Finding the Place Between My Parents’ Immigrant Experience and My Own

James Syhabout is the owner of Hawker Fare in San Francisco, where he reimagines the Laotian food he grew up with with fiery, awesome results. His cookbook just came out and while you should come for the recipes, you should stay for the well-told story of Laotian food, his family’s history, and his journey into restaurant world. In the except below, Syhabout visits his mother’s village in Thailand for the first time.

On the outskirts of Ubon Ratchathani in Isaan— northeast Thailand— the Mun River winds like a grass snake around rice fields, forest temples, and wooden farmhouses, but the land is dry. It’s where I was born, but I didn’t really see it until I was 12.

My parents hadn’t been back home in ten years. My brother and I were old enough to travel, and my parents had saved up enough money for the plane tickets. I think my mom needed to go—badly. The minute we landed in Bangkok and she saw her youngest sister, Saun, she was in tears. Everybody was. I didn’t know what was going on.

I’d grown up with stories told by my parents about where I was from and who I was. This was supposed to be me, this country, but as we traveled north from Bangkok in a box van, which my uncle drove, I felt like we were going on safari in the most foreign place in the world. I stayed awake the whole time so I wouldn’t miss a thing.

hawker-fare-thailand-2

Photo by Eric WolfingerAfter many hours we got to Isaan, Surin province, a waypoint. It was raining, and all of a sudden the road looked like it was heaving: hundreds and hundreds of frogs were hopping across the tarmac! My uncle had to drive slowly so our wheels wouldn’t slip on smashed frogs and make us slide off the road. Moms said we’d eat frogs once we got to the village. She said they tasted like chicken. This place was strange.

We got pulled over for speeding (everybody speeds on country highways in Thailand), and I watched my uncle bribe a Thai cop to let us go. He folded bills into his hand and slid them along the top of the rolled- down window, toward the cop’s hand. I was like, Ah, dirty cops, it’s just a hustle—same as Oakland. Maybe it wasn’t so strange here after all.

We approached Moms’s village on unpaved roads in a land of clay-like orange dirt. There were fewer cars, and herds of water buffalos coming back from the fields. The house my mom grew up in, and where we stayed, was a shophouse on stilts. In front was this big platform elevated off the ground. We took naps and hung out there. That was the communal table, covered with saats (dining mats) where we ate multiple times a day, two dozen of my actual blood relatives sharing simple meals built around the work of procuring them.

One day my cousin took me out to Nong Jam Nak, the little lake the village took its name from, to watch him shoot fish with a rifle. I went out with my cousins to forage bamboo shoots—I had never seen fresh bamboo shoots before. Same thing with fresh jackfruit, longans, and lychees, fruits I knew only canned and packed in syrup, just like Dole fruit cocktail.

hawker-fare-thailand-4

Photo by Eric WolfingerWe went shrimping in the Mun River. My uncles went down with nets, dragged them through the water, and all these beautiful writhing shrimp appeared. That’s when I had my first bite of goong dten, live “dancing” shrimp. The distance between what we ate and the place we ate it was often as short as a morning’s walk in the heat.

There was an unguarded feeling I never knew in Oakland, a sense of trust. The honor system ruled at shophouses— you ordered and ate, then paid later. No one in the village locked their doors, everything sat out in the open. Everybody knew each other’s name, knew each other’s ancestors.

You bartered with your neighbors. Someone in the village was growing papaya—“Can you take him some mangoes from our tree,” my aunt yelled, “so we can have papaya salad instead?” We needed cassia leaves—“Go ask so- and- so can you pick from their tree.”

hawker-fare-thailand-3

Photo by Eric WolfingerMy mom was a different person here. I could see she felt more relaxed: wanted to go shopping early every morning, wanted to have a big party every night. She felt like she knew everything here. It made me think about how alienated she probably felt in Oakland. She was a social butterfly here in a big family, with siblings who now had kids, and she had kids, plus cousins and the whole community. I realized that’s what she was trying to build on Twenty- Fifth Street, that Lao community held together by food, the reason I had to call someone “auntie” even though we weren’t blood- related. It was like, all this shopping and foraging and cooking: It wasn’t really about getting fed. It was about tying ourselves to a world that had existed for a long, long time.

I started to get it: why we cooked for ourselves the way we did at our restaurant, the way we ate here, and why we couldn’t serve the same food to the American customers. It was different worlds, so far apart. Here it was sitting on the floor and not using utensils other than a spoon. There was no phat Thai. I didn’t have a single curry dish. Food here was so much simpler than that, like it flowed naturally out of the daily activities of my uncles and aunts in this landscape: take bones, make soup; steam vegetables; fry something, grill something; pound chile pastes and dips in the mortar that was always ready. That was the meal, three times a day, sticky rice every time. At the restaurant, we didn’t even serve sticky rice, much less any dishes that went with it.

When it rained here, the puddles in the orange dirt looked like Thai iced tea. It stayed in your clothes. Working in the family restaurant at home, grease from the woks stained my shoes. Here, the land itself turned them orange. I swear this place was trying to mark me. I got it, but it just wasn’t for me.

I did understand Moms better. Going home filled a big void in her, and for a long time. I always thought she and my dad had come to California to better their lives. After that trip I started thinking she’d come to make things better for my brother and me. I wore the responsibility of that, like I wore the orange dirt stains in my sneakers.

hawker-fare-thailand-1

Photo by Eric WolfingerLess than two years later I traveled to Moms’s village again. It had changed in small, noticeable ways. The roads now were all paved, and Ubon was getting bigger, sprawling farther and farther out.

Shopping with Moms at the fresh markets in Ubon made me think all over again about how weird it must have been to leave this to move to California. Things spill into sidewalks here, there’s a density of people and food and vehicles, there’s color and flowers. Oakland must have seemed comparatively empty, people living life indoors. It must have been hard to stay positive, to not feel completely depressed as a refugee.

That must be the original driving force behind a lot of food in America: the need to adapt, to keep alive a shred of who you were before you left your home village, and raise your kids in a way that makes sense to you. Having us work at the restaurant was a way to teach us the value of hard work and being resourceful, but also to keep us under her eye, like we would have been if we’d grown up in her village. Mom- and- pop family restaurants in the States are ways for people like my parents to try and control their own destiny. It was trying to take charge of the disconnect, the rupture, between the old world and the new one.

I think that’s the universal experience of kids whose parents came from Asia: making sense of that rupture, that sense of disconnect and adaptation, and finding our own identity there. Not in its so- called purest sense, in Isan or Laos for me. It’s finding my place in the rupture of my family’s experience. It’s not about trying to reconcile two worlds that can’t easily merge, like fine dining and rustic food, Commis and Hawker Fare. It’s about keeping the rupture open.

From Hawker Fare by James Syhabout. Copyright 2018 James Syhabout. Excerpted with permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins.

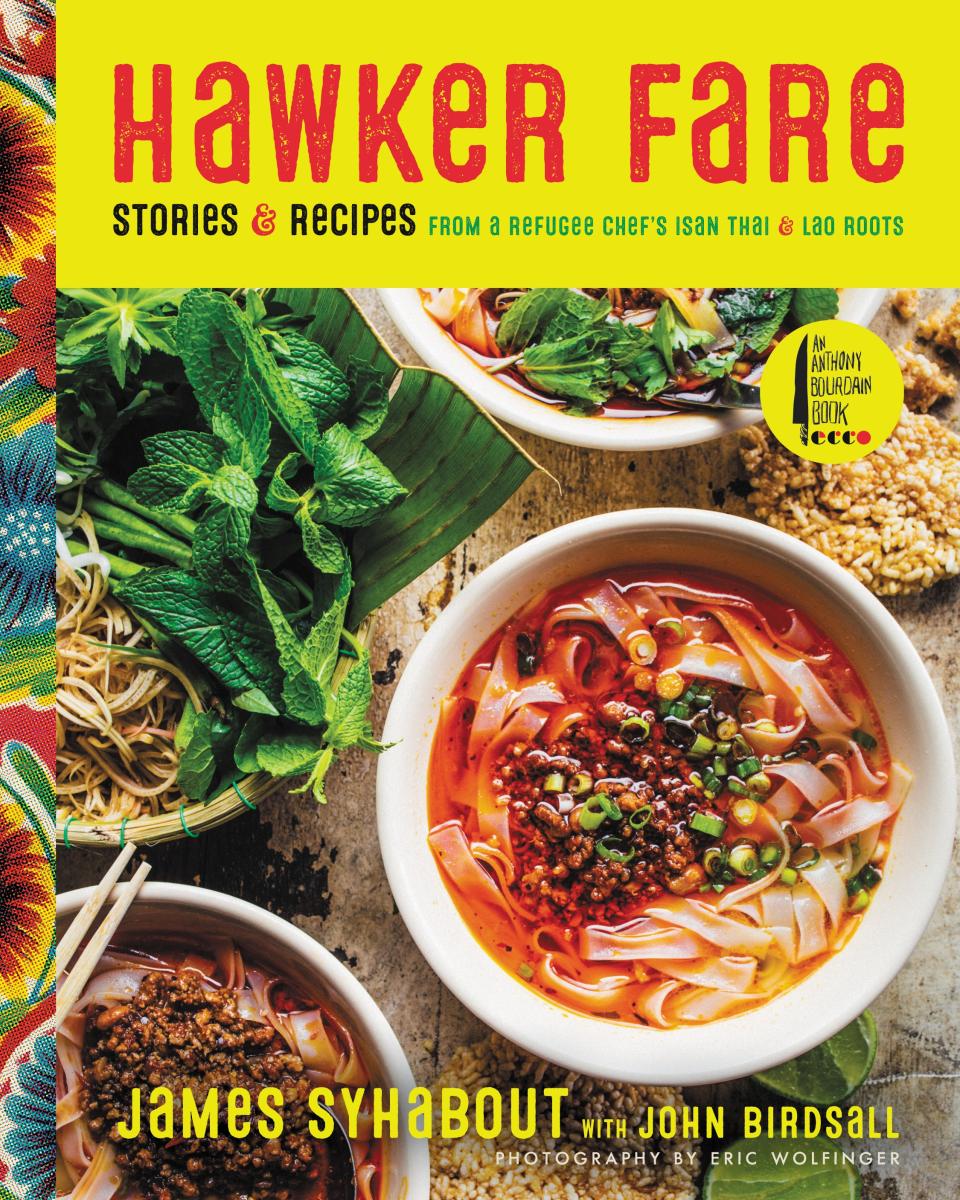

Buy it: Hawker Fare: Stories & Recipes from a Refugee Chef's Isan Thai & Lao Roots is on Amazon for $26.