It's the end of the world as we know it, and investors feel bullish

Around the world, in nations large and small, developed and emerging, there has been a retrenchment of democracy and an emergence of previously fringe political elements to the mainstream. That has been accompanied by significant government dysfunction.

In the United States, President Donald Trump, with the lowest-ever approval rating for a president in his first year, has presided over one of the least productive Congress (measured by laws enacted) in at least 40 years.

And in Europe, Italy was unable to form a government for three months; Germany took nearly six months to put a government in place; Paris is at a standstill as medical workers, trash collectors and pilots join striking train workers to oppose French President Emmanuel Macron’s attempts to institute labor reforms.

China has made Xi Jinping president for life; Nicolás Maduro has dissolved Venezuela’s parliament and taken the presidency hostage; Vladimir Putin has been elected president a fourth time in Russia, as an ever-growing list of opposition figures end up dead or exiled before challenging him; Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan thwarted a coup attempt in 2016 and has cracked down on dissent and free elections; South Africa recently deposed its scandal-plagued president; Brazil impeached its president in 2016, and the president who preceded her is now in jail, as a retired Army captain who has spoken favorably of the country’s previous military dictatorship leads the polls; Malaysia just elected a former dictator as its prime minister, following in the footsteps of Nigeria, which made its former dictator president two years before.

This is all part of a trend. U.S.-based democracy advocacy organization Freedom House reported earlier this year that 2017 was the 12th consecutive year of a decline in global freedom.

“Since 2008 the world has entered a period of economic dysfunction,” George Friedman, author of “The Next Decade” and “The New American Century,” told Yahoo Finance. “There is a tendency of moving away from the pure liberal democratic model that’s really been driven by the failure of that model economically and socially.”

‘There’s not … a premium to having democracy’

That economic dysfunction is the result of governments responding to the global financial crisis of 2008 by saving the banking system without providing a lifeline to working-class citizens, says Friedman, an international affairs strategist and founder of Geopolitical Futures.

China’s rapid ascent and its growing debt bubble along with the rise of globalization have created significant new wealth, but the lion’s share has been amassed amongst the top earners, no matter their geographic location.

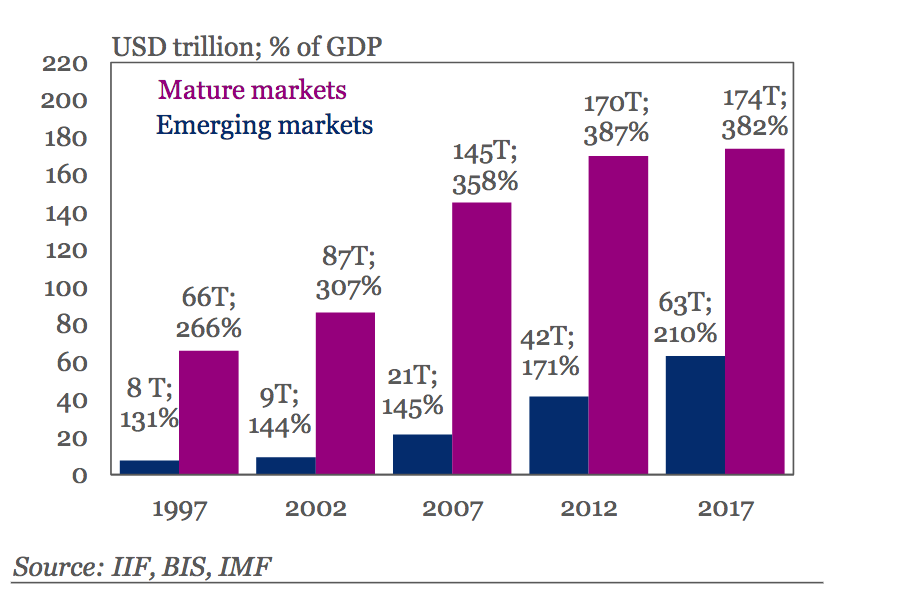

Curiously, the growth of unconventional and undemocratic regimes has occurred in concert with ever greater investor allocation to financial instruments. Debt has risen to a record $237 trillion, as more companies and countries issue bonds, and equity investment remains near all-time high levels. Allocation to stocks and other risky financial assets rose to all-time highs earlier this year, data from Jefferies shows.

“There’s not historical evidence that there’s a premium to having democracy,” said Vincent Reinhart, chief economist at Standish Mellon, part of BNY Mellon Asset Management North America.

Reinhart, like many asset managers and economists, cites both the U.S. and global trends of falling unemployment, accommodative monetary and fiscal policy and increasing gross domestic product as reasons to favor riskier assets like stocks over safe-haven assets like U.S. government bonds.

The finance pros are bullish

A recent Reuters survey of more than 300 equity strategists and fund managers found they expect all 17 of the major indexes from around the world to rise from their current levels and close the year with gains. That’s despite 11 of those indexes posting negative returns so far this year and many being well below where they were predicted to be by mid- year in Reuters’ February poll.

Nearly 60% were confident or very confident world stocks will rise over the next 12 months. They were even more bullish in the February survey.

In years past, money managers avoided the prospect of governments that were dysfunctional or hostile to democracy. However, that thesis has been turned on its head as the number of countries with highly functioning governments dwindle and countries that emerge from crisis produce double- or triple-digit returns, no matter what government takes charge.

A great example of this phenomenon is Egypt, which has been described my numerous multinational and non-governmental organizations as a dictatorship but is expected to see its highest level of cash inflows from investors on record this year.

Even Venezuela has lured continued investment from Wall Street firms hungry for its high bond coupons, despite many in the country literally starving to death thanks to the so-called diet of rationed imports and medicine imposed by Maduro’s administration.

Consequently, much of the thinking about what makes a good place to invest has changed.

“There’s this notion that we saw more liberal democracies and more market economies and that those two went hand-in-hand,” Kate Warne, principal and investment strategist at asset manager Edward Jones, told Yahoo Finance. “I’m not sure that was true.”

An ‘improving trend’ in the emerging markets

Even flows to emerging markets, such as Brazil, South Africa, Malaysia and China, have taken off in recent years. Investors say that while the countries present more risk than developed markets like the United States, they now have deeper capital markets and stronger structural banking systems, despite their broad drift away from democracy.

“We are seeing a bit more autocratic behavior in several of the countries that we’re investing in,” said Peter Gillespie, a portfolio manager and analyst on the developing markets equity team at Lazard Asset Management. “What we’re seeing is more intervention in the companies that we’re investing in, so our companies are being asked to do more government service, some more national service. I would say at the moment it’s been fairly modest, but it certainly has the potential to be a bigger issue.”

Data from the Institute of International Finance shows that investment levels, which shifted toward developed markets in the years following the 2013 U.S. taper tantrum, had been shifting strongly back towards emerging markets since 2015. That trend has reversed since the appreciation of the dollar in April, but EM investors remain bullish on the asset class.

Lazard’s emerging markets team sees EM as currently in an “improving trend.”

“We’ve been very negatively skewed on geopolitical risks for the last two years, frankly,” said Lazard multi-asset portfolio manager Rupert Hope. “But at the moment, the economics and the synchronized nature of this particular growth cycle and what that meant for the growth of trade volumes in particular for emerging markets has really overwhelmed these issues.”

Dealing with unstable, corrupt and/or repressive regimes has simply become the norm for investors in emerging markets of late, said Ed Al-Hussainy, senior interest rates and currency analyst at Columbia Threadneedle.

“If you’re going to be an investor in emerging markets, you need to have a stomach for weak institutions,” Al-Hussainy told Yahoo Finance in April. “I cannot name a single major emerging market where institutional quality, particularly when it comes to democratic institutions, has improved in the last five years.”

Investors unfazed by Italeave

That appears to be true of developed or mature markets as well. Investors have maintained a largely rosy outlook on risk after last week’s turmoil in Italy sent markets around the globe tumbling. Italy’s new leadership looks poised to rethink the country’s participation in the European Union and the euro. That could deal another blow to the euro zone, the world’s third-largest economy, following 2016’s Brexit vote.

Jefferies data shows that U.S. and Asian equities saw inflows last week, and apart from Italian stocks, which have seen 12 straight weeks of outflows, bourses around the globe have seen money continue to flow to stocks.

“In bouts of uncertainty, it’s probably not such a bad idea to take on a little risk,” said BNY Mellon’s Reinhart. In fact, he added, given the global economy’s current strong fundamental environment, “It’s probably a good time for risk taking.”

—

Dion Rabouin is a markets reporter for Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter: @DionRabouin.

Follow Yahoo Finance on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn.