Foundations give big boosts to some Knox County schools, but others are left behind

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Some public schools in Knox County have digital sign boards, extra STEM programs and better playgrounds paid for by generous donor organizations. Some taxpayer-funded public schools don't.

The key word: “some.”

Not all district schools have the good fortune of being backed by foundations and parent-teachers groups that funnel money directly to enhance the educational experience for students at select schools.

The nonprofits in wealthier neighborhoods can bring in hundreds of thousands of dollars each year, and organizers decide how the money should be spent. In some cases, year after year, they give enough to cover the costs of academic programs and facilities upgrades at their child's school. At Shannondale and Sequoyah elementary schools, for instance, foundations pay for science and technology teachers.

Board of Education policy allows for positions to be paid for outside the regular budget if the money is raised by foundations, parent-teacher groups or "other third parties." Teachers or staff whose salaries are funded by foundations are subject to the same employment conditions as all other district employees.

The students at those schools, in turn, gain an advantage. For kids born to wealthier parents, they're the beneficiaries of extra support their peers don't receive ‒ on top of the advantages inherent in their family situations and neighborhoods.

It's a complicated maze. While in theory all public schools should offer the same opportunities, it doesn't always play out that way.

The absence of these extras means teachers and administrators are left scrambling for resources and writing grant proposals to outside organizations for big-ticket items that other schools receive from their foundations.

Twenty-two schools out of 91 have foundations. Most others have some form of support organizations − a band booster club or parent-teacher group.

The schools that don’t have nonprofit foundations aren't totally on their own. They receive financial support from the Knox Ed Foundation and the United Way's Community Schools program. But these programs serve multiple schools and provide no direct parent-to-school pipeline for funds like a school-specific foundation does.

What do foundations bring to the table?

The foundation supporting West Hills Elementary School raised money to build an outdoor learning space, complete with benches and a cover to protect from the elements. The classroom is painted blue and golden yellow, the school's colors. West Hill's playground has well-manicured artificial turf and it's fully accessible for students with disabilities.

Foundations also pay for outdoor classrooms at some schools, providing teachers and students with an inviting alternative for learning.

“Having the funds to make outdoor classrooms makes a difference,” said Samantha Singh, whose kids go to Northwest Middle and Pleasant Ridge Elementary schools.Both schools have parent-teacher groups, but not a foundation. “When you have extra money to build something (like outdoor classrooms), it makes a difference in how kids perceive their learning environment.”

Northwest Middle School on Pleasant Ridge Road is a diverse school with 32% Black and 36% Hispanic students. The school’s enrollment is a little over 750, and 39% come from economically disadvantaged backgrounds and 16% of students have disabilities.

Pleasant Ridge Elementary also is a diverse school, with 24% Black and 19% Hispanic students. The school has 281 students and 23% come from economically disadvantaged backgrounds.

The schools scored D (Pleasant Ridge) and F (Northwest Middle) in Tennessee's first-ever grading of each public school. The grading system has been a subject of controversy since its inception, with teachers and lawmakers divided on whether the grades accurately reflect how a school is performing.

Critics argue the grades unfairly ignore the socioeconomic conditions of a school's community.

Four of Knox County’s 91 Schools received an F grade and 19 scored a perfect A. Of the 19 that received an A grade, six are supported by either a foundation or both a foundation and a parent-teacher group.

Of the four that received an F grade, only one − Austin-East Magnet High School − has a foundation.

“If you want to have an equitable district, especially with some older schools that are in rural areas, you have to find a way to give equal opportunities,” Singh said. At her children’s schools, technology is outdated and there’s maintenance issues, she added.

She sees the difference at schools backed by foundations: “They’re cleaner. Technology is improved. Things look new. Everything looks new.”

At Shannondale Elementary School, about 10 miles away from Pleasant Ridge, a science, technology, engineering and math program helps students as young as 5 learn the ins-and-outs of critical thinking. The curriculum is designed to give them a leg up on their peers.

The STEM teacher's $45,000 annual salary is paid by the foundation, said Kevin Cole, who helps runs the foundation. The teacher worked to secure a grant last year to get 3D printers for the school, he told Knox News.

Cole is a civil engineer, and knows the value of teaching young kids STEM skills.

Shannondale's STEM teacher is experienced and is “very comfortable with kids of all age groups,” Cole said. “If she’s doing floating paper boats with paper clips and pennies in K-2, she’s building a real boat in grades 3-5. But the kids go home and they talk about the same project from a different aspect."

Cole said he sees the STEM program as a must-have. Shannondale students exposed to STEM perform better on middle school tests.

If families had to bear the cost of the STEM program, per his calculation, it would cost about $125 per student annually. With some families sending multiple kids to the school, that would be out of reach for some, Cole said.

No matter how many families choose to donate, several foundation members told Knox News, all the students at that school benefit.

“There’s no club fee,” Cole said. “We’re trying to provide it for all students.”

Should this program be paid for by the district? “We do feel that,” he said. “This is a teacher position that should be funded.”

But he sees the flip side, too.

“I do know that the budget has challenges. We all say we want the county to pay for things,” Cole said, “but I also don’t want to double my county taxes.”

Know Your Knox: How much do Farragut and Knoxville residents pay for Knox County Schools?

The city's and county’s sales tax rates are both 2.25%. Schools are funded with 72.2% of those dollars. The county has not had a tax increase in over two decades. Knox County is among the top 10 counties in the country with the lowest effective property tax rate. Growth in property tax revenue comes from new development.

A low tax rate can translate into low investment in public infrastructure, said Michael Kofoed, assistant professor of economics at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. His research expertise includes economics of education and K-12 policy.

Shannondale received an A grade from the state and was named a reward school. Reward schools score high on four indicators − achievement, growth, chronic absenteeism and English language proficiency − for K-8 schools. For high schools, college readiness and graduation rates also are taken into account.

There are huge variations even among foundations supporting individual Knox County public schools. Some have deep pockets because of a history that goes back decades, while others are modest. Tax filings help tell the story.

Sequoyah Elementary Foundation, for instance, has savings worth more than $250,000. Bearden Middle School's foundation has about $66,000 in savings.

How do foundations raise money?

Shannondale’s foundation ran a four-day virtual auction earlier this year. Items for sale were mostly experiential: fun workouts, a Christmas tree farm trip and a pass to pull the fire alarm. Craft and ice cream time with teachers also were up for bids.

The foundation raised $29,000 from its recent auction, a feat that was “several 40-hour workweeks” worth of time and effort, Cole said.

His foundation is thinking of unique ways to raise money. In the past, members organized skating events backed by corporate donors who match what members raise. It takes a lot of time and organization from volunteers who do the work on top of their jobs and child care.

“We have been able to raise about $6,000 just by skating at night,” he said.

Other schools host galas run by volunteers, basketball games between parents and teachers and school carnivals.

The schools' makeup and neighborhoods also often dictate the success of fundraising efforts.

“We can’t get donations like that in our schools that have a reputation,” Singh said. “People’s faces change when we ask for money and it’s sad to me.”

At Northwest Middle, the boys' and girls' soccer teams share uniforms. They use the American Youth Soccer Organization’s soccer field. Some middle schools, in contrast, have their own fields.

The field Northwest Middle uses doesn’t have lights, Singh told Knox News.

“If we have a game and it comes close to sunset, we have to call it,” she said.

At Bearden Middle School, the school has a running track that was newly renovated with support from the school’s foundation. Last year, the foundation raised $62,000 to pay for physical education equipment, band technology and to renovate the school’s auditorium.

The foundation, now seven years old, was founded to replace dated iPads, Principal Michael Toth told Knox News. In two weeks, the foundation had raised $80,000.

Technology needs have since changed since the district approved Chromebooks for every student in 2020 to adjust to the pandemic’s new virtual learning environment.

Who looks out for students in schools without a foundation?

The Community Schools program from the United Way is for the district's most underserved schools. Coordinators help fill gaps in communities, director Adam Fritts told Knox News.

The program serves 15 schools and will add another this year, Fritts said. It supports schools in neighborhoods that aren’t able to raise money as well as others.

“There’s always going to be discrepancies in the sheer amount of dollars we put into schools when we have people who have the capacity to raise $100,000 in one night,” he said.

While school administrators are working to address the unintended inequities, Fritts sees how history led to today's divide.

Last semester, Community Schools raised about $550,000 for the 15 schools it supports. The money goes for basics, including alleviating food insecurity, paying for school supplies and tokens of appreciation for teachers.

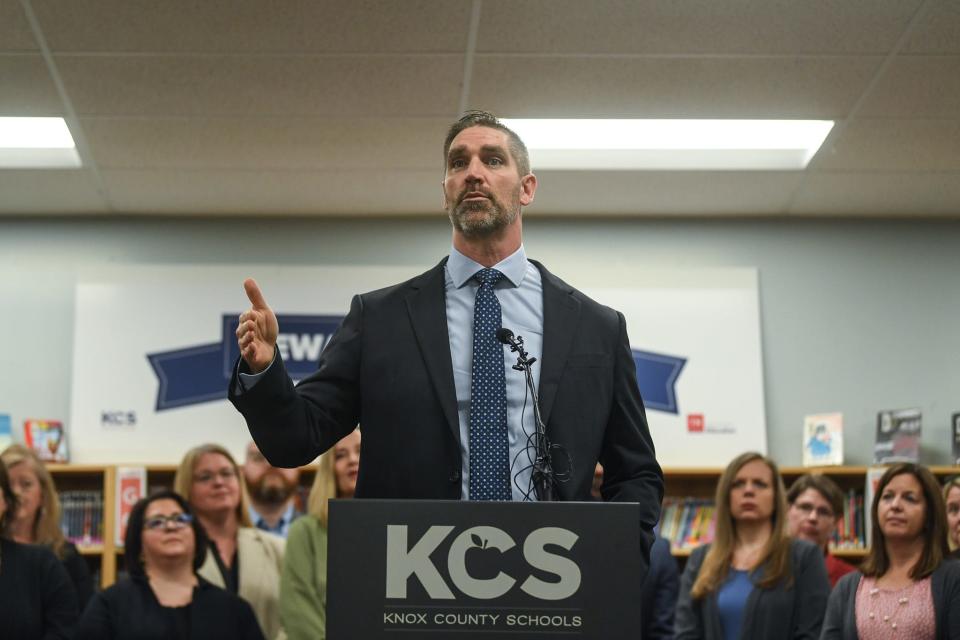

Knox Ed Foundation is another partner organization that works with the district to support schools in need. But, like Community Schools, Knox Ed supports multiple schools in the district. The foundation's leadership works closely with district leadership to make sure its work aligns with the priorities identified by Superintendent Jon Rysewyk, said Mike Taylor, Knox Ed Foundation's CEO.

Kori Lautner, the district’s assistant superintendent of strategy, sees things differently, saying there's no school that doesn't have someone looking out for it. She also makes a pitch to celebrate the uniqueness of each region and community in the district.

Some differences in the support for each school come from "recognizing that every school community is different and can benefit from different types of giving and types of support," Lautner said. "I definitely would not discount volunteer type of support as well.

“I would say that we are so fortunate in Knox County to have robust nonprofit partners in some of our highest-needs communities."

In Knox County, thanks to the “investment and interest” in public education, there’s plenty of support to go around for everyone, she added.

Federal Title 1 money is available for schools in some of the most challenged neighborhoods, Lautner said. But, those dollars come with their own set of restrictions and cannot be used to pay for digital sign boards and school beautification, for instance.

Title dollars also help pay for positions such as teachers, social workers, counselors and behavior coaches.

Austin-East Magnet High School has both a foundation and is supported by Title 1 funds. The school was "under-resourced historically," founder Matthew Best told Knox News.

Austin-East is a Region 5 school, which is the cluster of schools in downtown and adjacent communities to the east, north and northwest, including the East Knoxville, Lonsdale, Old North Knoxville and Whittle Springs neighborhoods.

The median household income for families in some Region 5 neighborhoods is as low as about $21,000 a year in comparison to about $90,000 out west between the Hardin Valley and Karns communities. The Region 5 neighborhoods also have the highest poverty rates in the county – with as much as over 30% of the population living in poverty in some zip codes. These neighborhoods also have a high rate of children living in poverty.

Administrators last year vowed to find a fix for Region 5 schools, setting goals and committing to putting all kids in those schools on a path of high achievement and engagement.

"We started the foundation to help fix the inequities," Best said. "For us it was about leveling the playing field." Best said he and his partners didn't want a "few thousand dollars to be another hurdle" for students at Austin-East.

"The Austin-East foundation is not going to fundraise like Farragut's or Hardin Valley, but we wanted to do our part and not let our kids feel left behind," he said.

More than half the student population at Austin-East comes from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, according to the latest available demographics data from the state. At Farragut High School, that number is less than 5% of the student population and 9% at Hardin Valley Academy.

If the distribution of money and resources was equitable, there would be no need for foundations, he added.

The Austin-East foundation, since its inception three years ago, has raised more than $110,000 for the school, which has been used for beautification projects and decor at events such as graduations, holidays, Black History Month celebrations, learning field trips and athletics.

Does being backed by a foundation mean better education outcomes?

Opinions are split on whether having a foundation backing a school automatically means leads to better academic outcomes. Some schools with foundations performed worse than those without in state's evaluations and district's self-imposed goals.

Christopher Candelaria, who teaches public policy and education at Vanderbilt University, said the answer is not straightforward. While more funding does mean better education outcomes, he said, it's difficult to draw a straight line between the two without granular data about the specifics of resource allocation.

"Expenditures are not perfectly correlated with the quality of education," Candelaria said. Extra money can help, but it would be a disservice to ignore other contributing factors.

"I'm not saying more money doesn't matter," he said, but the extra fundraising done by school foundations could also be a reflection of parents and neighborhoods more committed to spending time with students outside of the school setting and kids getting exposed to more funding over multiple years.

Kofoed, the UT economics professor, used a kitchen analogy to explain how funding matters for schools. From administrators to teachers and access to things like buses, every ingredient matters to long-term success as adults.

Well-funded schools and access to resources in kindergarten can have an implications on the student's collegiate career, their contribution to the labor market and so forth, he added.

In a message to parents, the Sequoyah Foundation told families it raised over $1 million for the school since it was founded in 2006. The foundation's leaders declined requests for interviews.

Several foundation volunteers devote multiple hours every month to fundraising. Sometimes, the time commitment is equivalent to having a full-time job – a luxury not available to some parents.

So why not funnel all donations into a central foundation that distributes money equally to all schools? Candelaria warns against a system that forces organizations to raise money for the district centrally versus supporting individual schools.

"Would you then see an exodus from the (public school) system," he asked. "We often think of school funding-related issues in isolation but there's an equilibrium effect."

Kofoed agrees, calling the issue of equitable distribution of resources a "classic" in policy debates about state and local public finance.

"From a public policy standpoint, I would find it very difficult to regulate private fundraising," Kofoed said. "We want to encourage parents to be involved, but how can we help areas in the county where parents are not able to be as involved?"

Smart public policy means taking a bird's-eye view, he added, and finding a way to be as close as possible to balancing returns for everyone.

Candelaria told Knox News that without more data on the direct impact of these extra opportunities on academics, it's difficult to conclude either way.

For Singh, whose children go to schools not backed by foundations, the issue is more black and white.

The district “should put more effort into making sure there is a more equitable distribution of funds. If they can’t give us more funds, they should help us access more funds,” Singh said.

Areena Arora, data and investigative reporter for Knox News, can be reached by email at areena.arora@knoxnews.com. Follow her on X, formerly known as Twitter, @AreenaArora.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: Knox County Schools foundations boost some, but others are left out