Vogue ’s Hamish Bowles Remembers the French Couturier Hubert de Givenchy

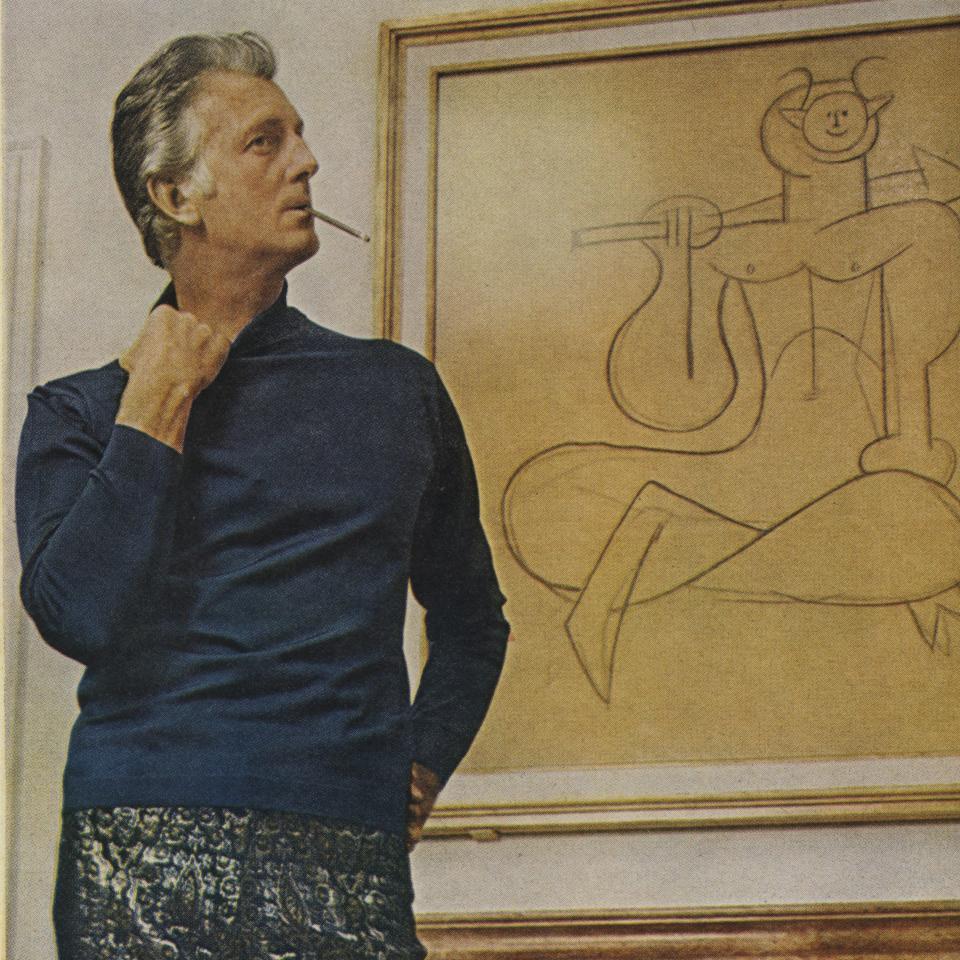

A stately 6-foot-5, with patrician good looks and piercing, forget-me-not blue eyes, the haute couturier Hubert de Givenchy, who has died at the age of 91, was a figure of great personal elegance, one whose restrained, intimidatingly well behaved clothes defined the way a generation of women aspired to look and dress, and whose taste in all things set the benchmark for impeccable French chic.

Givenchy’s father, the aristocrat Lucien Taffin de Givenchy, the marquis of Givenchy, died when he was 2, and Hubert was subsequently raised by his mother and his maternal grandparents. His grandfather, Jules Badin, was the director of the storied Beauvais and Gobelins tapestry workshops and instilled in his grandson a passion for textile arts that would later find expression in the fashion world. As a fashion-struck young man Givenchy initially attempted to work for the legendary Cristóbal Balenciaga, but the couture establishment’s directrice, Mademoiselle Renée, the terrifying Mother Superior defender of the gate, refused to let the two meet. Givenchy defaulted to Jacques Fath, who had emerged during the shadowy occupation dressing actresses and collaborationists, and who was famed for his personal charm, good looks, and the exaggerated glamour of his clothes, which appealed to va-va-voom clients from Rita Hayworth (who wore Fath to marry Aly Khan) to Evita Perón.

For Givenchy, the house of Fath “was a haven of fun and fantasy . . . like stepping into a universe of danger and sensuality.” From there, Givenchy left to work with Robert Piguet, a fellow Protestant whose clothes were notably understated and chic, and Lucien Lelong, a ringmaster stylist whose previous protégés included Pierre Balmain and Christian Dior. Following those appointments, Givenchy joined Schiaparelli, where he stayed for four years designing playful clothes for her boutique. After World War II, Elsa Schiaparelli’s light had begun to dim, but her boutique was a place of lively experimentation, and Givenchy met clients there who would remain faithful to him after he left to begin his own fashion house.

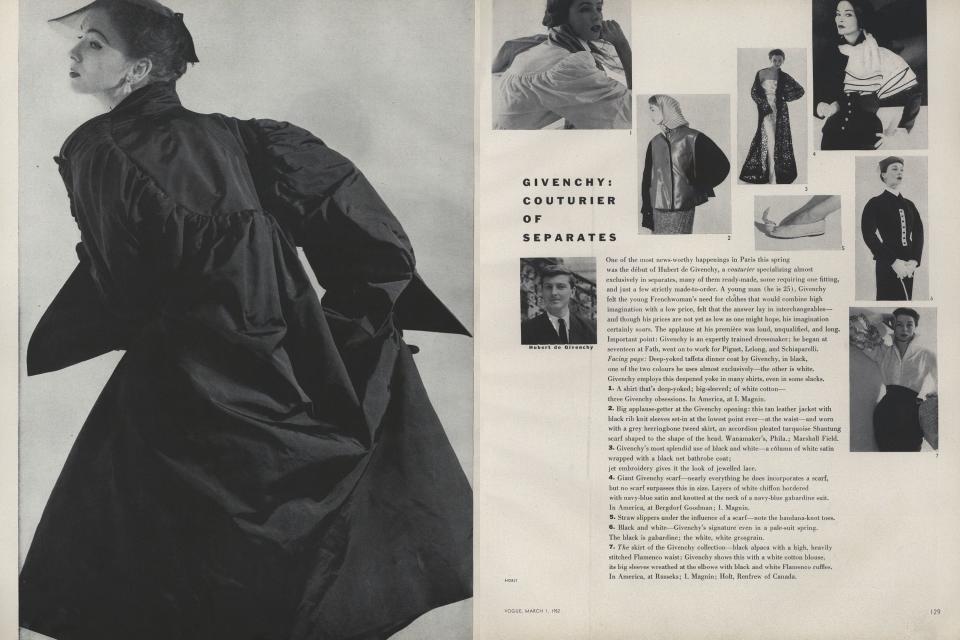

Chez Fath, Givenchy had befriended the designer’s star mannequin, Bettina Graziani, and when he left to establish his namesake couture house on Rue Alfred-de-Vigny in the genteel residential district of the Parc Monceau, she followed him there. The piquant Madame Hélène Bouilloux-Lafont served as directrice, helping to raise the necessary funds, and Graziani joined the small team, acting as muse, mannequin, and vendeuse of his house when the establishment opened on February 2, 1952. Vogue’s late Paris Bureau Chief, Susan Train, remembered the liveliness of those early presentations, with their innovative use of humble fabrics like cottons, witty trompe l’oeil prints of fur, embroideries of fruits and vegetables, and above all the prophetic focus on separates (“to make getting dressed an easier choice,” as Givenchy put it), including the wildly successful “Bettina blouse” of eyelet cotton with ruffled sleeves like the shirt of a maracas player, worn with a fitted linen skirt or capri pants. Fueled by his experiments at Schiaparelli, the designer envisaged a “luxury ready-to-wear,” and the house was an instant success.

However, Givenchy’s style was to undergo a sea change when in 1953 he was finally introduced to his idol, Balenciaga, by the fashion plate socialite Patricia Lopez-Willshaw at the house of Condé Nast’s urbane president, Iva S. V. Patcevitch. Balenciaga took the glamorous young man under his wing and nurtured him in his own exacting science of dressmaking, so different from everything that Givenchy had learned up to that point. “He was the complete creator,” said Givenchy of his paternalistic mentor, and there was soon a complete synergy between their collections, unparalleled in 20th-century fashion history, with a very similar use of silhouette, fabric, and embellishment, even if Balenciaga’s collections, like his clients, were generally a little statelier and Givenchy’s clothes more youthful, blending Balenciaga’s austere Spanish aesthetic with his own lighthearted French tastes.

Givenchy was soon dressing and befriending the gratin of society, from the duchess of Windsor and Marella Agnelli to the duchess of Devonshire and the young senator’s wife Jacqueline Kennedy, who chose to wear the designer’s forgivingly cut, anemone-color coats during her pregnancy, when she made appearances on her husband’s successful presidential campaign in the fall of 1960. Jacqueline Kennedy stayed faithful to Givenchy when she accompanied her husband to a state dinner at Versailles in June 1961 and dazzled the French president, General de Gaulle, dressed in the designer’s opera coat over a ball gown of cream slubbed silk, its bodice scattered with an embroidery of naive flowers; Madame Alphand, the chic wife of the French ambassador to Washington, and a great ambassador herself for French style, had helped the First Lady orchestrate this coup.

However, Givenchy’s defining client came to him in 1953.

The designer had been expecting the great Katharine Hepburn to turn up for a fitting for her new movie and was apparently disappointed when the relatively unknown svelte gamine Audrey Hepburn appeared instead. Nevertheless, a friendship was born and his clothes for her would come to define her legendary style and Givenchy’s career. “Givenchy helped to create her image quite as much as any of her directors,” as the movie critic Alexander Walker noted. Givenchy designed the clothes that defined Hepburn’s character in 1954’s Sabrina, although the feisty eight-time Academy Award winner Edith Head took on-screen credit. By Funny Face in 1957, however, the fashion credit—couture runway sequence and all—was all Givenchy’s, and 1961’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s and 1963’s Charade continued the anointing of Hepburn as the best-dressed woman on- and offscreen. In a deft piece of marketing, Givenchy’s 1957 fragrance L’Interdit was initially created solely for Hepburn’s use and only commercialized subsequently.

“Hubert is like a tree,” Audrey Hepburn said. “Tall and straight and beautiful, in spring summer fall and winter creating and recreating loveliness. The roots of his friendship always deep and strong, the wide branches of his affection sheltering those he loves.”

Givenchy also dressed his onetime mannequin Capucine for her role in 1963’s The Pink Panther; in 1958’s Bonjour Tristesse he proved his range by dressing Jean Seberg in pretty full-skirted dresses, and Deborah Kerr in immensely chic barrel coats and the new sack silhouette that he had developed with Balenciaga.

In Memoriam: Hubert de Givenchy’s Best Looks in Vogue

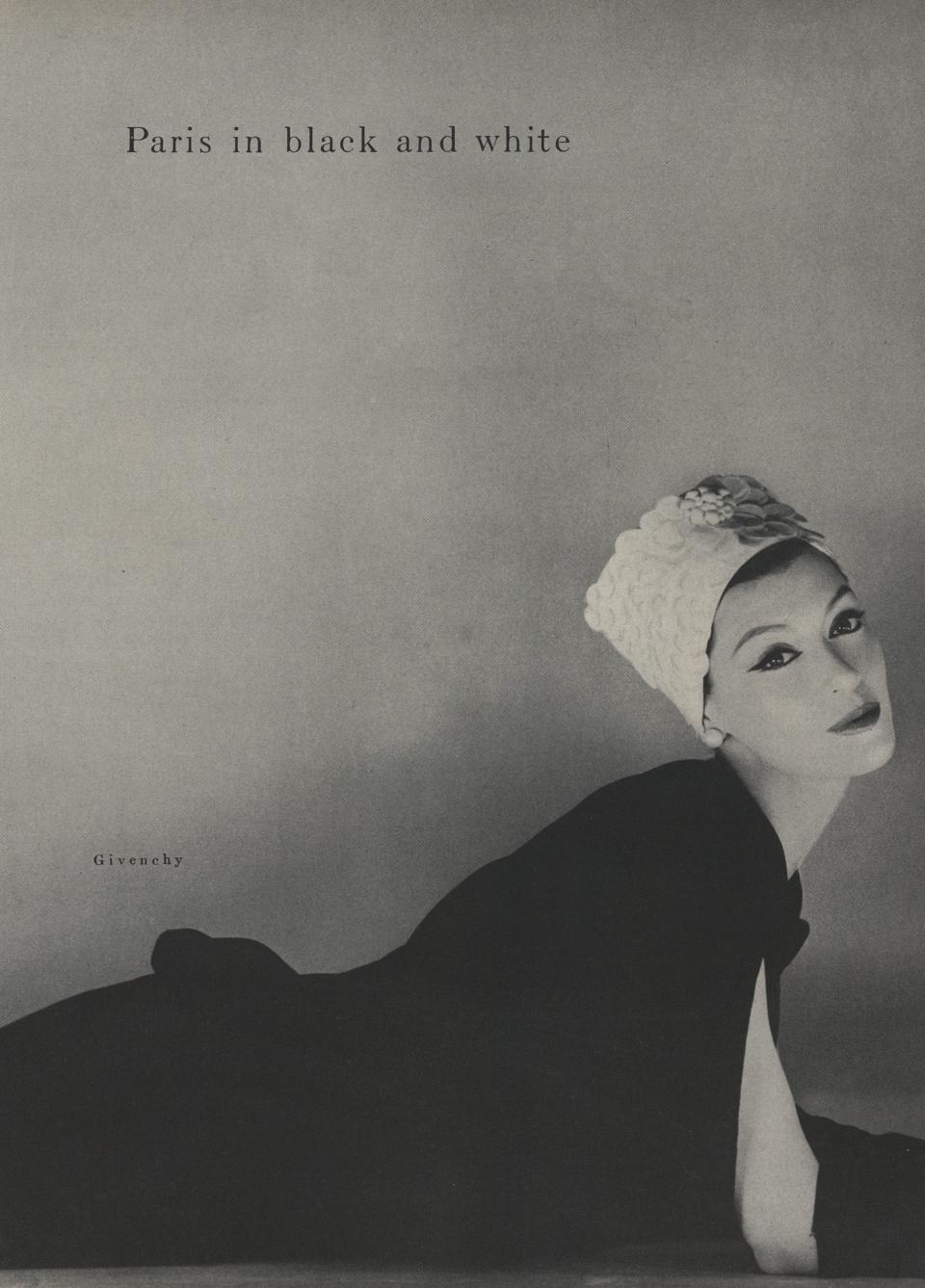

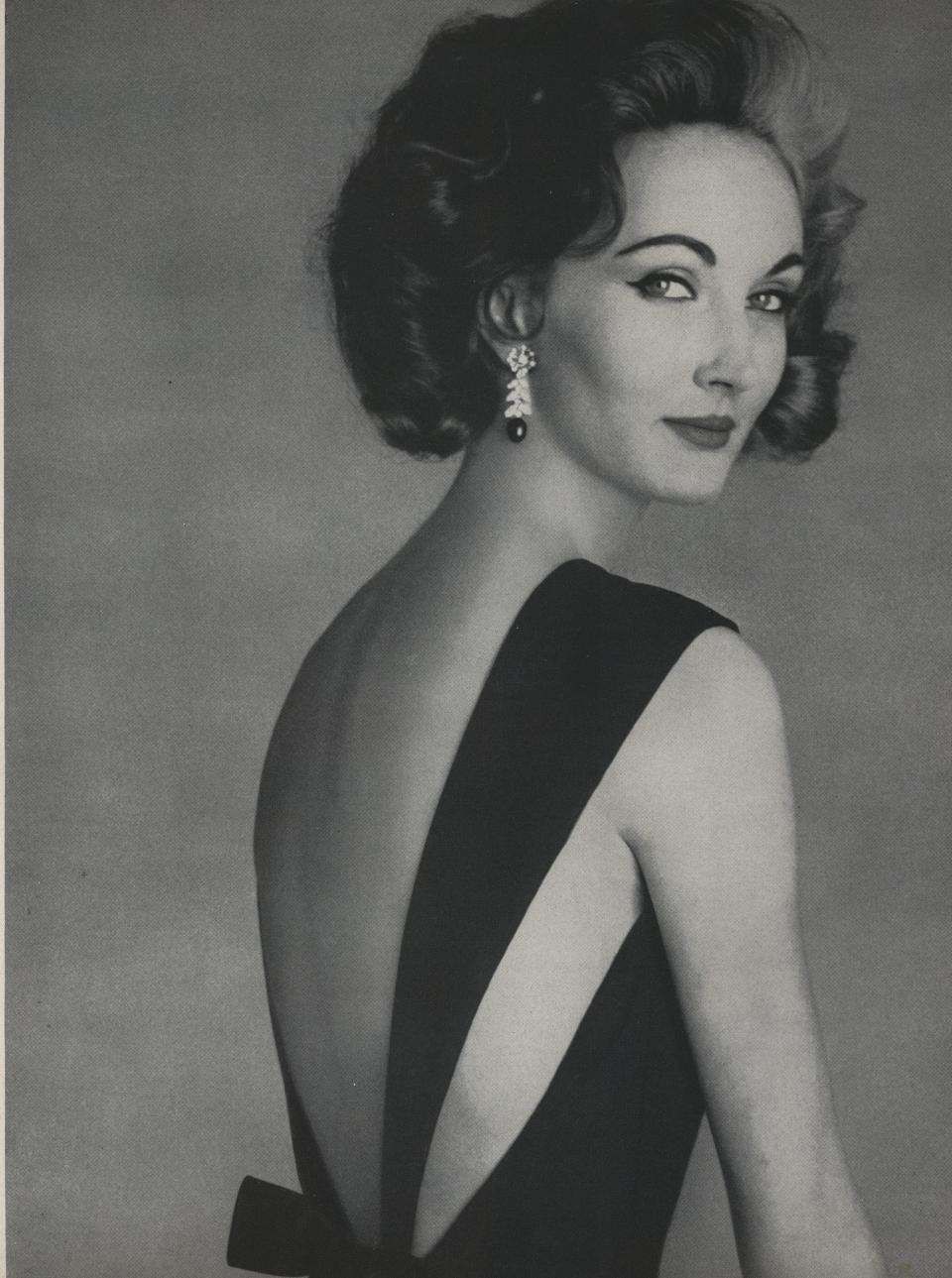

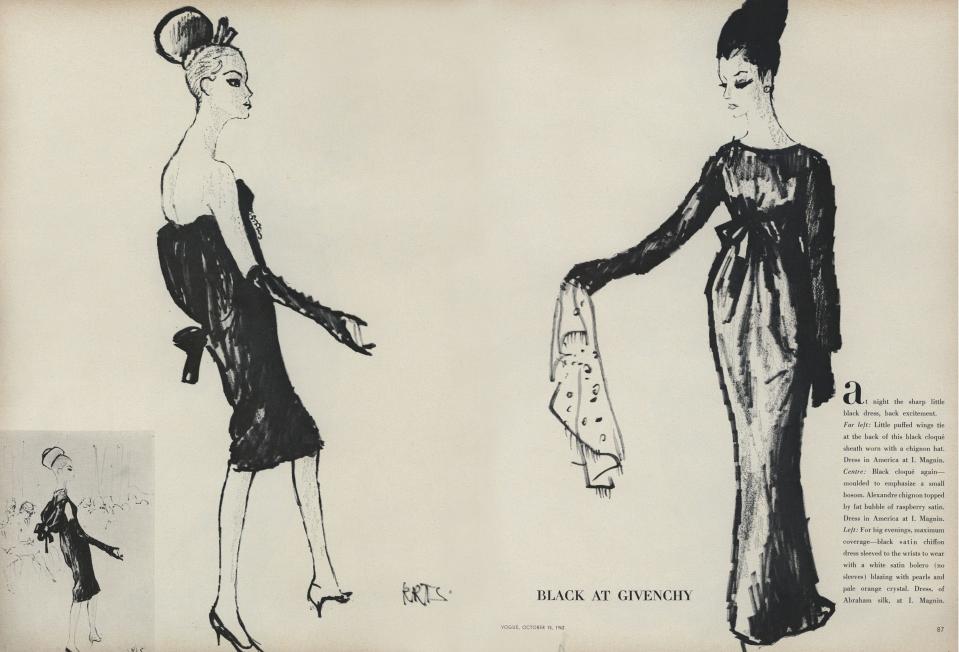

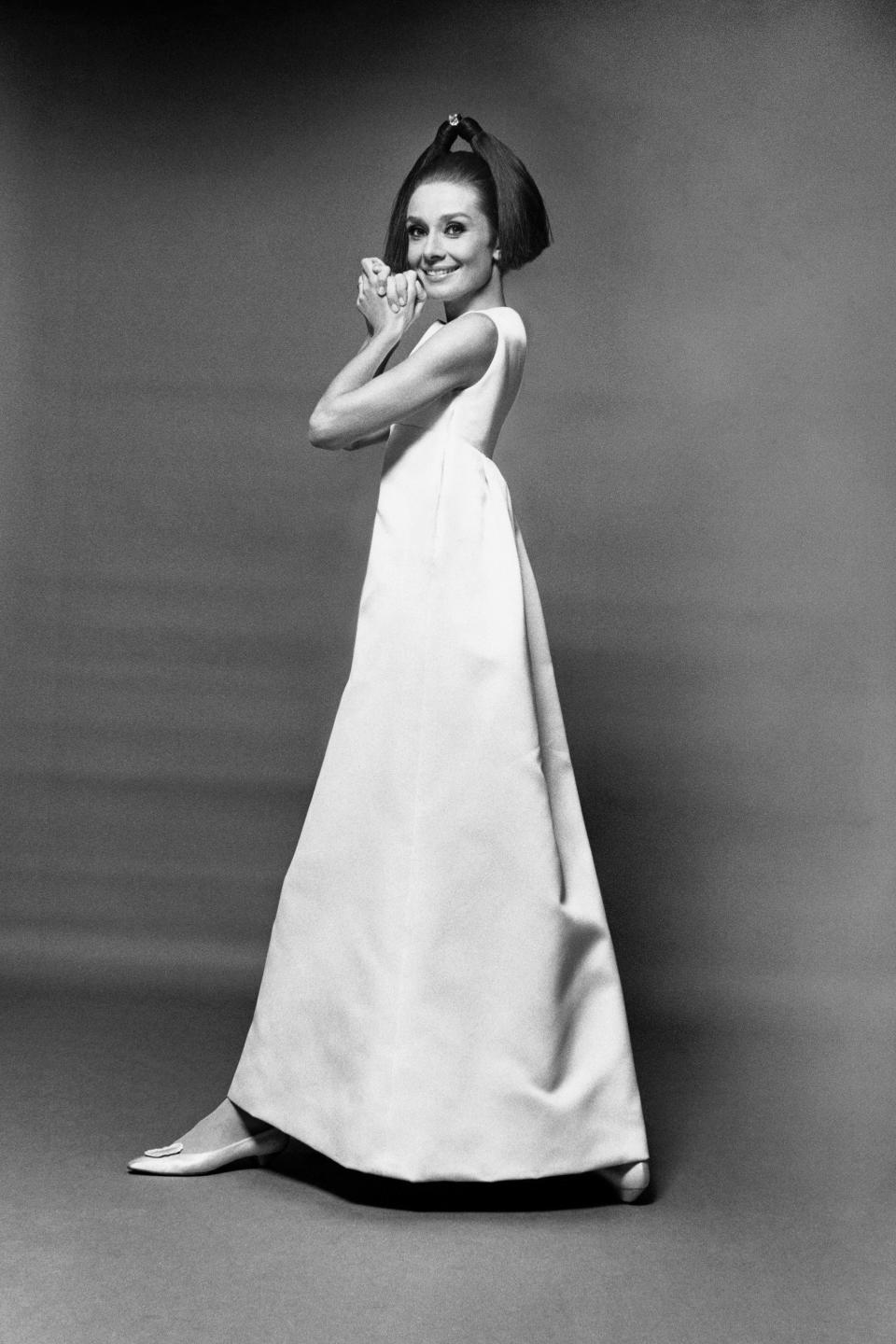

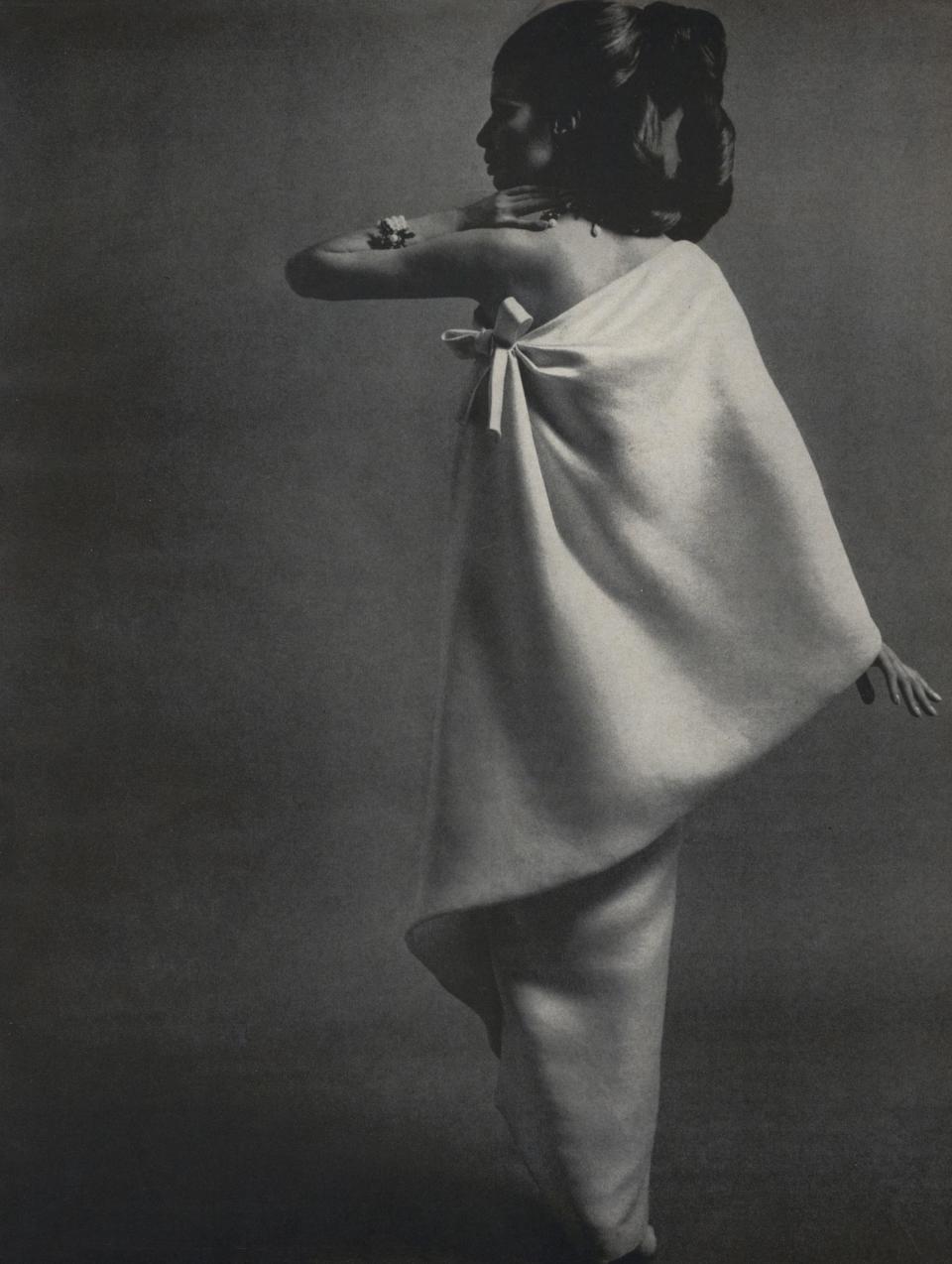

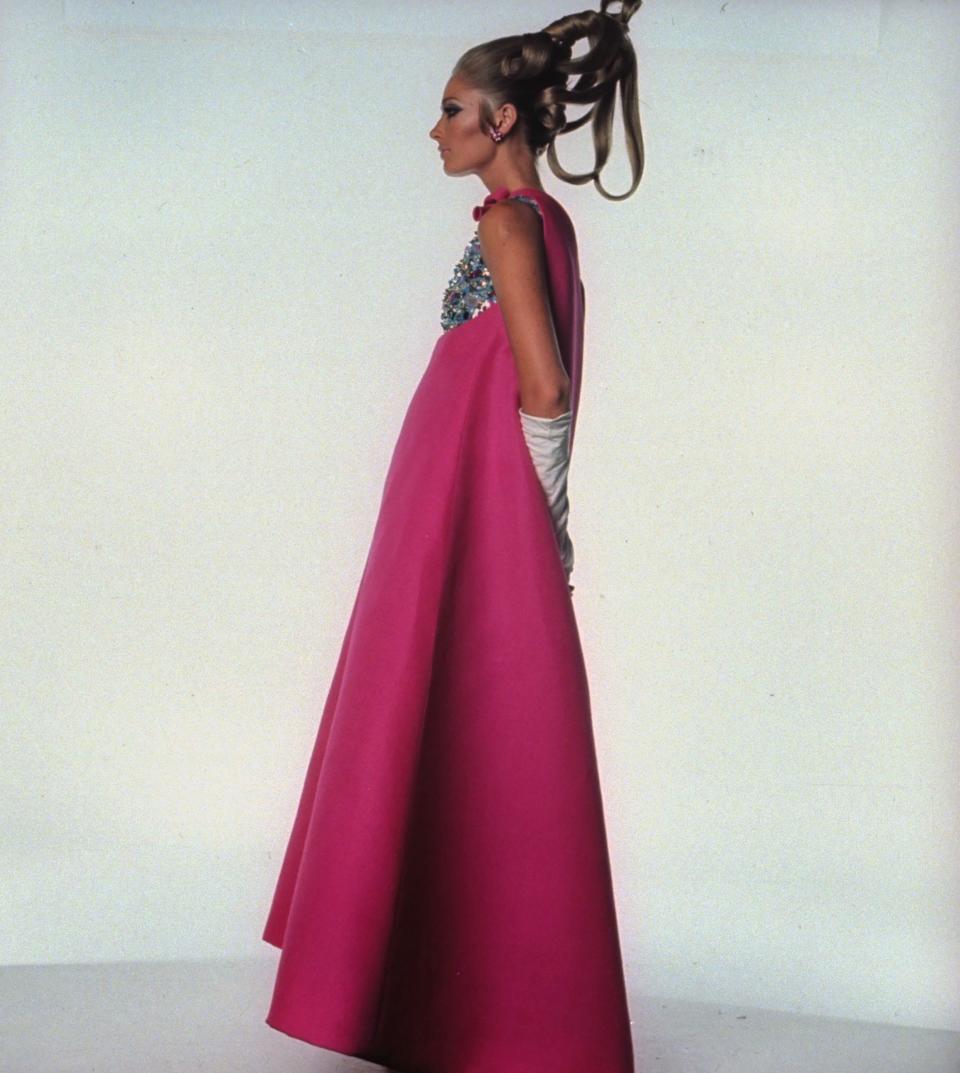

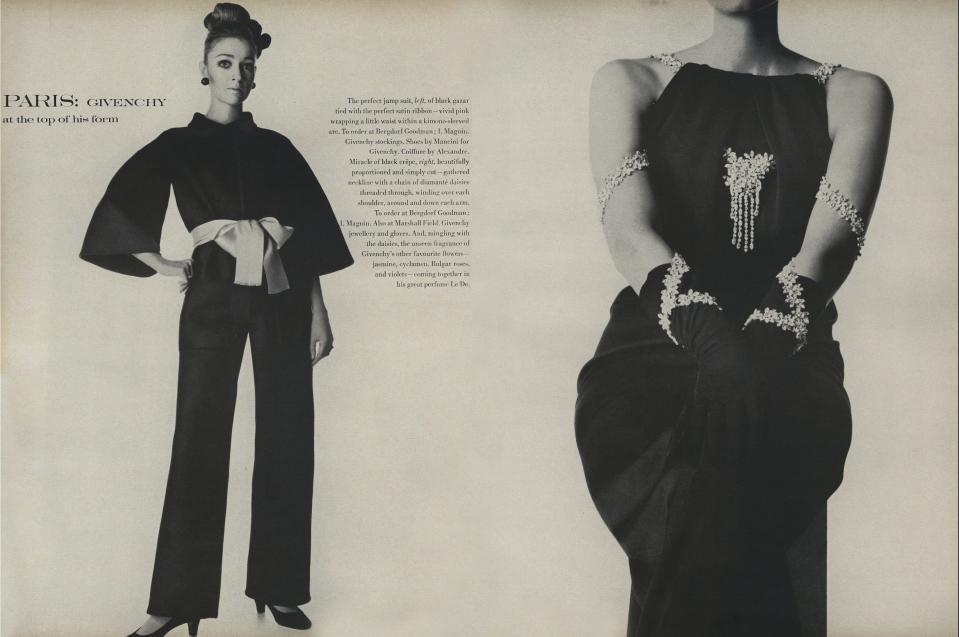

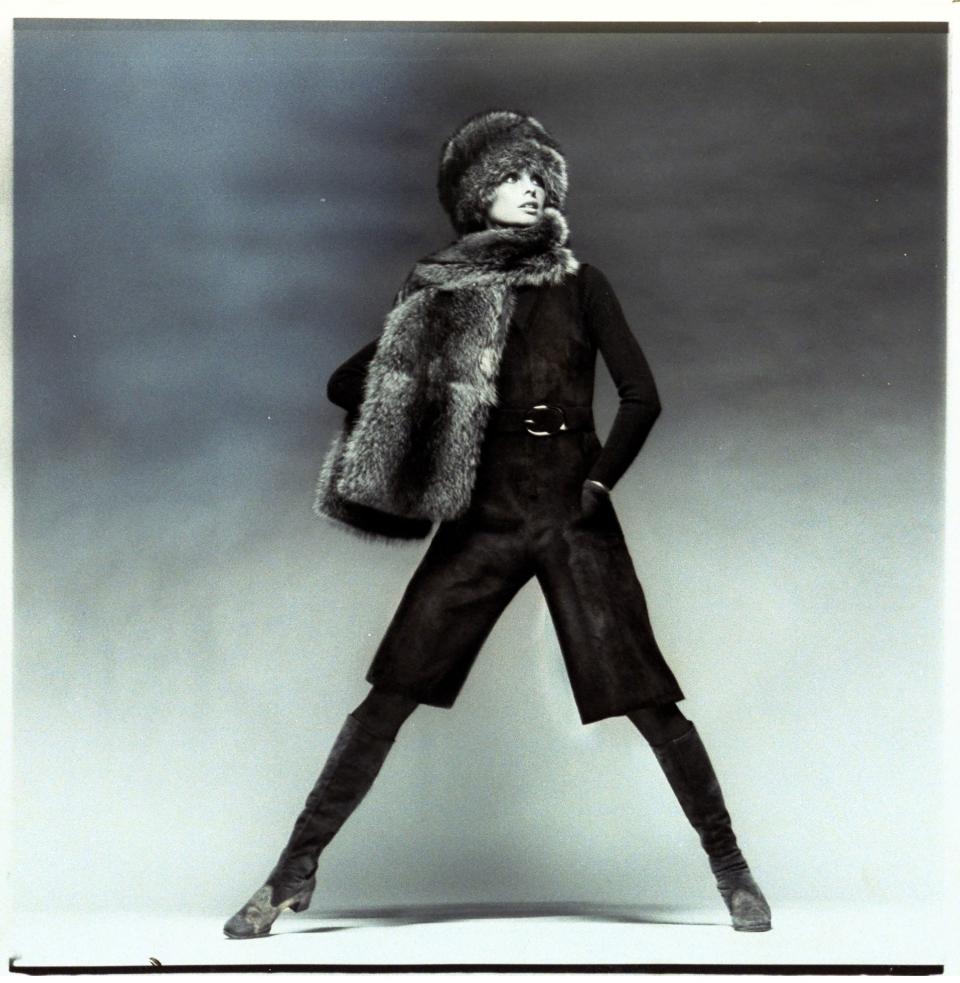

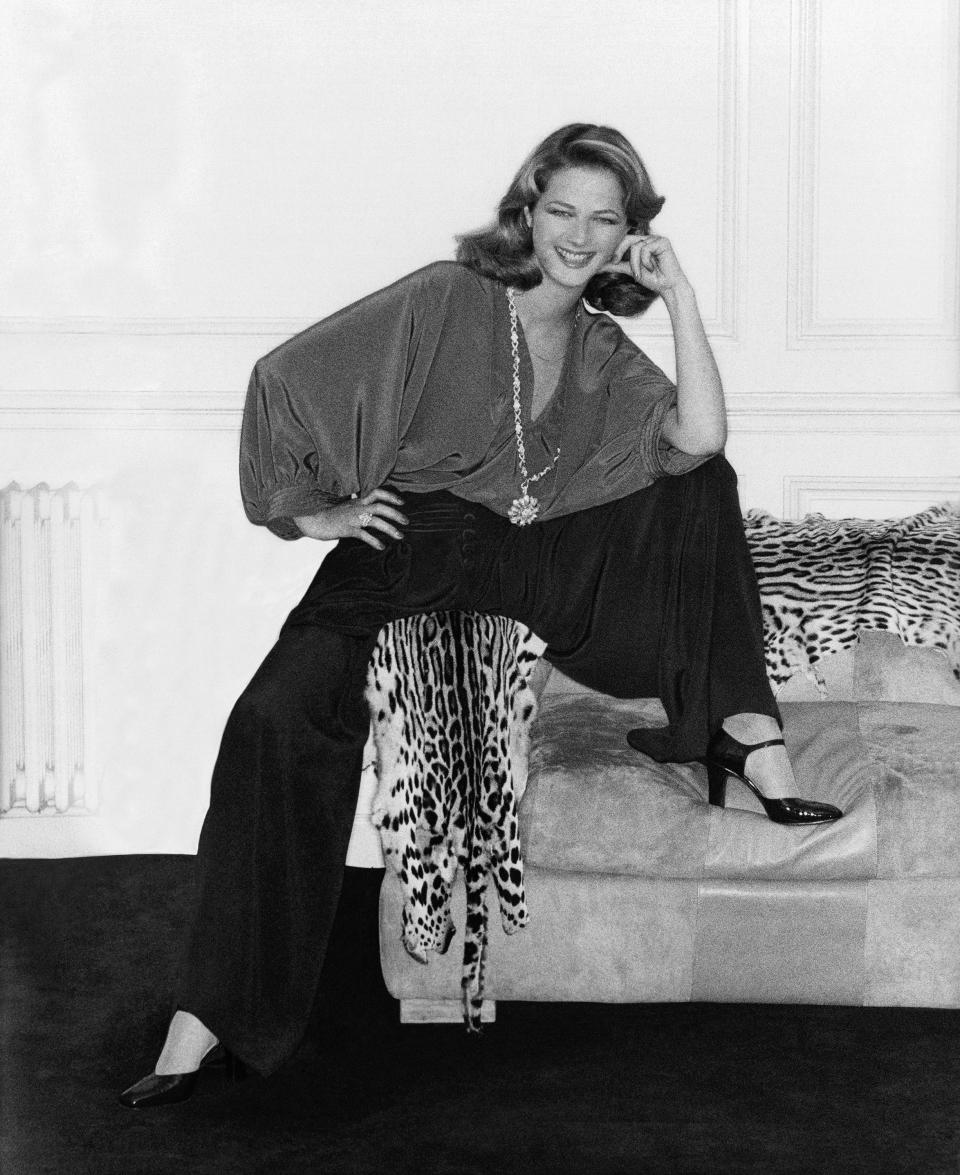

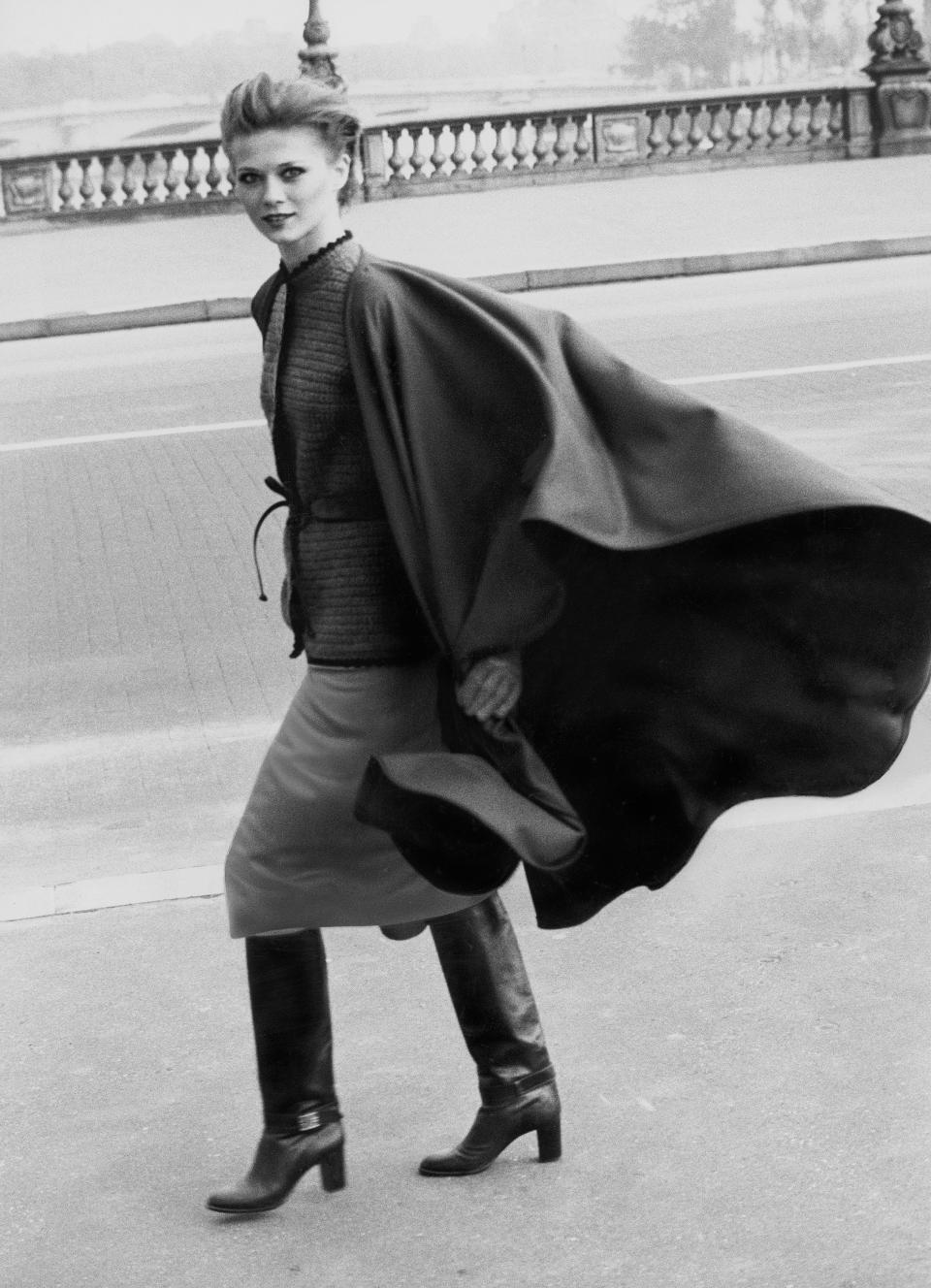

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

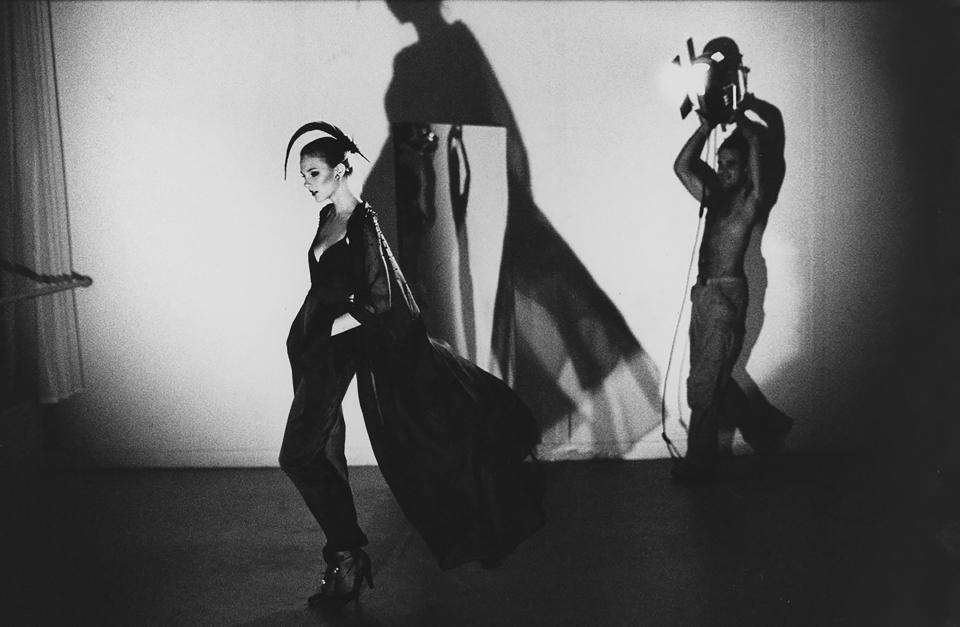

![Veruschka in Givenchy’s “wings of brilliance coat flown over [a] cropped jumpsuit.”](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/nZWcHCl19SejWh9D.z8gKg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTEwOTQ-/https://media.zenfs.com/en-US/homerun/vogue_137/73d3095b8113fd26c4b80489dae1b9e2)

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

Hubert de Givenchy’s Designs in Vogue

In 1956, Givenchy and Balenciaga broke away from the traditional Parisian fashion show schedule, as they felt that the press coverage was preempting their clients’ choices. Such was their combined power that the press had to return a month later to Paris to see what these masters had produced, and to allocate special coverage in their issues. For both designers, clients were of primary importance, and for Givenchy, America was his strongest market; his clothes, faultlessly crafted and appealingly well bred, appealed to best-dressed stalwarts, including Lee Radziwill and Deeda Blair, and invested the wearer with pedigree even when there was none.

In 1968 Balenciaga startled his clients and devastated his staff alike by unexpectedly closing his couture establishment (in a rare interview he described the couturier’s career as “a dog’s life”; Givenchy, meanwhile, called it “the most beautiful métier”). Some of Balenciaga’s legendary fitters and technicians, including the gifted dressmaker Madame Gilberte, joined Givenchy, and Balenciaga himself walked his faithful client Bunny Mellon across the street to Givenchy. Here, her orders would prove so extensive that there was a workroom dedicated entirely to the manufacture of her clothes, from the flower-themed cocktail and evening dresses to her lingerie and even her gardening clothes: Mrs. Mellon deemed it more practical to get everything from one establishment. The two became intimate friends; Givenchy had his own bedroom in Bunny Mellon’s house on Antigua, and she in the turret of the Château de Jonchet, the exquisite 17th-century French country house where he lived with his long-term partner, the fellow couturier Philippe Venet, a man of considerable charm and personal elegance himself, and a sprightlier, twinkling complement to the somewhat aloof Hubert.

In Paris they lived on two floors of a stately 18th-century townhouse on the Left Bank. I was lucky enough to visit on several occasions, notably when I was researching the 2001 exhibition “Jacqueline Kennedy: The White House Years” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and “House Style: Five Centuries of Fashion” at Chatsworth in 2017. Last year I returned to discuss the Giacometti brothers with Givenchy and startled him by producing a whopping album containing images of all the Givenchy haute couture clothes and accessories that I had been collecting for decades; when I was a very little boy the presenter of a British children’s television show went to Paris and visited Givenchy for an episode somewhat inexplicably, but thankfully, devoted to fashion. He explained to her how he had dressed dolls as a little boy, and had been taken by his mother to the couture shows, and subsequently the presenter was allowed to twirl around the salons on the Avenue George V wearing a patchwork silk evening coat borrowed from the runway collection, which I know will one day be mine. For me, it was an epiphany and my first introduction to the alchemical magic of the fashion world.

In Givenchy’s hôtel particulier the graveled entrance driveway was raked to perfection, augury of the immaculate taste on evidence within, where guests were greeted by courtly footmen and entertained in two magnificent reception rooms, one of gilded white paneling, the other a bower of deep green silk velvet, where 18th-century giltwood chairs signed by the great cabinet makers were slip-covered in starched white linen for the spring season, and Boulle cabinets and desks were set on the waxed parquet de Versailles floors. Through the tall French windows in the second drawing room could be glimpsed the formality of controlled, low box hedging and white rosebushes that hinted at the designer’s passion for gardens in the grandest French manner. This passion found even more elaborate expression in the grounds of Le Jonchet, a superb house of defining taste and almost intimidating elegance, with pale beige Cubist Braques and Picassos on the walls, and bronzes arranged on tables specially commissioned from Diego Giacometti. (The designer’s remarkable 21-piece ensemble of Giacometti commissions for the house was sold last year at Christie’s, the auction house of which he was president, for a princely $40 million.)

Givenchy retired from fashion in 1995. For his final bow he appeared on the runway with his atelier, the tailors and dressmakers all dressed, like him, in the white pique lab coats that they wore—like surgeons or scientists—to create their masterworks. It was a powerful end-of-an-era moment.

In retirement, Givenchy had a distinguished second chapter with Christie’s, and devoted himself to the legacy of his mentor, creating the Cristóbal Balenciaga Museoa in the village of Getaria on Spain’s Basque coast, where the designer was born, to showcase his work. Givenchy’s own legacy, inextricably entwined with the visual image of Audrey Hepburn, is of a life dedicated to the pursuit of elegance and aesthetic perfection, a golden proportion in all things.