In Ecuador election, strongman Correa's legacy on the line

QUITO, Ecuador (AP) — In a poor neighborhood on the outskirts of Ecuador's capital, the sleek glass-and-steel Docente Calderon public hospital rises above a frenzy of cinder block homes. Inside, patients who used to have to travel an hour to the nearest hospital and wait in line all day for sub-par treatment now get state-of-the-art care.

"It used to be you almost had to beg to get attention. Now they take very good care of me," said William Rezabala, who was undergoing dialysis in a sparkling-clean specialist ward whose serenity is interrupted only by the beep-beep-beep of medical equipment.

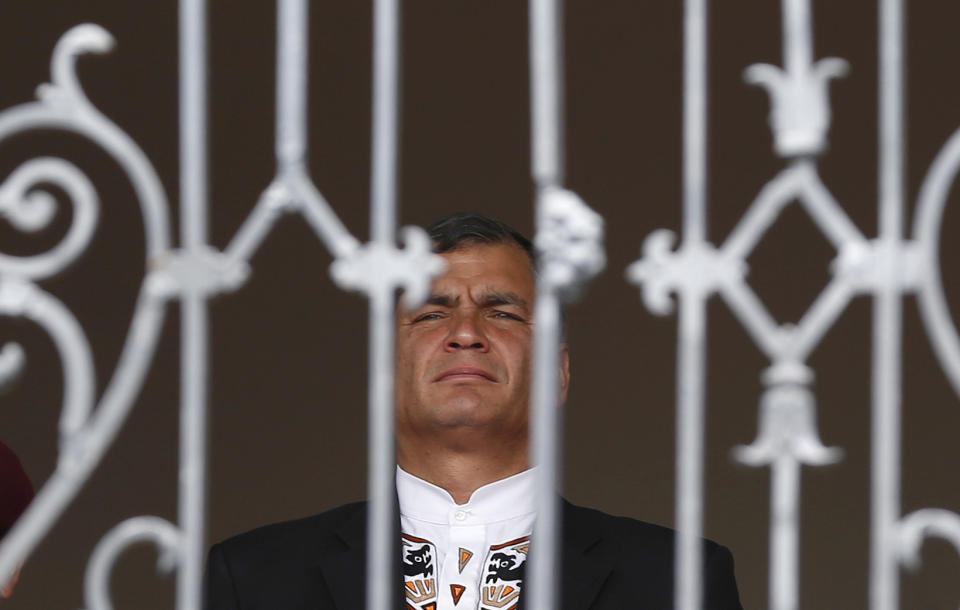

The hospital, inaugurated in 2015, is one of the crown jewels of an infrastructure buildup that has endeared President Rafael Correa to millions of poor people in this Andean nation. Now, as his presidency comes to an end, Ecuadoreans are asking what will come of the economic and political stability they've come to cherish, especially in light of a deep recession.

For the first time in a decade, Correa won't be running when Ecuadoreans go to the polls Sunday to pick a president. Although congress in 2015 approved a constitutional amendment lifting presidential term limits, the leftist leader rejected calls by supporters to run for a fourth time.

Instead, he has been feverishly crisscrossing the country inaugurating public works with the hopes of handing the torch of his "Citizens' Revolution" to his preferred successor, former Vice President Lenin Moreno. Polls say Moreno is leading the field of eight candidates with support ranging from 28 percent to 32 percent, but likely lacking a big enough edge to avoid a runoff election against his nearest challenger, currently Guillermo Lasso, a conservative former banker. To avoid a runoff a candidate needs to win more than half of the votes or 40 percent with a 10-point lead over his closest rival.

Even if he's not on the ballot, Correa's legacy is very much on the line.

Love him or hate him, most Ecuadoreans credit Correa with delivering stability after a tumultuous period that saw a musical chairs of eight presidents in a decade and an economic and banking collapse that forced Ecuador to abandon its own currency and adopt the U.S. dollar. But he did so with an iron hand that has silenced or punished critics among the press, opposition and judiciary.

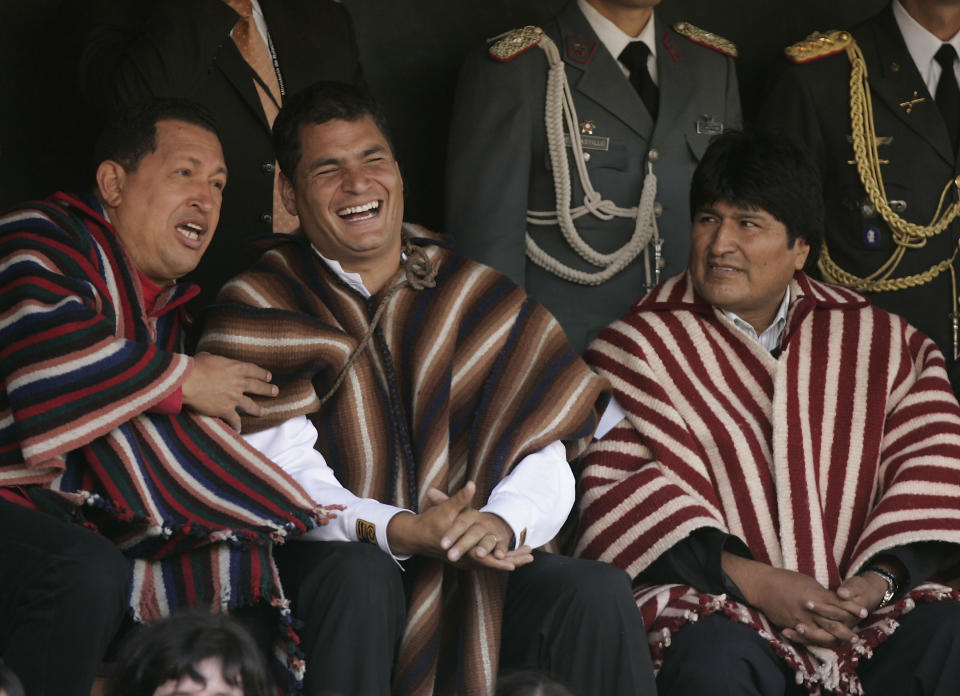

A European and U.S.-trained economist, Correa was enough of a pragmatist to never seriously challenge dollarization even while identifying himself as a "21st century socialist" and cozying up to the late Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez. He also leveraged an oil boom and loans from China to build roads, schools and other projects that have transformed Ecuador.

Docente Calderon is one of 15 hospitals built by the government in the last six years at a cost of almost $500 million. It serves a community of 500,000 people.

"Hopefully the next president will keep all these beautiful things running," said Ali Aysin, a 70-year-old patient who emigrated two decades ago from Turkey.

But as oil prices dropped, Ecuador's boom fizzled out, prompting calls for change. Mired in recession, Ecuador's economy will contract 2.7 percent this year after shrinking a similar amount in 2016, the International Monetary Fund forecasts. Last year's devastating 7.8-magnitude earthquake exacerbated the fiscal woes, leading to layoffs and payment delays at state-run companies that have rippled throughout the economy.

Regardless of who wins the election, many analysts predict the next president will have to turn to the Washington-based IMF for a bailout loan to stay current on a foreign debt that has quadrupled during Correa's tenure.

"Ecuadoreans love to rave about the roads and rant about the economy," said Risa Grais-Targow, a Eurasia Group analyst.

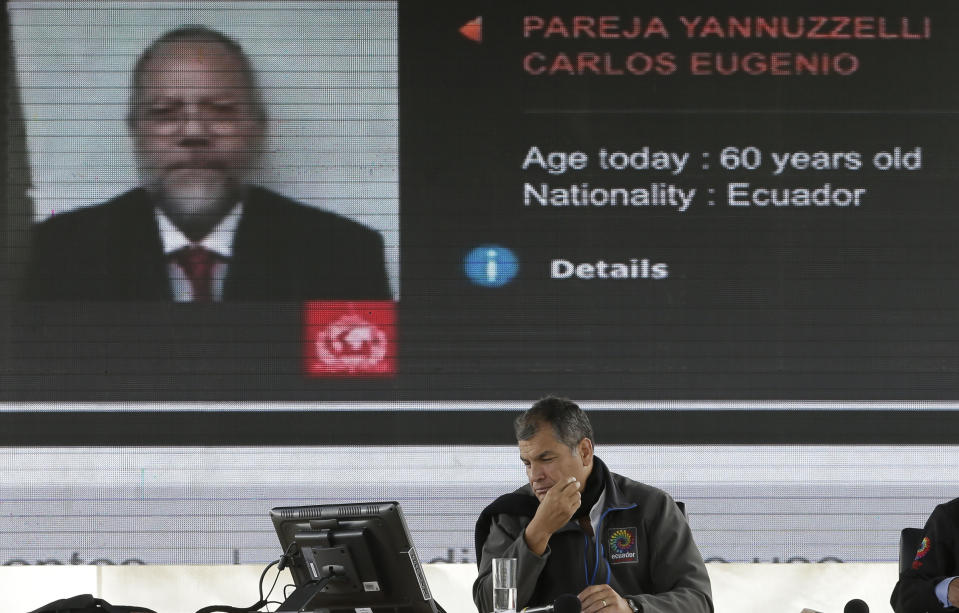

Increasingly many are also wondering whether the oil bonanza was pocketed by corrupt officials.

Throughout the campaign, Moreno has had to defend his running mate, current Vice President Jorge Glas, against allegations of graft during his time overseeing the state-run oil company. This month, a leaked video appeared on social media of a disgraced former Cabinet minister taking a lie detector test and accusing Glas of taking some of the $12 million in bribes paid to PetroEcuador for construction of a refinery. Glas has denied any wrongdoing.

But even Correa's critics recognize he has improved Ecuadoreans' self-esteem. All of the candidates competing to succeed him pay some degree of homage to his legacy, with talk of creating jobs and spending resources more wisely, not dismantling dollarization or rolling back the social programs Correa is credited with expanding.

Correa says he plans to move to Belgium, where his wife is from, and spend time strolling the streets and dining out with his family without being hounded by journalists. "They are delights that you lose in this job," he recently told the local media.

But if things don't work out in Ecuador, nobody expects the 53-year-old to go away completely.

He has warned Ecuador's opposition that his political retirement could be short-lived.

"If they misbehave, I'll run and defeat them again, so the best thing is for them to behave."

___

Associated Press writer Joshua Goodman in Bogota, Colombia, contributed to this report.