How a Duke professor rescued a lost jazz treasure from a forgotten cardboard box

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Somewhere on the Duke University campus, the last notes from a jazz luminary lay hiding in long-forgotten storage — a half-finished finale scratched out in pencil by the same hand that made Benny Goodman swing.

Those lost pages came from Mary Lou Williams, who honed her hard-swinging style in the nightclubs of Kansas City and refined it in the be-bop whirlwind of Harlem. When she was only 15, Louis Armstrong kissed her on the forehead, delighted by her playing.

From her debut in the 1920s, critics called Williams “a deluxe tickler of the ivories,” “one of the foremost swing pianists of either sex,” a master of swing piano who wrote tunes for Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie and herself.

But she spent her final years as artist-in-residence on the bottom floor of Duke’s Biddle Music Building, putting the coda on her long career. There, sick with cancer, she kept working on one last piece — an expansive “History” of jazz that combined ragtime, gospel and swing as ingredients in a giant stew.

And when she died in 1981, the work disappeared.

Completing a musical circle at Duke

This is the story of how a fresh and sympathetic set of ears heard a few notes of Williams’ “History” and set out to find, rescue and finish it, completing a musical circle that spans a century.

Finding and finishing it brings the largely forgotten Williams emphatically back to life, reviving an icon not only from the distant jazz past but also restoring Williams’ presence to the campus that adopted her.

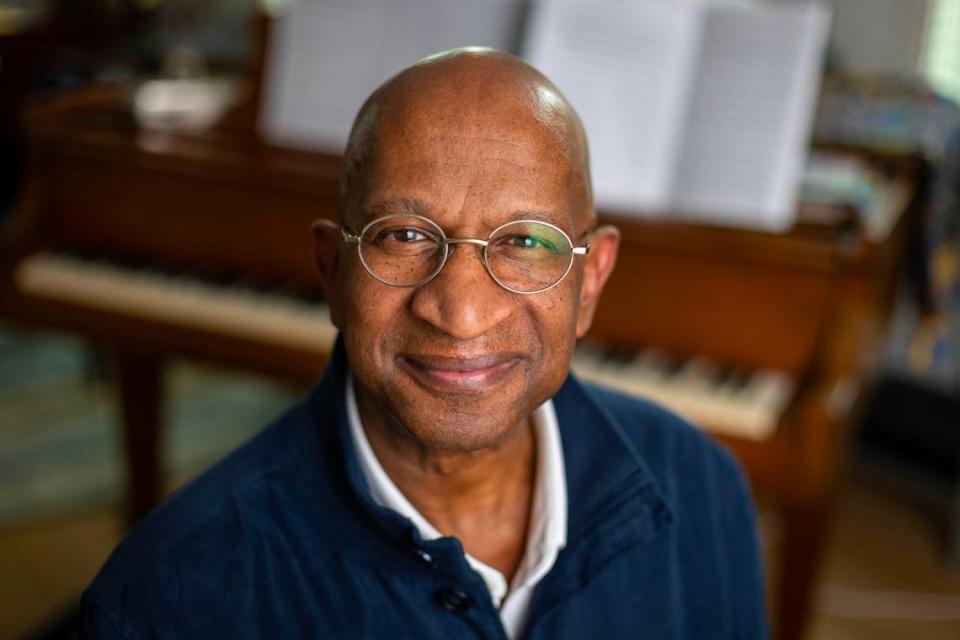

For Anthony Kelley, who discovered her “History” and filled in its considerable gaps, the experience of pulling Williams out of the past felt like uncovering a lost world.

“It was like one of those scenes from ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ when the light shines in your face,“ Kelley said. “She held this paper. This is her handwriting.”

Kelley’s fascination started in the isolation of the pandemic’s early days, when he clicked on a Williams documentary out of curiosity and time to spare. Williams does, after all, have Duke’s Black culture center named for her.

“I did know she taught here,” Kelley said from his office in Biddle. “Mary Lou Williams taught five doors down.”

In the documentary Kelley watched, Williams’ time at Duke and her unfinished history comes up only in the last five minutes. Had he dozed off on the sofa, his life would have taken another turn.

But Kelley found a quest that day. Where was this music? Was it online somewhere? Was it at Rutgers, which holds much of her collection? Was it at Duke somewhere?

Kelley was a Duke alumnus himself, and had played tuba in both the jazz ensemble and wind symphony. He had deep contacts around campus, so he asked around, hearing clues along the lines of “I think it’s in box 43 or something like that.”

The hunt took a year, but a Duke archivist turned up a cardboard box labeled no. 27 — not 43 — and inside were roughly 40 sheets of paper tied with string. The eighth notes danced across the sheets as he flipped through them.

“My teachers used to say, ‘Use pencil, because pencil holds up,’ “ he said.

Channeling Mary Lou Williams

To Kelley’s relief, Williams had supplied an outline for her history, with the subheadings scribbled in order: Intro, Suffering, Spiritual #1, Spiritual #2, Gospel, Ragtime ...

But the pages contained intimidating gaps. Sometimes Williams just wrote “Bones” for an unscripted trombone part. Her ragtime section contained music for first and second clarinets — nothing else.

So Kelley spent a year channeling. He watched every performance, listened to thousands of hours of recordings and even saw Williams’ 1973 appearance on “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” thanks to YouTube.

As he wrote, he felt pieces of his own life converging with his long-gone colleague down the hall. He was an alumnus, he had played jazz with the same people Williams knew at Duke ...

So he could follow her path. In the end, a composition for 33 parts emerged, now in rehearsal. On April 13, at Duke’s Baldwin Auditorium, it will be played for the first time.

“She was a far more daring composer than I am,” Kelley joked, imagining his partner’s posthumous reaction. “Sometimes she might think, ‘Eh, that’s a little safe.’ “

Kelley takes satisfaction that the work is no longer dormant. It lives for new ears to discover, pulling a 21st-century audience into a fading jazz history that even music students struggle to appreciate. But after a year slogging through a pile of half-finished brilliance, Kelley gained this new insight as a composer.

“Boy,” he said. “I sure wish somebody would finish my pieces for me.”