How the federal government can save money by following a to-do list

Every two years a small federal agency publishes a comprehensive list of pain points in the federal government.

Based on a careful analysis, the Government Accountability Office creates a high-risk list of programs where at least $1 billion is at stake and the possibility of mismanagement or fraud exists. The list is a veritable manual for agencies and Congress to make necessary repairs to programs. It is available to anyone who wishes to read it.

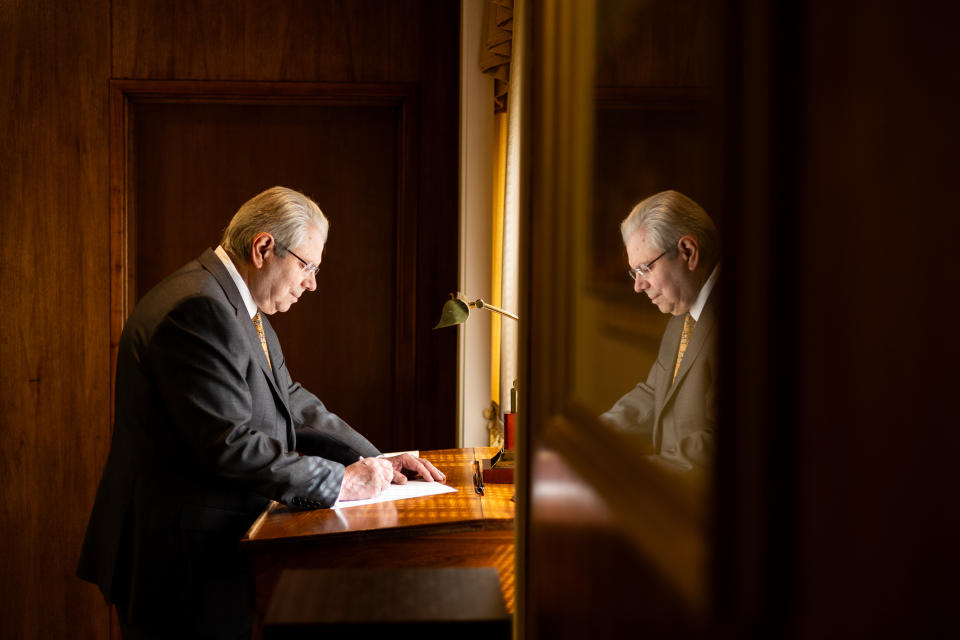

“In my 16 years in Congress, I would say that’s the single most important report we get on a regular basis,” said Rep. Gerald E. Connolly (D-Va.) “I think it is an absolutely necessary analysis of current issues and issues that are looming.”

“It can be a catalyst for action, certainly for Congress, but also for agency leaders as they’re trying to determine where to focus their energy. That in turn can be a tremendous value for the American public,” said Michelle Sager, GAO Managing Director for Strategic Issues, who oversees the high-risk program.

The latest list, released in early 2023, has 37 recommended action items with three added since 2021: management of public health emergencies, the potential for fraud and waste in unemployment insurance, and management of federal prisons. Other pressing issues include the need for programs to prevent and respond to illegal drug use, better oversight of food safety, management of financial risks related to environmental cleanup and climate change, and better cybersecurity overall.

The federal government would save an estimated $675 billion over two decades if the problems could be resolved, according to the GAO. This number could be even larger, the agency estimates, if specific fixes to certain agencies also happened, remedies that could improve service to the public and strengthen government performance and accountability.

- - -

How the High-Risk List began

The GAO started producing the list in 1990, in response to a request from two committee chairmen. Sen. John Glenn (D-Ohio) of the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee and Rep. John Conyers Jr. (D-Mich.) of the House Government Operations Committee had asked whether other agencies suffered from the same types of financial mismanagement that had been recently revealed at the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The GAO went a step farther, crafting a list of programs that its reviews, and the reviews of others, had found to be the most vulnerable to losses.

The result was a list of 17 items.

Today, the high-risk list draws from a regular stream of reports the GAO issues each year numbering in the hundreds, making more than 1,000 recommendations. Agencies typically act on 80 percent of the recommendations within five years, the GAO says, but more than 5,100 remain open - many of which are in turn cited in the high-risk report. The GAO also issues annual reports highlighting recommendations it considers to be the highest priority for each agency. Many problems are recognizable from daily news headlines, such as enforcing tax laws, providing quality health care for veterans, and risks of fraud and improper payments in programs such as Medicare and Medicaid.

Some, however, are perennial: the struggle to modernize information technology, especially cybersecurity, has been on the list since 2015. “Strategic human capital management” has been a high-risk item since 2001, referring to a persistent shortage of employees with skills in fields such as science, technology, engineering, mathematics, cybersecurity and acquisitions, and inadequate training of current employees.

“Those are probably some of the biggest cross-cutting themes because they are so critical to agency operations,” Sager said. “You can’t accomplish the mission without the people. And given the reality of how we all work in 2024, you have to have the technology in place to protect government information as well as to accomplish that mission electronically.”

Also common to many of the high-risk programs is the need to improve coordination on issues that include several federal agencies, such as emergency response and responding to climate change, or that involve both federal and state government agencies, such as unemployment insurance.

- - -

Agencies can fall off the list. Some never do.

GAO has officials with expertise in financial management, government operations, information technology, national security, tax policy and administration, and many more subjects. They meet regularly with agency officials, members of Congress and their staff, and the White House Office of Management and Budget on specific high-risk issues.

As an arm of Congress, the 3,500-employee GAO has the advantage of being independent from presidential administrations. That is also true for inspector general offices within agencies, another set of internal government watchdogs. There are more than 70 such offices, ranging from AmeriCorps to the U.S. Postal Service, that conduct their own audits and investigations.

The high-risk list is not the only overview assessment of government operations in need of attention.

The inspectors general produce annual reports on the most significant management challenges within their respective agencies, many of them raising the same issues as the GAO high-risk list, according to a report issued in March by the central council of IGs: 75 percent cite issues with information technology; more than 50 percent cite personnel issues; and nearly 40 percent cite issues with finances, procurement and grants.

Also, each presidential administration since George W. Bush has set a President’s Management Agenda of government-wide priorities. The Biden administration’s version (at performance.gov) focuses on hiring and developing federal employees with required skills; improving procurement and financial management; and improving federal agency services to the public. In addition to these initiatives, each agency has its own set of priority goals.

Success does happen. Sixteen of the 34 areas that had been on the 2021 list showed improvement, with only one declining - modernization of Defense Department business systems. GAO called that the best performance in the eight years since it started using its current standards for measuring progress.

To get off the list, agencies must show progress in five areas: leadership commitment, identification of the root causes, an action plan, regular internal monitoring, and a capacity to resolve the risks. The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp.’s insurance programs resolved its problems largely because Congress provided more funding. The 2020 Census came off the list because the Census Bureau addressed concerns about data quality and management.

Almost 40 percent of programs cited on the list over the years have been expunged because of the attention given them by the agencies, by Congress or both. To help agencies get their programs off the list, the GAO in 2022 issued a special report describing how that was done with four items: management of the Defense Department’s supply chain; gaps in weather satellite data; sharing of terrorism-related information; and the work agencies do under contract to each other.

Five of the programs from the original 1990 list are still on it: enforcement of tax laws, improper payments in the Medicare program, and purchasing by the Defense Department, the Energy Department and NASA.

That’s not to say that progress hasn’t been made; new issues arise even as old ones are addressed. For example, the main concern about tax law enforcement in 1990 related to collecting “accounts receivable.” The most recent report focused largely on fighting fraud arising from identity theft.

“We’ve closed literally hundreds of recommendations since the initial designation on the list. But there have also been some pretty fundamental transformations to the IRS and how it functions, Sager said. “Even though that area remains on the high-risk list the nature of it has changed over time and there has been tremendous progress on it as the issue has evolved.”

- - -

Technology is a perennial problem

Cybersecurity is another constantly evolving concern, as new technology leads to new threats. When it first appeared on the list in 1997, the focus was on Y2K - the potential for computer breakdowns due to coding issues when 1999 turned to 2000. Now, the focus is on protecting personal information and guarding critical IT systems against cyberattacks.

Cybersecurity is an example of an area where risk never will be eliminated, explained Chris Mihm, who ran the high-risk program at GAO from 2000-2021 and is now an adjunct professor at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University.

“The issue is if it’s being effectively managed by the agency, by the government,” he said. “In that case, you can envision some of these being taken off the list. The idea is that they should be able to come off through effective management of the risk.”

Fixes are not always entirely within an agency’s control either. Of the 37 items on the current list, GAO indicates that changes in law are “likely to be necessary to effectively address” 11 of them.

Connolly, whose Northern Virginia district is heavy with both federal workers and tech companies, has made the list a centerpiece of his work in Congress on information technology and federal employment issues. He helped to enact a law setting standards for improving information technology in areas such as cybersecurity in the federal government and a separate law that created a central fund for agencies to replace obsolete technology rather than continue the expense of maintaining it year after year. The challenge, he said, is to convince legislators to delve deeply into how the government functions and to remain focused on it.

Congress “is hit and miss on this,” he said, citing his experience with creating the technology fund. After years of regular appropriations, plus a $1 billion infusion from a pandemic relief law, the federal budget enacted in March that funds federal agencies through September does not provide more funding and actually revokes $100 million previously allotted but not yet used.

“That’s taking a huge step backward,” Connolly said.

Release of each biennial list - the next is scheduled for early 2025 - traditionally triggers renewed attention on Capitol Hill, as the oversight committees of both the House and Senate hold hearings.

“They kind of serve as kind of an oversight agenda-setting mechanism for those committees as they begin each Congress, as they’re looking across government and thinking about what they want to focus on for their oversight agendas,” Sager said. “Oftentimes these are the same types of issues they’re hearing about from their constituents.”

The report also will land in the hands of many new top leaders in federal agencies, regardless of the outcome of the presidential election. A new administration brings in its own set of political appointees, but there also is substantial turnover among those top officials at the start of a second term for a president who is reelected.

“They can turn to the high-risk list and the related open recommendations to provide them with a way to really dive in and have those facts in hand that they can focus on,” Sager said. “This provides them with somewhat of a road map, if they’re trying to focus their attention on targets of opportunity to show progress and make a difference.”

- - -

Eric Yoder was a reporter on The Washington Post national staff for more than 20 years, focusing on federal employee issues, the budget and government management issues.

Related Content

Fentanyl is fueling a record number of youth drug deaths

In a place with a history of hate, an unlikely fight against GOP extremism

Life in Taiwan is rowdy and proud, never mind China’s threats