Dr. Werner Spitz, famed forensic pathologist, wrote the book on death

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Dr. Werner Spitz spent a lifetime chasing death — and, this week, finally caught up to it.

By any measure, Spitz had lived a long time — 97 years — and no doubt will be remembered most as one of the nation's leading forensic pathologists, someone who had dedicated nearly his entire adult life to understanding how — and why ― people died.

Spitz, who also was a Wayne State University Medical School professor, literally wrote the book on investigating unnatural and suspicious loss of life.

"To many in the field, and to many others, he was the preeminent authority in the science of forensic pathology," Wael Sakr, the WSU med school dean, said. "His work, the recognition he achieved and his willingness to discuss his work led many to explore the science and to enter the profession."

More: World-renowned forensic pathologist Dr. Werner Spitz dies at 97

Spitz's own end, however, was uneventful. The internationally known medical professional's death came Sunday, a result of natural causes after a brief illness. He slipped away surrounded by his family, said Dr. Daniel Spitz, one of Werner Spitz's three children.

The deaths Spitz examined included thousands of ordinary metro Detroiters — homicide victims and drug addicts among them — and quite a few famous folks, too: a slain U.S. president, an assassinated prime minister, an actress, a child beauty pageant princess, and other celebrities.

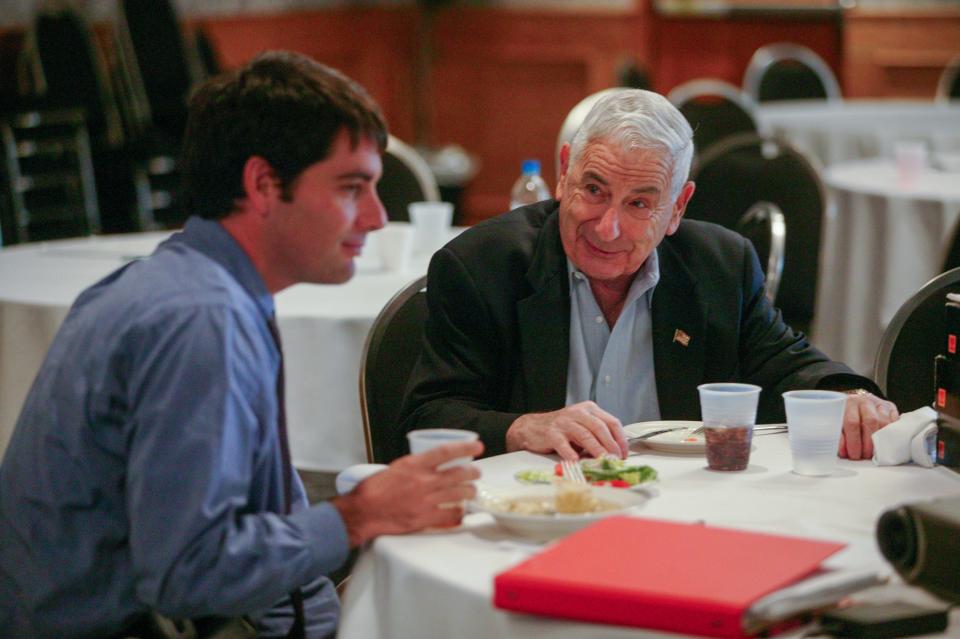

"There was no one like him, anywhere, ever," said Michigan trial attorney Ven Johnson who worked with Spitz for more than 35 years; and, just last year, put him on the witness box. "This guy, by far, was the No. 1 forensic pathologist in the world. You look at his cases, both criminal and civil."

Johnson described Spitz as a thorough investigator, following the facts and evidence wherever it took him. He also was a "down-to-earth" person who managed to remember the names of everyone in the firm, and had a special "glow of positive energy and heart that juries just loved."

Spitz — Johnson, and others who knew him, said — wasn't much for golf or gardening, but he had a passion for work, even into his 90s. And any spare time he had, his relatives added, was devoted to spending it with friends and family, often regaling them with fascinating stories, sometimes over a hearty steakhouse dinner.

'Death waits for no man'

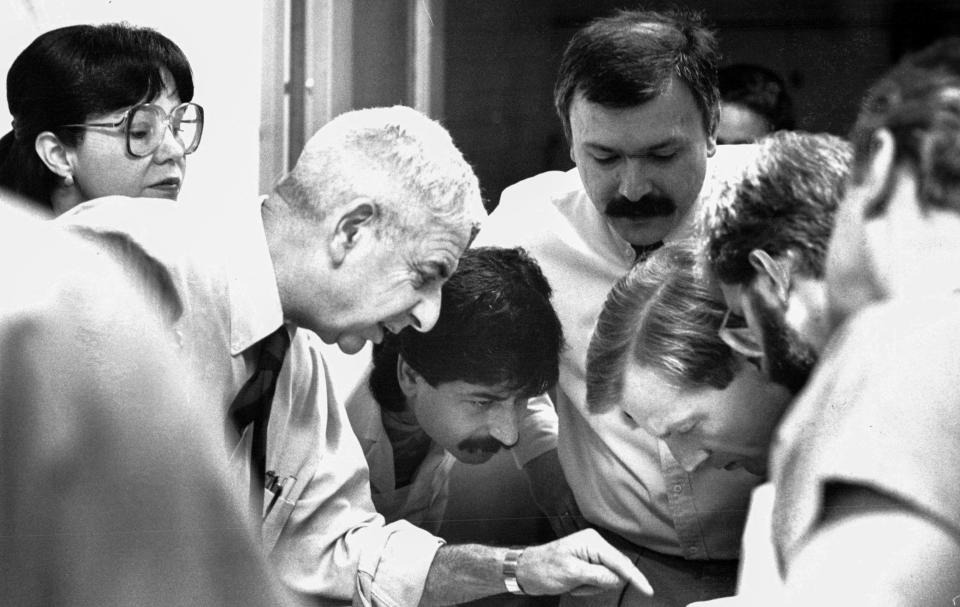

Spitz's career highlights are well documented in newspaper and magazine reports.

For decades, and even right up until the last years of Spitz's life, journalists, prosecutors, and defense attorneys sought his medical counsel and time to interview him.

In 2022, Time magazine — the sort of periodical with gravitas and reach that you'd want to record your legacy — printed a comprehensive profile of Spitz that pointed out how, even in his 80s, he was jet-setting to examine dead people's bones.

"Death," the national publication declared, "waits for no man — especially not a forensic pathologist."

The 2,700-something word article described how, on Christmas Eve in 2008, Spitz got a call seeking his opinion on the slaying of 2-year-old girl, Caylee Anthony. Afterward, he hopped on the next flight to Orlando to look at the toddler's skeletal remains.

The article also featured photos of an aging, but dapper-looking, Spitz, then 95 years old, in a red tie and sports coat. In one image, he was looking through a magnifying glass like a detective might. The article's title even referred to Spitz as a "medical detective" adding he had examined many "famous cases."

In the Anthony case, law enforcement officials had sought Spitz out on a holiday because they theorized Caylee's mother, Casey Anthony, took her daughter's life and needed Spitz to determine what the medical evidence showed.

Anthony's murder trial, like so many others of which Spitz was a part, captivated the nation.

Time called Spitz, who was a Grosse Pointe Shores resident, "a founding father of modern forensic pathology." Spitz, it added, "has seen the discipline grow from its infancy" to what is now, including the well-known theme of several popular TV dramas.

The magazine also noted that Spitz's book — "Spitz and Fisher's Medicolegal Investigation of Death: Guidelines for the Application of Pathology to Crime Investigation," which was co-edited with Daniel Spitz, who also is a forensic pathologist — is "considered the gold standard in the field today."

Fleeing a growing threat

Werner Uri Spitz was born in 1926 to a Jewish family in Stargard, what was then Germany, and is now Poland. Both of his parents, Siegfried and Anna Spitz, were physicians, and the family fled to Israel as anti-Semitism grew.

Spitz told the Free Press in 2004 that in Israel, he started working as a youngster in a medical examiner's office. His father found him the job, which was, at first, to fetch lunches and keep them swept up. But gradually, Spitz said, he received more responsibilities, including helping with autopsies.

One of those autopsies, he said, was of Morris Meyerson, the husband of Golda Meir, the future Israeli politician and prime minister. After that, he was hooked on the emerging — and macabre — science of understanding death.

Spitz said he found the forensic process fascinating, "piecing together a story using the shell of a human who could no longer explain why he or she died." He later started his studies at Geneva University in Switzerland and then attended the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

In 1959, Spitz came to America to work in Baltimore.

Two years later, he returned to Germany, and then, in 1963, came back to the United States a second time aboard a ship. On the way, he heard the news that Kennedy had been shot and killed. Spitz was later asked to join the assassination commission that determined Lee Harvey Oswald was the gunman.

In a 2013 interview with the Free Press, Spitz recalled that it shook him to hear Kennedy had been killed. And, he said, even 50 years later, he still got "all choked up" thinking about it. Spitz said that in his expert medical opinion, Oswald fired three shots, and only two struck the president.

In a defense of Detroit

Spitz worked on many other well-known court cases.

In addition to the Casey Anthony trial, Spitz also testified as an expert in the notorious case in which Phil Spector, a record producer, was charged with killing an actress in 2000; and in the civil trial of O.J. Simpson, the American football player and actor accused of killing his ex-wife and who died last week.

Spitz also was consulted in the 1996 death of JonBenet Ramsey, the child beauty pageant, who, at 6, was slain in her Boulder, Colorado, home. And, earlier in his career, Spitz was involved in the investigation of the 1968 assassination of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.

In 1974, Spitz, as the Wayne County Medical Examiner, wrote to the New York Times, responding to a report on Detroit's high murder rate and its causes, particularly the role of narcotics. The Times — in a Sunday edition — published Spitz's letter.

"You specified that 84 out of 751 homicides in Detroit in 1973 were the direct result of the drug wars," Spitz wrote. "This is correct, but this number in no way reflects the number of narcotics‐related homicides in our city."

Spitz defended Detroit, which back then, was referred to in the news media as the "Murder Capital of the World." Spitz explained to the Times there are many reasons why addicts are killed, and "there is no way to ascertain how many of the deaths" are "actually homicides."

His point: The interpretation of data was misleading and more needed to be done to address drug abuse.

"While authorities agree that narcotics are a major cause of crime in America, the degree to which drugs are a problem is not recognized," Spitz wrote. "And as long as homicides are classified as resulting from a domestic argument when there is narcotics paraphernalia lying on the kitchen table, we shall be unable to direct our resources toward fighting the narcotics problem."

Simpson 'fingernail theory'

More than two decades later, in 1996, Spitz testified for the prosecution in the civil suit alleging that Simpson killed his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend Ron Goldman. Spitz concluded the small, semicircle cuts in O.J. Simpson's left hand were nail marks caused by Simpson's ex-wife fighting for her life.

The so-called "fingernail theory" made national news.

But Michael Baden, a former chief medical examiner in New York City who Spitz would later work with on a different case, disagreed with Spitz's findings, concluding it was unlikely that a single person could have killed both victims alone.

In late 2007, the New York Times asked Spitz to weigh in on the assassination of Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, who was killed at a political rally. It was unclear whether she was shot, hit by shrapnel from a suicide bomb, or died from hitting her head in the vehicle in which she was riding.

Her death, some thought, was similar to Kennedy's.

Spitz told the Times he "could not understand why the government did not try to quench 'the thirst of the Pakistani people to know the facts, because they are all angry, and if you confronted them with the facts, maybe the anger' would disappear."

Spitz, the Times reported, suspected Bhutto died after being hit by a bullet fired from a high-powered rifle.

An important police role

And, as recently as two years ago, Spitz still was taking calls from attorneys.

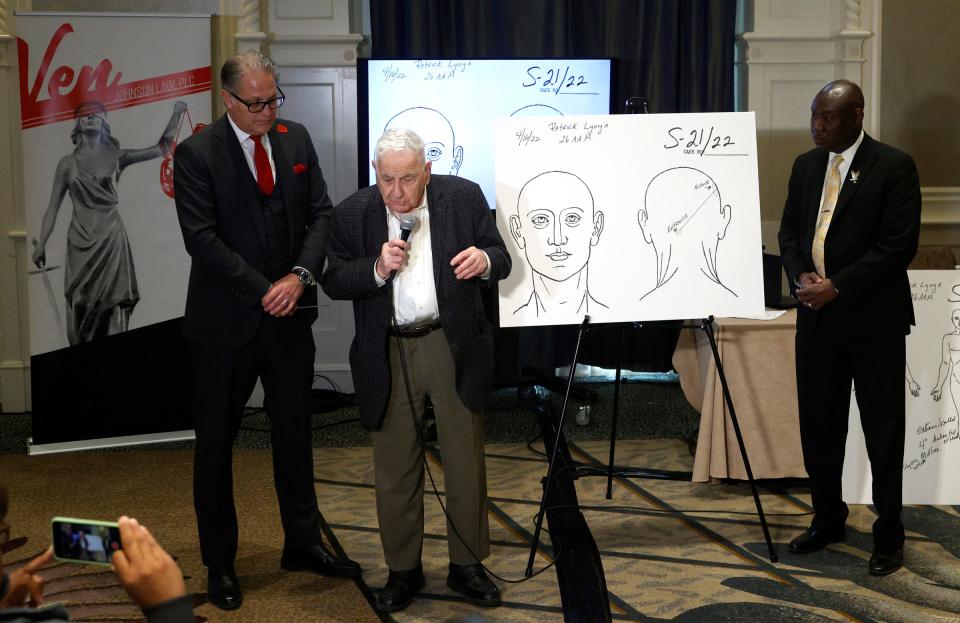

He was hired to give an opinion on how Patrick Lyoya, a Black man who was shot by a white police officer, died. Spitz, then-95, spoke in front of reporters and TV cameras at a news conference at the Westin Book Cadillac Hotel in Detroit.

Spitz, along with Baden, his sometimes-rival, offered a joint opinion of the controversial Michigan death, explaining that their medical findings indicated that Lyoya, 26, was shot in the back of the head with a large-caliber bullet.

"There’s no question what killed this young man," Spitz said in his distinct accent with characteristic certainty. The forensic pathologist added that Lyoya, a refugee from the Democratic Republic of the Congo "died as a result of a single gunshot wound with entrance wound in the back of the head."

Spitz, Macomb County Executive Mark Hackel said Monday, often played an important role with police.

Hackel told the Free Press he has known Spitz since 1981. Before he became Macomb County Executive, he was in law enforcement. And it was his first week on the job as a dispatcher. Hackel said he took a call about a Macomb Township slaying involving a woman and three children.

Over the years, Hackel said, Spitz showed him how vital a forensic pathologist is to a community and to understand that a medical examiner not only looks at the body "to determine cause of death" but also helps analyze the crime scene.

He 'comforted and educated'

And while Daniel Spitz said his dad is probably best known for his work on high-profile criminal cases and people, over the decades his father, as the medical examiner for Wayne and Macomb counties, performed and oversaw thousands of autopsies, some routine, others complex.

With each one, Daniel Spitz told the Free Press, his father "comforted and educated" families.

Spitz, who followed in his father's footsteps into the medical profession, said his dad would try to answer questions from loved ones, try to create a greater understanding of what happened, and try to offer solace and support through grief, which, often was a result of the most horrific and tragic circumstances.

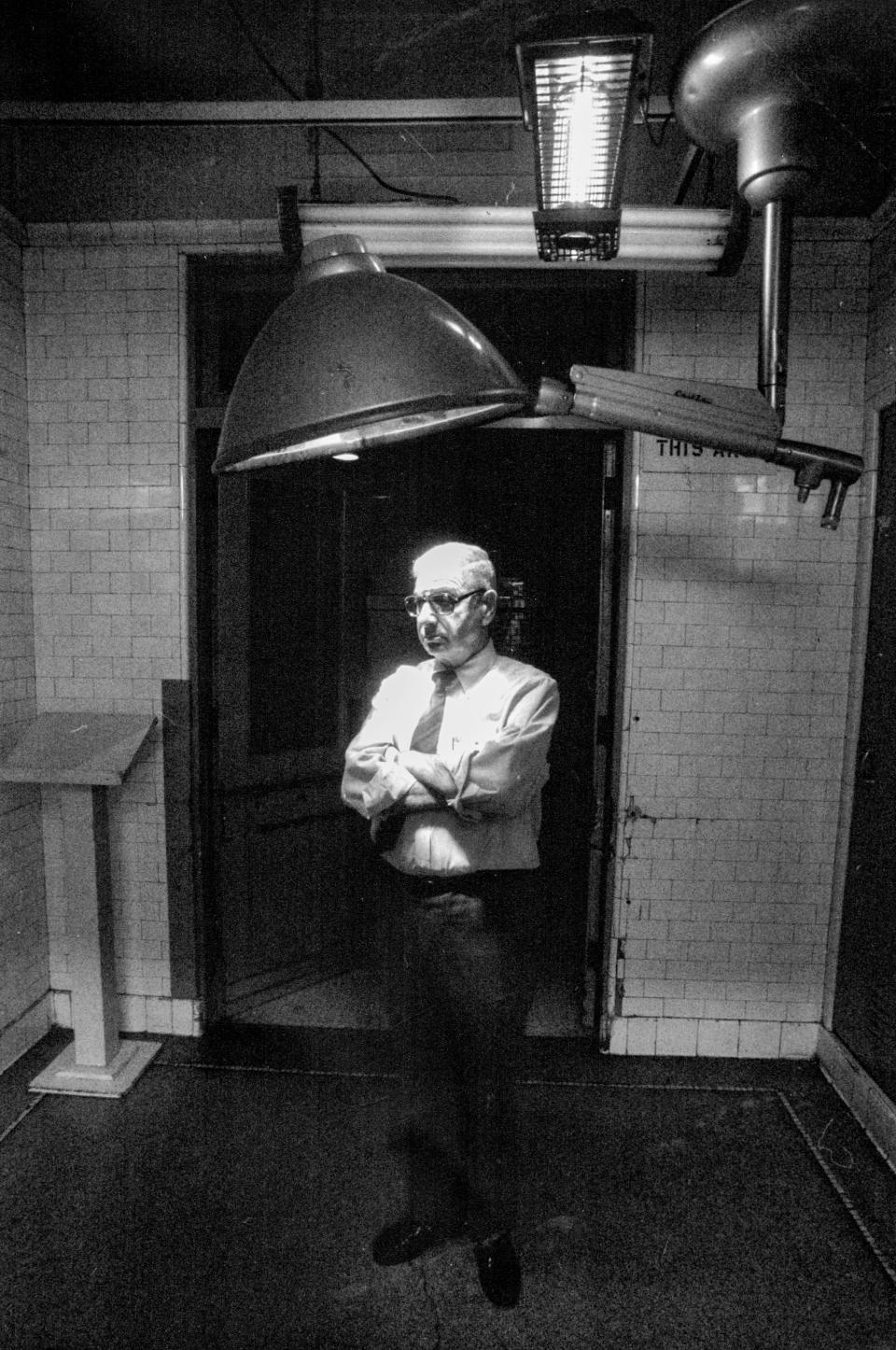

In addition to his work, Werner Spitz squirreled away macabre items for display. They were not, he said in a 1992 Free Press report about his collection, for prurient interest, but as examples of things that he thought could help teach future forensic pathologists.

Spitz said: "We need real examples to show students coming in for residency programs."

"I don't think anyone can understate his impact on forensic pathology," said Dr. Rob Kurtzman, who did a pathology fellowship with Spitz in Detroit the 1980s, working with him for about five years. He called Spitz's contributions to the field "extraordinary."

Kurtzman retired as Montana's chief medical examiner.

"When you study death, finding out why somebody passed away, in some ways, people think you are the voice of the decedent," Kurtzman, now of Grand Junction, Colorado, said. "But through death investigations, you also improve the lives of the living. That's key, and one of the things that Werner imparted."

Private funeral services are pending.

Spitz, who lived with his wife, Anne, also is survived by another son, Jonathan, and a daughter, Rhona, as well as 10 grandchildren, who, the family added, the doctor adored and loved to spend time with — especially in the last years of his life.

In the end, Daniel Spitz told the Free Press, his father peacefully met death.

Contact Frank Witsil: 313-222-5022 or fwitsil@freepress.com.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Dr. Werner Spitz, forensic pathologist, left legacy of studying death