It was home to earth's largest building. Now, K-25 workers will reunite in Oak Ridge

Since the massive uranium enrichment buildings at the K-25 site in Oak Ridge were demolished, the memory of the place has been left to the K-25 History Center and the thousands of people who worked there.

Those two repositories will come together as hundreds of former K-25 employees travel to the history center for a reunion April 27, the first reunion of its kind for K-25, once home to the largest building in the world.

The site has been known by many names in its 80-year history: the Oak Ridge Gaseous Diffusion Plant, the East Tennessee Technology Park and the Heritage Center and Horizon Center. For those who worked there, it will always be known as "K-25," its code name from the Manhattan Project.

The code names Y-12 and X-10, which became Oak Ridge National Laboratory, are widely considered arbitrary and ambiguous. K-25 had a more solid origin. The "K" stood for its original developer, the Kellex Corporation, and the "25" was common shorthand for uranium-235, the explosive isotope produced in Oak Ridge for the first atomic bomb.

After nearly two decades of deactivation and demolition, all the major buildings at the site were gone by 2019, but the pandemic prevented workers from reuniting to share memories of the place.

That's why Pam Toon and Brad Parish teamed up to plan this reunion. In a little over a month, their vision for a small gathering ballooned into a big-tent event with sponsors, food trucks, a dessert table and over 450 planned attendees.

The pair, who both worked and met their spouses at K-25, say news of the reunion spread quickly online. They have heard nothing but excitement from close-knit former employees who can't wait to be together again.

Of course, the site won't look like it once did. Where five massive gaseous diffusion plants once stood, there is a large brownfield site that could become home to nuclear power startups and a general aviation airport. It's not the highly classified nuclear site it once was.

"The cool thing for a lot of these people is they have probably never driven their personal car on site," Parish told Knox News. "They can actually drive around a lot of the site at this point. ... A lot of the other buildings that we did things in, they're just not there anymore."

Toon and Parish started working at K-25 in the late '80s and early '90s, shortly after its gaseous diffusion operations had been shut down in 1985.

Toon worked in security at K-25 for over 30 years, including a stint as president of the guards' union. Parish worked in waste management and training. He went on to become chairman of the Community Reuse Organization of East Tennessee, or CROET, the group that facilitated the transition of K-25 from top secret nuclear site to private industrial land.

The two are full of good memories and stories from their time at K-25, even though working at a decommissioned uranium site came with daily hazards. One cleanup worker infamously fell 30 feet through a crumbling floor onto concrete and miraculously survived.

"It was literally the best job I've ever had in my life," Toon said. "K-25, for me, that's my heart."

For Toon, K-25 was the Goldilocks of the three Oak Ridge sites. The guard staff joked that ORNL was the "country club" where the most sophisticated people were. Y-12, meanwhile, was the "Alcatraz," the highest security place where the nation's stock of bomb-grade uranium is stored.

In her words, K-25 was "the land of milk and honey." Whenever guards from other sites in Oak Ridge came there, they were taken back by how friendly the K-25 staff was. They stuck together and had each other's backs.

Among the former employees planning to attend the reunion are site managers going back to the mid-'70s. The oldest confirmed attendee is 98 years old, though none of the former employees go all the way back to the Manhattan Project, to the knowledge of Toon and Parish.

For practical reasons, the reunion is limited to former K-25 and contractor employees and their caretakers and immediate family. It will take place from noon to 3 p.m. April 27 next to the K-25 History Center at 652 Enrichment St.

What was K-25 and what happened there?

K-25 was the largest of all the Oak Ridge sites, and its process for enriching uranium would ultimately prove to be the most successful.

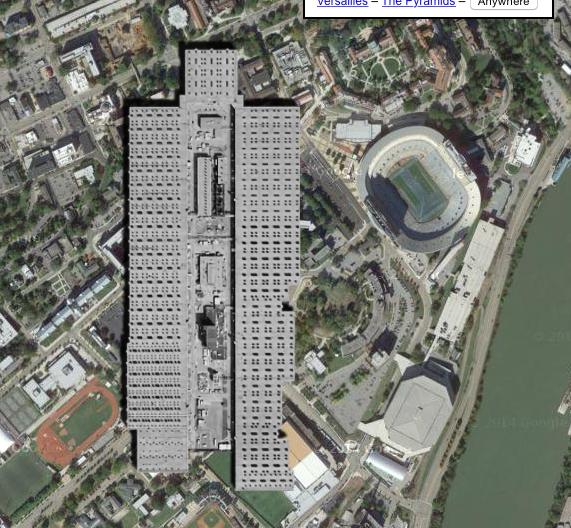

When it became fully operational in 1945, the U-shaped main process building at K-25 was the largest building in the world, holding 45 acres and over 5 million square feet under its roof. Nearly a mile long and 1,000 feet wide, it was larger than the recently completed Pentagon in Washington, D.C. Workers had to bike from one end of the plant to the other.

The technology at K-25 was cutting edge, and it faced several delays as the science caught up with the engineering. Uranium was mixed with gaseous fluorine and pressed through a porous barrier that separated the radioactive and explosive U-235 isotope from U-238.

From K-25, the uranium was fed into Y-12's machines to be enriched even further. From there, it was shipped to Los Alamos, New Mexico, where a team of scientists led by J. Robert Oppenheimer fed the fuel into Little Boy, the bomb dropped on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945.

In 1946, K-25 began producing bomb-grade uranium by itself, and the electromagnetic separation plant at Y-12 was shut down. The K-25 building became the blueprint for four other massive plants at the site – K-27, K-29, K-31 and K-33 – and gaseous diffusion plants in Paducah, Kentucky, and Portsmouth, Ohio.

During the Cold War, the U.S. rapidly expanded its nuclear arsenal to compete with the Soviet Union. All the uranium produced during the Cold War for weapons and commercial reactors was made through gaseous diffusion. K-25 and its sister building K-27 were shut down in 1964 and all gaseous diffusion operations in Oak Ridge ended in 1985.

K-25 was a historic (and dangerous) cleanup effort

It was only two years later that Toon began working at the site and Parish would follow soon after. Closing the giant buildings was the end of one chapter at K-25, but it was only the beginning of another long chapter, this time with a different theme: uranium production was swapped for radioactive cleanup.

Toon remembers patrolling every floor of the massive U-shaped K-25 building, which was full of radioactive material and was still highly classified.

"We had to walk carrying M-16 machine guns on every floor," Toon said. "When they shut it down, they had to seal all the doors. Every door was sealed on that building. Certain areas had alarms, and if we got an alarm in certain areas, we had to respond with guns drawn, because those areas were very sensitive, very highly classified."

When she first started working at K-25, Toon and the other guards didn't wear any special protective clothing to stay safe from radioactive material. That wouldn't happen until a health physics team inspected the site in the '90s and raised an alarm.

Radioactive material was only one concern. The massive buildings were also falling apart.

"Anytime you shut down something and you don't have air conditioning and heat, it's gonna deteriorate," Toon said. "At the time they shut down, they were like 'We're not going to work on it because it's going to be torn down.' So over time, the K-25 building got so bad. The roofs were caving in on it. Water was everywhere, and mold."

Stepping into the K-25 building was like stepping back in time to the 1940s. It wasn't until 2002 that the Department of Energy began deactivating the gaseous diffusion buildings with its cleanup contractor Bechtel Jacobs.

Bechtel Jacobs began demolishing K-25 in 2008 and passed the project on to its successor United Cleanup Oak Ridge in 2011. UCOR finished the job in 2013. The five main gaseous diffusion buildings were all demolished by 2016 and the historic cleanup project ended in 2020.

The cleanup is the signature achievement of the Oak Ridge Office of Environmental Management, the local arm of the Department of Energy's effort to clean up Cold War radioactive sites. Some leaders even compared the project to building the interstate system or landing on the Moon.

For K-25's workforce, it was a bittersweet moment when crews began tearing into the buildings they had worked in for decades. They had heard murmurs for years of a coming demolition, but it had become real. Toon worked at K-25 until 2019, when there was nothing left to secure. Now, she's a centrifuge operator at nearby Centrus Energy.

Reunion brings Oak Ridge community together

The overwhelming support for the K-25 reunion from the Oak Ridge community has shocked and pleased Toon and Parish. Its sponsors include Nuclear Care Partners, CROET, the Coalition of Oak Ridge Retired Employees, Big Ed's Pizza, Munsey Pharmacy, the Oak Ridge Youth Symphony Orchestra, UCOR and MCLinc – a private lab born from K-25.

Some sponsors donated door prizes. Patriot Talent Solutions donated to ensure attendees could tour the K-25 History Center for free during the event.

There will be stories galore from past K-25 managers, technicians, guards and engineers. The plant was like a small city, Parish said, with its own gas station, stores, cafeteria and fire department. Even though it's gone, it's an indelible part of thousands of lives.

Even for workers who later got sick from exposure to radioactive material, Parish expects to hear memories full of nostalgia.

"At the reunion," Parish said, "we'll probably hear all kinds of stories."

If you are a former K-25 employee and you would like to attend the reunion, you can visit k-25reunion.com and join the reunion's private Facebook group.

Daniel Dassow is a growth and development reporter focused on technology and energy. Phone 423-637-0878. Email daniel.dassow@knoxnews.com.

Support strong local journalism by subscribing at knoxnews.com/subscribe.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: What is K-25? Former uranium site workers plan Oak Ridge reunion