How Fox News host Bill Hemmer conquered the Arctic

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It started with a call from the US Navy back in November, asking if I’d be interested in taking a trip to the Arctic later that winter.

It’d be part of a three-week operation in the Arctic Ocean in March called Operation Ice Camp, which has happened every two years since 1946.

It involves scientific research, evaluating military operational capabilities in the region, and the security of our nation.

They don’t usually bring along civilians, I was told, but they wanted me to tag along to see what actually goes on during these operations.

“I’m intrigued,” I said. “Tell me more.”

They told me I’d be flying to the northern slope of Alaska, right next to the Arctic Ocean, where I’d meet with several dozen sailors and scientists, and spend a few days (and nights) watching them at work.

Then we’d get on a helicopter, which would take us to an active ice floe — a large free-floating mass of ice on the open water, specifically the Beaufort Sea — and meet up with a US nuclear submarine, which would have to break through the ice so we can board, and then descend into the chilly depths, 180 feet below the ice.

I considered it for a minute, and then said, “Fantastic. I’m in.”

I couldn’t possibly turn it down.

If you asked me to come up with the ultimate fantasy adventure trip, I never could have even imagined this one.

The experience — which we documented in the new TV special “Battle for the Arctic with Bill Hemmer,” now streaming on Fox Nation — was a new one for me.

It took almost eight hours to fly from Washington, DC, to northern Alaska, and when you cross the Yukon, it’s almost exclusively ice and snow as far as the eye can see.

By the time we got to Deadhorse, Alaska, an oil town that more than lives up to its name, you can’t tell where the Arctic Ocean ends and the land begins.

My only thought was, “Sir, can you please turn this plane around? Because nothing can live down there.”

When we touched down on that ice, it was probably the softest landing I’ve ever felt.

It was like hitting a pillow.

And then the door flew open and we felt the first blast of arctic cold on our faces.

You can’t really prepare yourself for Alaskan cold, especially in Deadhorse, where the temperatures can get as low as 50 below zero, with a real feel of 88 below.

(No, I’m not kidding.)

I’m no newbie when it comes to frigid temperatures.

I was in the crowd for the 1981 “Freezer Bowl,” the coldest football game ever played, between the Cincinnati Bengals and San Diego Chargers.

(It was so cold, some claimed, a hot chocolate from the concession stand would turn into a milkshake.)

But those frigid temps were nothing compared to the Arctic.

The difference is, there’s no place in Alaska to hide from the cold, especially at the Ice Camp.

When those skin-cracking winds start blowing, you can’t avoid them.

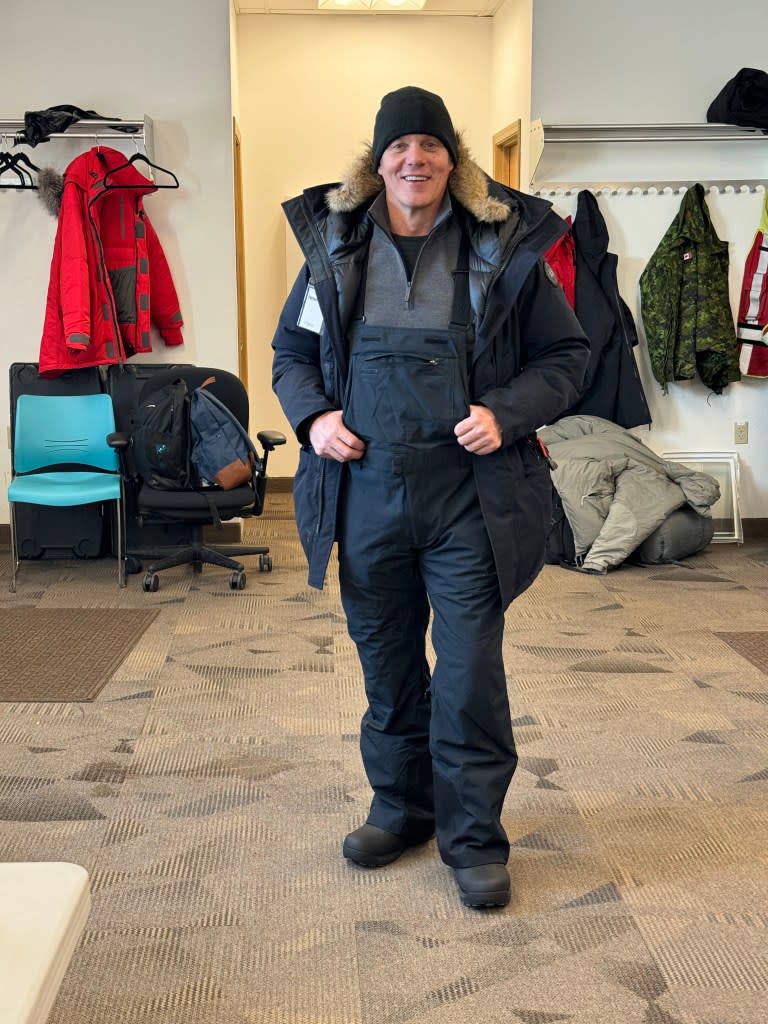

We did a pretty good job with clothing prep.

Except for boots.

My boots were absolutely not effective.

My right toe was numb for about a month after we returned.

And we were only there for three days.

I have no idea how these scientists stay there for five full weeks.

The other concern was polar bears.

They weren’t exactly an imminent threat, but polar bears do occasionally wander through, enough that there were monitors keeping a close watch for furry intruders, and rifles in every tent, just in case you needed to fire a warning shot.

I wasn’t exactly looking over my shoulder, but it was one more thing at the back of my mind.

The day-to-day operations at Ice Camp spanned everything from military drills — communicating with submarines or aircraft — to scientific research.

In one of the tents, they’d drilled massive holes in the ice, as part of ongoing studies on water temperature and how (and when) the ice is melting.

It’s a fascinating topic, especially when you talk to the scientists directly involved in climate science.

The White House has suggested that the Arctic’s summer ice will be completely melted by the year 2030, but when I mentioned this to one of the Ice Camp scientists, a researcher from the University of Alaska Fairbanks who’s been studying climate science for almost three decades, he believes that estimate is “way too fast.”

This year’s operation has extra significance, mostly because of increased geopolitical tensions in the region.

There are eight nations with territory in the Arctic and seven belong to NATO.

The other is Russia.

There is an estimated $1 trillion in minerals in the region, and Arctic warming means there are more opportunities to mine them.

Admiral Daryl Caudle, who’s been the 35th commander of United States Fleet Forces Command since 2021, told me that Russia’s ability to mine those minerals is (at the moment) minimal.

But what about 20 years from now, or 40 years?

That’s what concerns him.

And then there’s China, which declared itself a “near-Arctic state” in 2018.

There’s no part of China that physically touches the Arctic Circle, but the country has struck up a relationship with Norwegian businesses and opened a science lab north of the Arctic Circle.

Why would they do that?

The Chinese are very invested in rare earth materials, and there’s a lot of that below the Arctic ice.

Right now, those are international waters, and the US, along with their allies in Britain and Canada, want to make sure they stay that way.

When I asked Caudle why the military bothered to take a nuclear submarine and burst it through the Arctic ice, he told me, “We want Moscow and Beijing to know that we can pop up anywhere.”

Speaking of that submarine, it was my next stop.

We traveled 200 miles north by helicopter to an ice floe camp to catch our ride: the USS Hampton, a 360-foot, 6,900 ton nuclear-powered sub from San Diego.

This particular ice floe had been picked after months of searching for the perfect location.

The sub needed almost exactly three feet of ice to break through.

Less than two feet wouldn’t be enough to hold the vessel in place.

My biggest concern, to be honest, was claustrophobia.

I don’t know about you, but I’d never been inside a nuclear submarine.

After they’d chipped away enough ice to open the hatch, we climbed down a ladder and into the belly of the sub, and right away you realized there wasn’t a lot of room.

The passageways —mthey didn’t call them hallways — were only 24 inches wide.

This doesn’t seem to bother the other 150 men on board.

Every one of them has an objective at all times, and they’re constantly moving.

It wasn’t just the human passengers; every last inch on that submarine has a purpose.

Nothing’s extraneous.

Caudle explained the commodity of space to me in a way that was downright poignant.

He said, “Bill, you live this big,” and he held his hands far apart, “and then you understand you’ve got to live this big,” and he held his hands closer together, “but in the end, all you really need is this,” and then he held his hands just inches from each other.

That, he said, is submarine life.

If the confined living doesn’t get you, loneliness probably will.

At least that’s what I assumed.

I was only down there for 24 hours, and it was weird to be so utterly cut off from the outside world.

A submarine has the capacity to receive and transmit some signals, but to be truly stealth, any communication is few and far between.

I remember talking to a commanding officer after we’d watched ourselves on a monitor disappear into the depths of the Arctic Ocean.

He’d just come from a 15-day trek from San Diego through the Bering Strait.

I told him, “You have no ability to look at an iPhone, to check Instagram or Facebook or any other social media. What does that feel like?”

Without missing a beat, he said, “Freedom.”

That instinct doesn’t come from the same place in every sailor.

For that commanding officer, both his father and grandfather had served on a Navy submarine.

It was part of his lineage, in his DNA.

Most of the guys on that submarine had some Naval history in their past.

The others, at least the ones I spoke with, told me that before joining the Navy, they’d felt lost.

They needed direction.

One guy told me, “I found my family on board this submarine.”

The entire trip was exhilarating, and gave me even more respect for our military.

They’re protecting us in ways, and in parts of the world, that many of us never think twice about.

Would I go back and do it again?

Would I brave the Arctic cold, and the risk of frostbite and polar bears and cracks in the ice, and being stuck inside a crowded submarine with some of the smartest, bravest men I’ve ever met?

Sure.

But next time, I’m bringing warmer boots.

Bill Hemmer’s new series, “Battle for the Arctic,” is now streaming on Fox Nation. This story was adapted from an interview between Hemmer and Eric Spitznagel.