Environmental group has major concerns about Eastman Chemical’s plastic recycling process

Note: Eastman Chemical Company’s first “molecular recycling” facility is now fully operational in Kingsport. It uses a process called methanolysis to reduce hard-to-recycle waste plastic to its original molecular state for reuse in plastic production. Eastman expects the main end product, recycled “DMT,” to capture large market share in durable plastic and packaging sectors because it removes plastic from the waste stream and makes progress toward a “sustainable economy.” News Channel 11 got an exclusive first look around the facility and brings you this and several related stories.

KINGSPORT, Tenn. (WJHL) — While Eastman Chemical’s molecular recycling technology may have won company leaders the ears of regulators and the favor of brands wanting to woo eco-conscious consumers, not everyone is convinced the benefits are so clear.

“They’re trying to come up with something that seems like a solution but isn’t,” National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) Director of Plastics and Petrochemical Advocacy Renee Sharp told News Channel 11 in a Zoom interview. Sharp called chemical recycling as a whole a largely unproven technology, at least at large-scale, that has significant negative environmental impact.

News Channel 11 reviewed several hundred pages of documents produced for the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC) since Eastman began the permitting process in late 2020 for construction and then operation of the methanolysis plant.

Eastman execs see lucrative future for molecular recycling

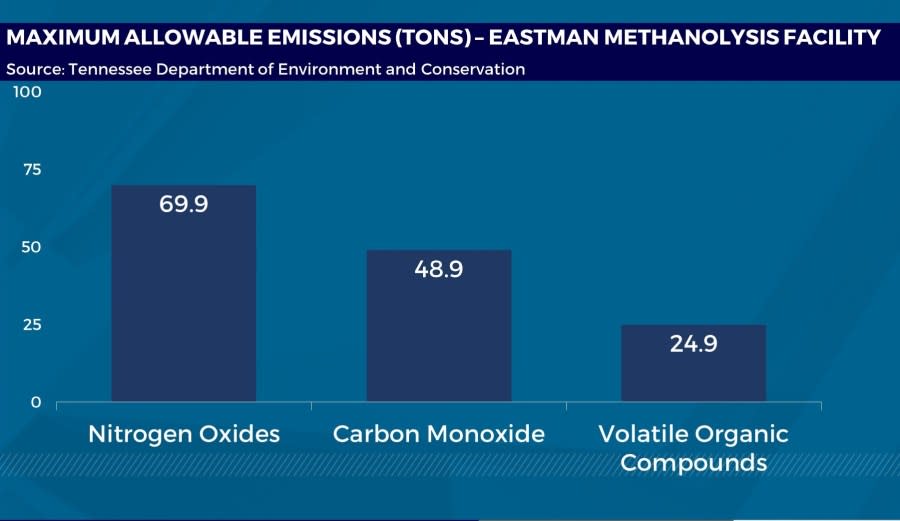

Eastman has modified the permit twice to account for changes in pollution control equipment. TDEC’s most recent permit was issued Nov. 1, 2023 and expires Oct. 31, 2025. It allows the facility to emit more than 150 tons a year combined of air pollutants like carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides and EPA-designated hazardous air pollutants, including volatile organic compounds like methanol (4.7 tons per year) and acetaldehyde (2.2 tons per year).

“We basically know that these processes create hazardous waste, they create hazardous air pollution and they can also be used to create fuels, which can also have a lot of toxic implications,” Sharp said.

Eastman’s latest annual report seems to partially acknowledge the uncertainty Sharp mentioned. Full of references to its “sustainable innovation initiatives,” it offers this caveat to investors in the “Risk Factors” section of its 10-K filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission:

“There can be no assurance that such innovation, development and commercialization or licensing efforts … will receive necessary government or regulatory approvals, or result in financially successful commercialization of products, or acceptance by existing or new customers.”

Eastman Chief Technology Officer Chris Killian, though, thinks the regulatory environment is tilting in Eastman’s favor even though molecular recycling, at least at scale, is in its early days.

“Our view of the current regulatory landscape is that the regulations that we see coming out of Europe, coming in various states in the U.S. are actually favoring technologies that are repurposing of waste plastic for the conversion of that plastic back into raw materials,” Killian said. “You’ve got a regulatory environment in Europe for example where ever-increasing levels of recycled content are required of our customers, of the brands in the market.”

That said, Eastman is making its play at a time when research into the risks of microplastics and calls for strict reductions in plastic use are at all-time highs. Sharp said she believes companies like Eastman are responding to “a clear recognition that there is a plastic crisis” with sustainability or “circular economy” segments of their portfolios to “appear like they are solving the problem.”

“What we really need is, we need less plastic, we need redesign and we need reuse, but the plastic and chemical industries … they of course want to keep making more chemicals and making more plastics,” she said.

NRDC weighs in after $375M grant announcement

The NRDC indirectly referenced Eastman after the Department of Energy announced the company would receive up to $375 million to offset costs for a molecular recycling operation at its Longview, Texas plant. The money is available because the facility plans to incorporate low-carbon processes like battery storage and solar.

Eastman reckons recycled DMT production will benefit area recycling programs

NRDC’s policy director for industry, climate and energy, Christina Theodiridi, singled out petrochemical projects in a blog post about the 33 projects that will get up to $6 billion in federal money for “clean energy demonstrations.”

She said some awards in the steel, cement and aluminum industries could help “decarbonize” those sectors through technology innovations, saying for instance that the six cement and concrete projects “hold a lot of promise to deeply decarbonize the sector.” Among her “lowlights” was concern “about the profound harms to people and the environment caused by the petrochemicals and plastics sector, including from facilities greenwashed as so-called ‘chemical recycling.'”

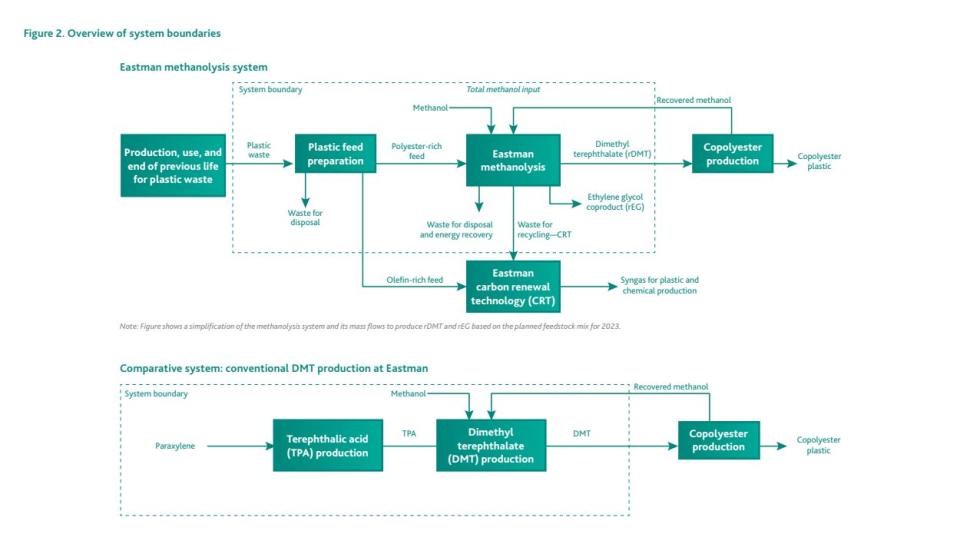

The NRDC referred News Channel 11 to Sharp, who reviewed an Eastman-commissioned “life cycle assessment” to compare the global warming potential “and other environmental indicators” of its methanolysis recycling with its traditional paraxylene-derived DMT production.

Published in early January 2022, the study uses “process design data” for r-DMT production since the company wasn’t producing it yet. It found 29% lower greenhouse gas impact, and better results in 13 of 14 overall categories related to the environment and human health.

Sharp questioned the study’s findings. She noted that the molecular recycling showed several byproducts that aren’t part of the standard DMT production at Eastman. They include waste for disposal and energy recovery, as well as “waste for recycling” going to a second process, carbon renewal technology. Output from that “CRT” is shown as “syngas” or synthetic gas “for plastic and chemical production.”

Sharp said the NRDC considers the various processes that producers deem “chemical recycling” tend to be “very toxic, they’re often very energy intensive (and) they create a lot of hazardous waste.

“I would say all of them are also very, financially and kind of process-wise, very unproven. But they really need to appear like they’re doing something and so this is their plan.”

But Killian said what Sharp refers to as waste (as does the life cycle assessment) “are actually co-products from the process.”

He said Eastman can “upgrade that material through a recycling process into high-value goods that we can give a new life to in the marketplace.”

He said pyrolysis, another type of chemical recycling, has around 60% “material to material” — meaning close to half the inputs are not recovered — while methanolysis is 90% material to material.

‘Chunk,’ ‘nerds’ and densifiers — Eastman’s molecular recycling explained

“When you talk about … advanced recycling there’s a lot of confusion and education that we need to do as a company around the differences between those technologies,” Killian said.

A three-decade veteran of bringing innovative technologies to the marketplace, Killian said “anytime you bring new to the world technology to market there’s always questions, skepticism around the technology.”

Sharp said that’s with good reason in this case, particularly with the coproducts that are part of the methanolysis.

“Eastman carbon renewal technology, syngas for plastic and chemical production, that basically means they’re creating fuels that are going to be burned,” Sharp said.

“We know some fuels have been approved, semi-approved for creation from plastic waste that we know to have incredibly hazardous chemicals in them. And when I say incredibly hazardous, I mean like the EPA’s own calculated cancer risk was like one in four people exposed to this chemical over a lifetime get cancer.”

Sharp said the specifics of Eastman’s process remain largely unknown. Indeed, as it worked through the process with TDEC, some of the emissions totals shifted.

For instance, requested “maximum allowable emissions” for nitrogen oxides emissions were 44 tons annually in a December 2020 application, very early in the process, but were 69 tons in the most recent application from late October 2023. Volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions projections also increased, from 17.2 tons per year in late 2020 to nearly 25 tons in the most recent application.

Conversely, carbon monoxide estimates fell from 55 tons early in the process to just under 49 tons.

Eastman has existing processes that produce greater amounts of certain pollutants. Its current permit for producing organic chemicals/acetic anhydride, for instance, allows up to 370 tons of VOC emissions each year and up to 170 tons of nitrogen oxides.

Another permit, for production of cellulosic esters, permits 4.6 tons of acetaldehyde annually — double the allowance for the methanolysis permit — and 4 tons of another hazardous air pollutant VOC, propionaldehyde, that isn’t emitted in the chemical recycling process.

Sharp said she doesn’t buy the insistence that continued plastic production is a viable solution to the world’s increasingly obvious problem with plastics and their impacts on health and the environment.

“I want to give them credit for trying, except they’re trying in the wrong way,” Sharp said. She said the innovation needed is “creating a new economy where we’re moving towards more nontoxic materials, nontoxic chemicals and nontoxic processes.

“Instead they’re just doubling down on … their current scheme and then essentially sinking a lot of money into processes perpetuate or just kind of make new problems.”

Scott Ballard, president of Eastman’s plastics division, said unlike previous technology that requires tradeoffs to be environmentally friendly, “we’re trying to innovate so that there is no sacrifice — so that the best thing for the world is the best thing.”

Ballard pushed back against the naysaying.

“It’s somewhat discouraging sometimes when you have people in different agendas trying to take shots at what you do when you know the purity that’s in your heart and your objectives. But that’s part of leading change.”

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media, Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to WJHL | Tri-Cities News & Weather.