Former Autauga-Prattville Public Library director demands reinstatement

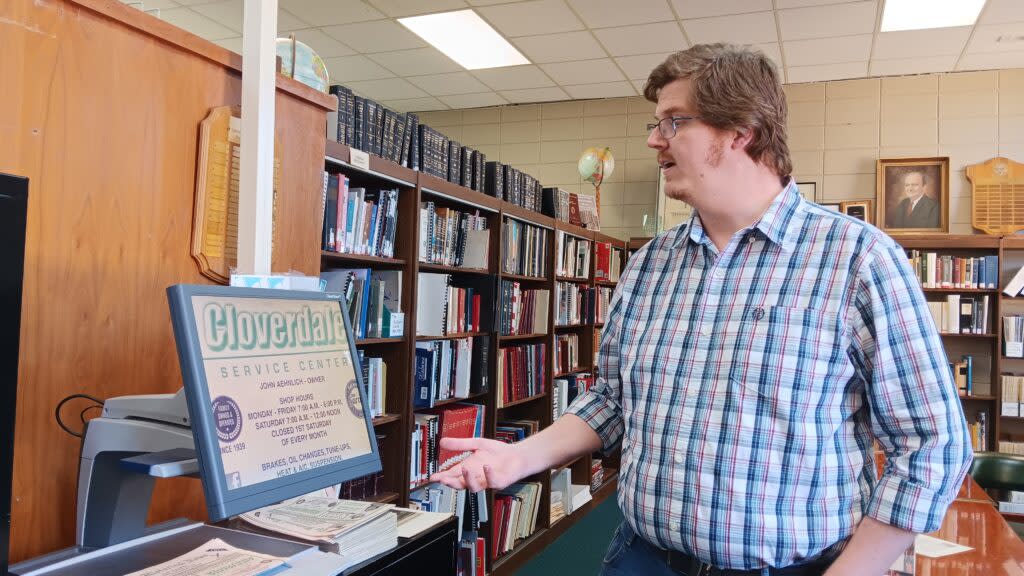

Autauga-Prattville Public Library Director Andrew Foster demonstrates how a magnifying machine works in the Alabama section of the library on Feb. 23, 2024. (Ralph Chapoco/Alabama Reflector)

The former director of the Autauga-Prattville Public Library Thursday demanded that the library’s governing board give him his job back and take action to restore his good name.

In a memo sent to members of the Autauga-Prattville Library Board of Trustees, Christopher Weller, an attorney representing Andrew Foster, accused the board of violating the state Open Meetings Act, and demanded a “retraction, correction and apology” for comments made by Ray Boles, the board chair, and Laura Clark, the attorney representing the board, for comments made about Foster to the media.

“Importantly, Mr. Foster seeks to resolve this dispute and to restore his good name and reputation in the community without the need to resort to costly and time-consuming litigation,” Weller said in the memo.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

Messages seeking comment were left with Boles and Clark on Friday.

“I love the Autauga-Prattville Public Library,” Foster said in a statement emailed to the Alabama Reflector. “Seeing the loss of staff and programming that has followed my dismissal has been heartbreaking. I’ve also watched the community reaction to it all. The actions of the past week have taken an already polarized situation here in Prattville and supercharged it. Quite a lot has been said about the situation, both in my favor and against me. I’m hoping that the recordings that I made for the purpose of protecting myself serve their purpose.”

The board fired Foster on March 14 amid an ongoing dispute in the community over content in the library and leadership.

According to Weller’s memo, Boles became hostile during a March 14 meeting and accused him of releasing confidential internal emails to the public in response to a records request from the media. Boles also said the records request should not be fulfilled because it was not in proper form.

Boles then gave Foster the option to either resign or face termination and presented Foster with the letter of resignation.

The memo says Boles also asked Foster if he was recording the conversation in executive session and Foster said he was. Boles then told Foster that recording the discussion was “a major violation of the law.” Alabama, however, is a single-party consent state, and as long as the person recording the conversation is part of the discussion, then it does not violate any law.

After consulting with his attorney, Foster told board members he would not voluntarily resign, and board members prepared to have Foster terminated.

The board convened for about 20 minutes, before gaveling back into regular session, where Boles announced Foster’s termination.

A typed statement left for the media said that Foster was terminated for “revealing confidential information to the press” and for “violation of criminal law,” which appeared handwritten on the paper. The board did not provide any evidence that Foster had violated the law.

Weller wrote in his memo that the only guidance Foster received about records requests came from the city attorney who told Foster that internal emails were not typically disclosed as part of a records request. Those communications only pertain to internal emails for possible actions taken by an agency.

Foster’s termination led to a work stoppage among some library employees and a scaling back of hours and programming at the library.

Weller alleges that board members violated the Open Meetings Act by failing to declare the reason they were going into executive session at the meeting and meeting in private to discuss Foster’s termination.

“Thus, while Mr. Foster appeared at the special meeting under the incorrect assumption that there would be a discussion regarding ‘someone’s reputation and character,’ in reality, the Board immediately confronted Mr. Foster with its predetermined decision of the termination of his employment,” the memo states.

Weller also alleged that the March 16 meeting where Tammy Bear was hired as interim director also violated the Open Meetings Act because the notice was posted less than 24 hours before the meeting was scheduled.

Foster has also demanded that Boles and Clark retract their statements made about Foster’s termination, saying they were false and defamatory.

“Since March 14, 2024 you have continued to speak to the news media about the termination of Mr. Foster’s employment,” the memo states. “Your story has changed more times than Elizabeth Taylor has changed husbands. But one fact remains consistent: falsehood.”

The memo goes on to state that Foster did not commit a criminal act. Clark did not identify what criminal law Foster violated initially, but later said that Foster violated the Open Meetings Act that included a provision for eavesdropping.

Weller wrote that Alabama is a one-party consent state and Foster did not violate the law because he was a party to the conversations. Violations are also civil and not criminal.

The road to termination

The chain of events leading to Foster’s termination began last year when a group of residents who objected to a book in the library containing inclusive pronouns formed an organization called Clean Up Prattville, part of a broader right-wing attack on library content around the country, particularly books with LGBTQ+ themes. The group was able to get the Autauga County Commission to appoint board members sympathetic to their cause.

At the board’s Feb. 8 meeting, the first one for all the new members, the board adopted a new set of policies for the library, some of which were controversial.

“For the avoidance of doubt, the library shall not purchase or otherwise acquire any material advertised for consumers ages 17 and under which contain content including, but not limited to, obscenity, sexual conduct, sexual intercourse, sexual orientation, gender identity or gender discordance,” the policy stated.

Two weeks later, according to the memo, Boles met with Foster and provided him with a document that listed 113 books within the library’s collection. Boles requested that Foster review the titles and highlight any that contained sexual content.

Foster later identified 48 books that appeared to have sexual content and 95 books that have some connection that have LGBTQ+ content. Another 8 books needed further clarification.

At a March 4 meeting, the memo says, Foster told Boles that the policy was vague. Boles spoke about tagging books with a red sticker and asked Foster if those books needed to be moved. Foster said that decision should be made at an open meeting. The memo says Boles said he did not want the books removed, just tagged, and moved to the adult section where parents could still find them.

Clark sent Foster an email on March 5 to have the books removed from the collection and not simply reshelved, telling Foster that Boles asked him to “weed out books” that violate the library’s policy.

That email also indicated that the board does not need to meet to remove books from circulation, and that either she or any member of the Board could determine whether a book violated the collection policy on a case-by-case basis.

The memo said Boles met with Foster March 8 and recommended that everyone meet to discuss the fate of the books while also admitting that he and Clark had a different perspective with respect to the books. Boles said there was disagreement among members of the board. Boles then suggested that Foster and board members meet to clarify what should be done with the books.

On March 7, Foster received an open records request and fulfilled the request, which included the March 5 email that Clark sent to Foster.

On March 11, Clark sent an email to the board and Foster indicating that any communication between her and members of the board is privileged and confidential and cannot be disclosed to the public.

“Notwithstanding the fact that there is no such prohibition, this was the first and only occasion that Mrs. Clark, or anyone else, had instructed Mr. Foster not to provide internal emails in response to open records requests,” the memo states.

On March 12, Boles sent Foster an email requesting him to post a notice for an emergency meeting that eventually resulted in Foster’s termination.

“Truthfully, I don’t know (or fully expect) that the board will reinstate me,” Foster said Friday. “This is something that I have considered quite a bit while having conversations about my options with my legal counsel. I think that if I were to be offered reinstatement, discussions would need to be had with my counsel on how I could protect myself moving forward from further action by the board. Otherwise, I would be stepping back into an at-will situation with a board that has already fired me.”

The post Former Autauga-Prattville Public Library director demands reinstatement appeared first on Alabama Reflector.