nations. Hiroshima and its people have moved on. Their Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park warns us that we entered a more dangerous age with the dropping of an atomic bomb Aug. 6, 1945.

David E. Dix is a retired Record-Courier publisher.

This article originally appeared on The Alliance Review: Visit to Hiroshima offers timely history lesson