How exactly will Panther Island’s new bypass channel prevent flooding in Fort Worth?

Editor’s note: A version of this story originally published on March 4, 2019.

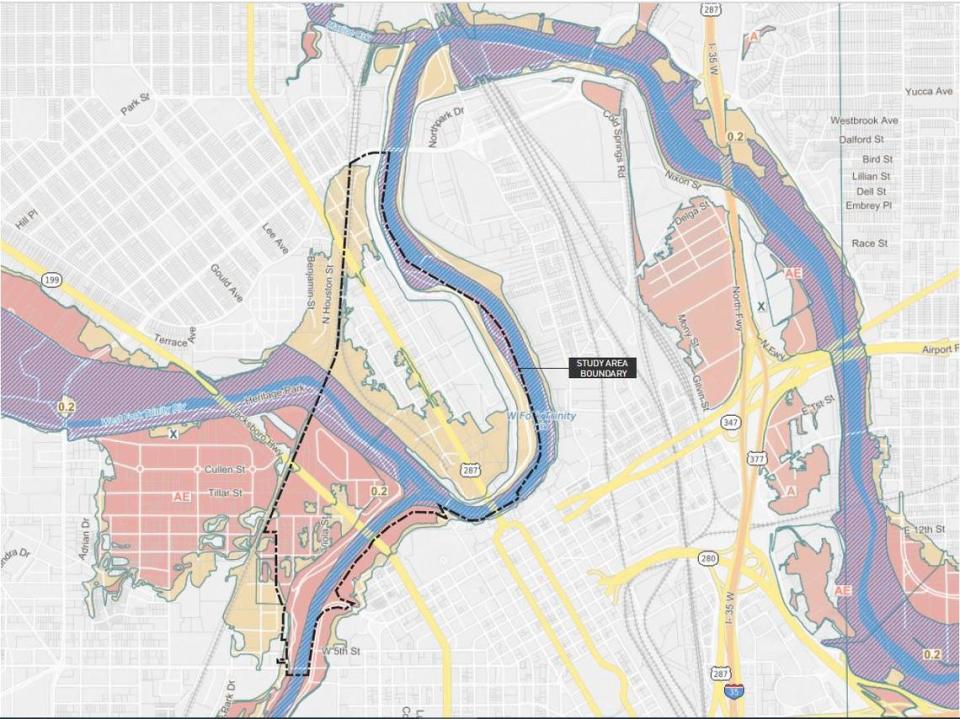

The new bypass channel for the Trinity River near downtown Fort Worth will do more than create the actual islands for the multibillion-dollar Panther Island redevelopment.

The bypass channel is a key part of a major federal project that aims to reduce the risk of flooding. It’s called the Central City Flood Control Project, and the U.S. Corps of Engineers is in charge of it. Once the Corps builds the 1.5-mile bypass channel, some existing earthen levees near downtown can come down, which will open up land for mixed-use redevelopment — aka Panther Island.

But for some, questions have lingered for years: Is Panther Island a legitimate flood control project? Or an economic development plan masquerading as flood control to tap federal money? And how exactly does this big dig prevent flooding?

In the Spotlight: Panther Island. Star-Telegram journalists answer your questions about the future Fort Worth development. Read more. Got a question? Use the form at the bottom of this story.

Backers of the endeavor have said for years that the flood control project is necessary to pull thousands of acres of prime real estate out of a flood plain. Opponents have said it’s simply a gleaming opportunity to re-imagine downtown Fort Worth that ignores real flooding issues.

Woody Frossard, an engineer with Tarrant Regional Water District, has been involved with the Central City project since 2003 and served as project manager. He told the Star-Telegram in 2019 that the project does address flooding risks for multiple neighborhoods.

”It’s not some flood somebody dreamed up sitting back somewhere,” he said. “These really do occur and they’ve occurred in Texas.”

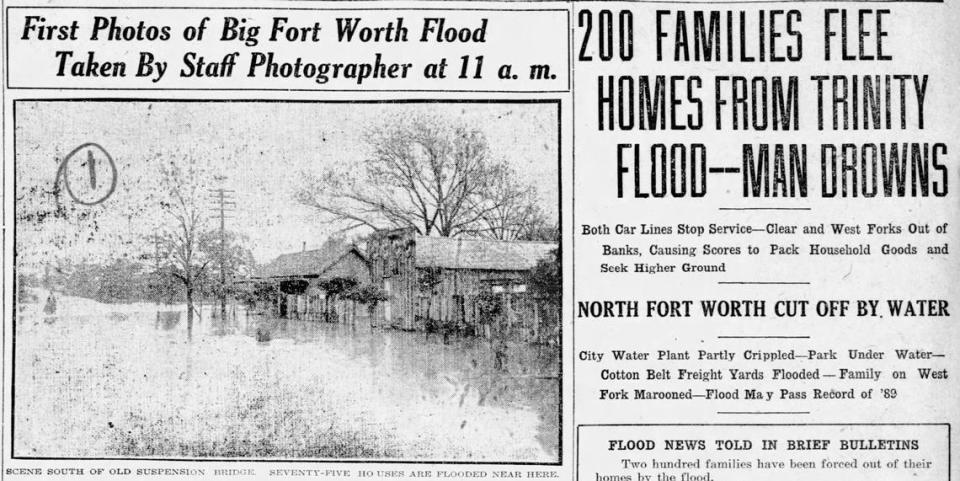

Devastating floods have inundated Fort Worth multiple times. On July 5, 1889, the Fort Worth Gazette reported “that thousands of people visited the bluff to see the huge sheet of water surrounding Fort Worth beyond the river.”

Disaster hit again in 1908.

In April 1922, torrential downpours dumped 11 inches of water in two days; Trinity River levees had 17 breaches that led to 10 deaths.

In 1938, Marine Creek flooded the Stockyards and much of the north side.

But the most notorious Fort Worth flood was in May 1949, swallowing much of the city’s west and central districts after 10 inches of rain. Ten people died and 13,000 lost homes. Today’s West 7th district, the Fort Worth Zoo and Colonial Country Club were knee- to shoulder-deep in floodwaters.

The 1949 flood led to beefed-up levees on Clear Fork and West Fork through downtown Fort Worth.

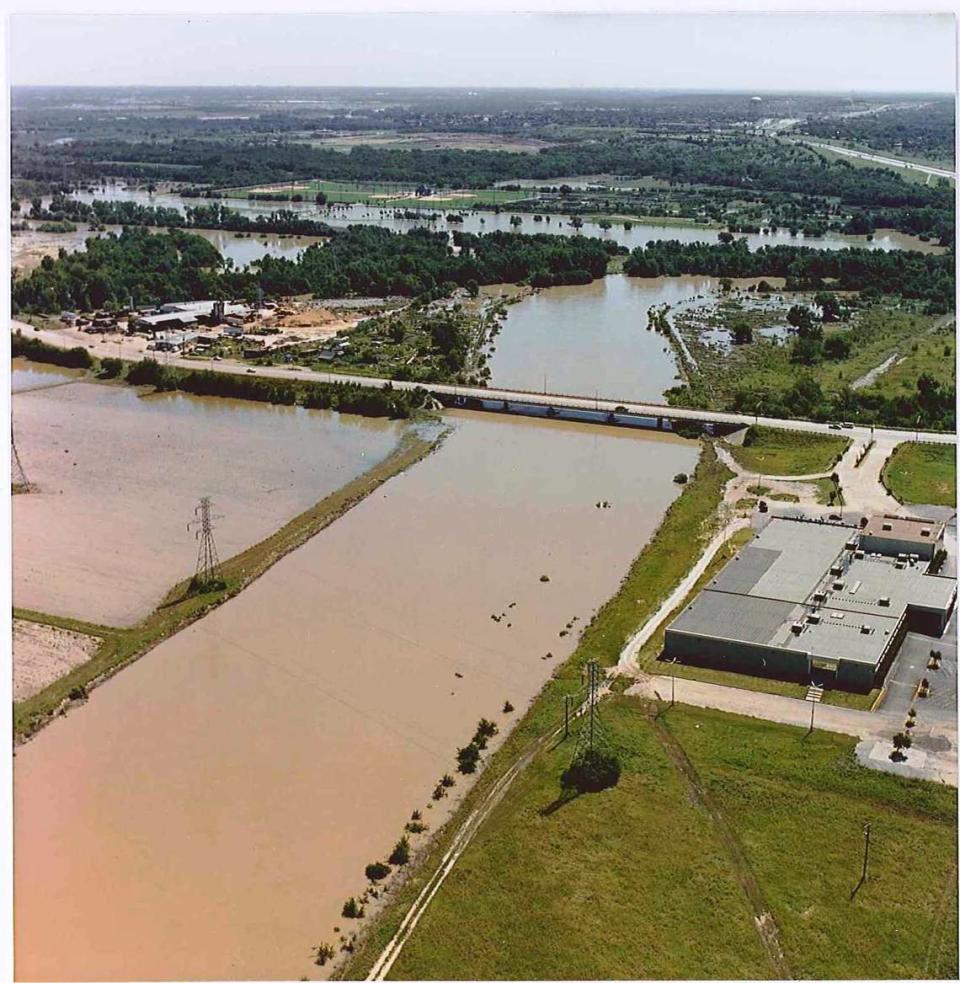

Since then, some of the worst floods were in 1989, 1990 and 1991.

How will Trinity River’s new bypass channel prevent floods?

So why is Panther Island needed and how exactly does the bypass channel mitigate flooding?

Fort Worth’s 21 miles of levees along the river can no longer protect the city adequately from a major flooding event, Frossard said. That’s largely because of the boom in development since the levees were built in the 1960s. More pavement means the ground is less able to absorb rain before it runs into the river.

The project won’t alleviate the urban flash flooding that has increasingly plagued Fort Worth streets. And it doesn’t protect an area that regularly sees major flooding.

Instead, it pulls about 2,400 acres out of the flood plain for what the Army Corps of Engineers calls a “standard project flood,” the most severe flood considered possible for a region. Property value was estimated to be worth more than $2 billion in that area but updated numbers weren’t available.

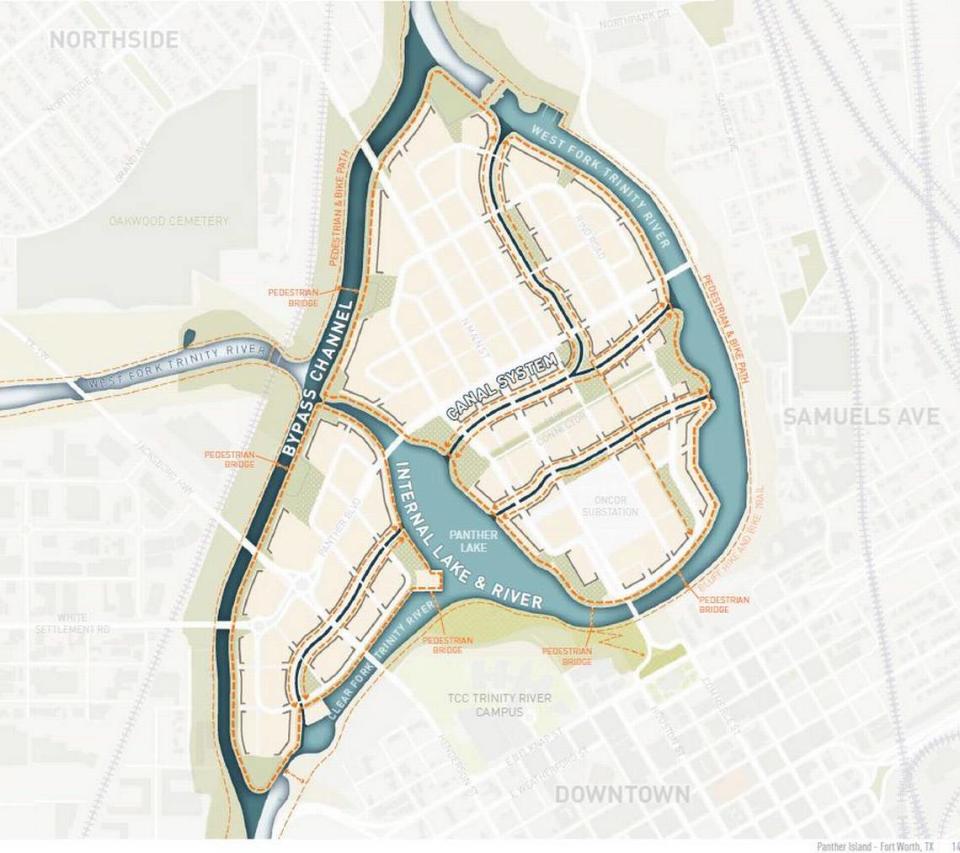

That area includes the future Panther Island, a former industrial zone that would transform into about 800 acres ripe for development.

Engineers believe the project would protect several neighborhoods along both forks of the Trinity River, including parts of Linwood, Crestwood, the West Seventh Street district and the area west of Brookside Drive around Isbell Road. Burton Hill and River Oaks would also be protected.

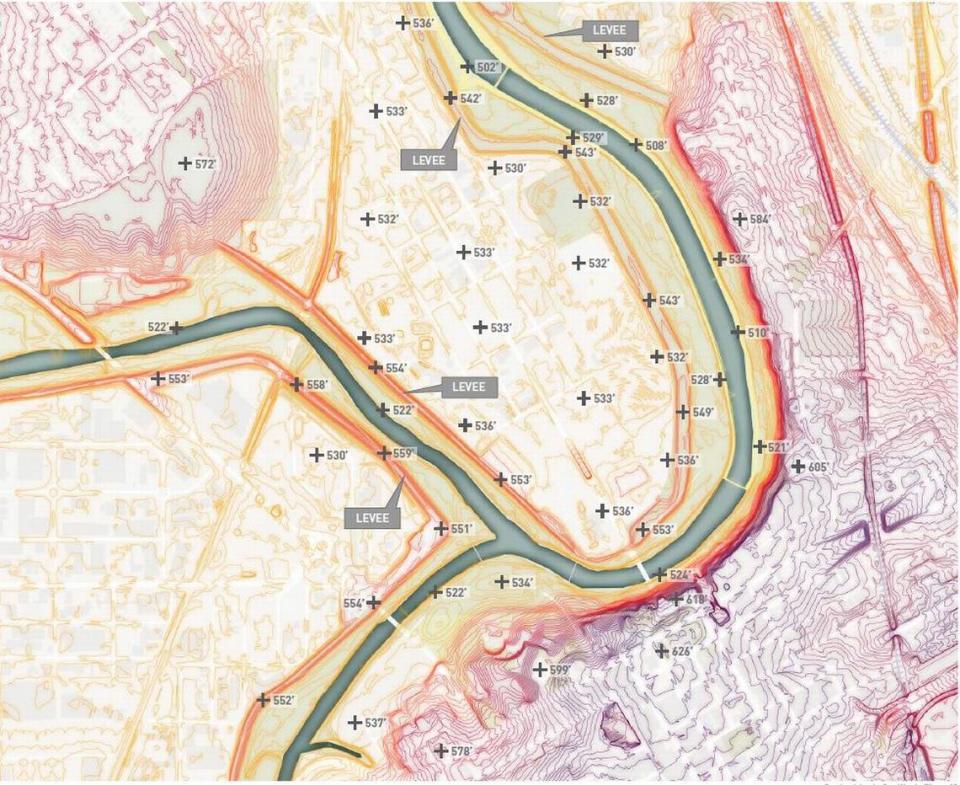

The Clear Fork and West Fork meet just north of downtown, where they immediately flow against the bedrock bluff the city is built on. The larger river then flows around a tight U-bend before heading downstream.

In heavy rain, that confluence slows the flow of water, increasing the risk for flooding upstream, said Frossard, of the Tarrant Regional Water District.

The new bypass channel essentially skips the U-bend, allowing the water to flow quickly downstream during a flood stage.

This means more water moving faster toward downstream cities such as Dallas. To prevent that, overflow basins are being constructed in Gateway and Riverside Park. During a flood, water will top the levees along the parks, spilling water into the basins and slowing the flow.

The proposed canals and small lake within the new islands would serve as a secondary flood-control measure, capturing stormwater runoff.

Why not raise the levees instead of building a new channel?

Some have argued that the cost has ballooned too much and the city would have saved time and money had it gone with an overhaul of the levee system.

When looking at any project, the Army Corps is required to examine alternatives.

The alternative explored for the Trinity River was to raise two of the 12 levees in the city at a cost of about $10 million.

Frossard said that plan was a no-go from the beginning. Raising only two levees kept the rest of the city vulnerable, and raising all the levees would have been too costly. The Corps never priced raising all 12 levees, he said.

Read more:

→ What is Panther Island? Facts to know.

→ Why is it called "Panther Island"? Here's the history

→ Will anyone be able to afford to live on Panther Island?

🚨Get free alerts when news breaks.

To be structurally sound, levees require three feet of base width on each side for every foot in height. In heavily-developed Fort Worth, raising the height of the levees would require obtaining more private property, largely from homeowners, than the Panther Island bypass. Fort Worth has about 21 miles of levees along the Trinity.

Raising the levees also requires moving utilities and raising several bridges. Under one part of a the levee plan, a watertight gate would need to be closed manually on either side of the river, Frossard said.

“I don’t know why we, as a governmental entity charged with protecting Fort Worth, would choose to only protect part of Fort Worth,” Frossard said of the Corps’ alternative of raising only two levees.

Levee size is an issue in urban areas, said Dave Dzombak, a water infrastructure expert and head of Carnegie Mellon University’s civil and environmental engineering department.

To be effective, all levees in the system must be brought to the same height. Dzombak pointed to New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina, where a mishmash of levees built at different heights and to different standards exacerbated flooding.

When not all the levees in cities can be raised at once, cities struggle to decide which land should be protected first.

“It becomes a battle of levee height,” he said. “Who’s building the tallest levee to protect what neighborhood?”

Local advocates have long said Panther Island not only avoids raising the levees, but it also provides a unique development rivaling San Antonio’s River Walk. The channel creates miles of new riverfront property in central Fort Worth.

To make that happen, significant work is needed on the future island, including new roads, sewage and storm water lines. All of that must be funded with local dollars.

A special 40-year tax district was established to help fund development, but most of the district’s projected revenue would be generated from development that would occur on the island. In 2018, voters passed a $250 million bond, which will pay for infrastructure on the island including some flood control.

This story contains information from the Star-Telegram’s archives.