The dinosaur that ate Ryan Zinke

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

WASHINGTON — The dinosaur was a Lythronax, a fearsome predator who lived 80 million years ago. Known as the “King of Gore,” it spent its days feasting upon smaller dinosaurs on the continent of Laramidia. The dinosaur died and so did, eventually, all of its brethren. The land morphed, too, and Laramidia became part of what is today the western United States.

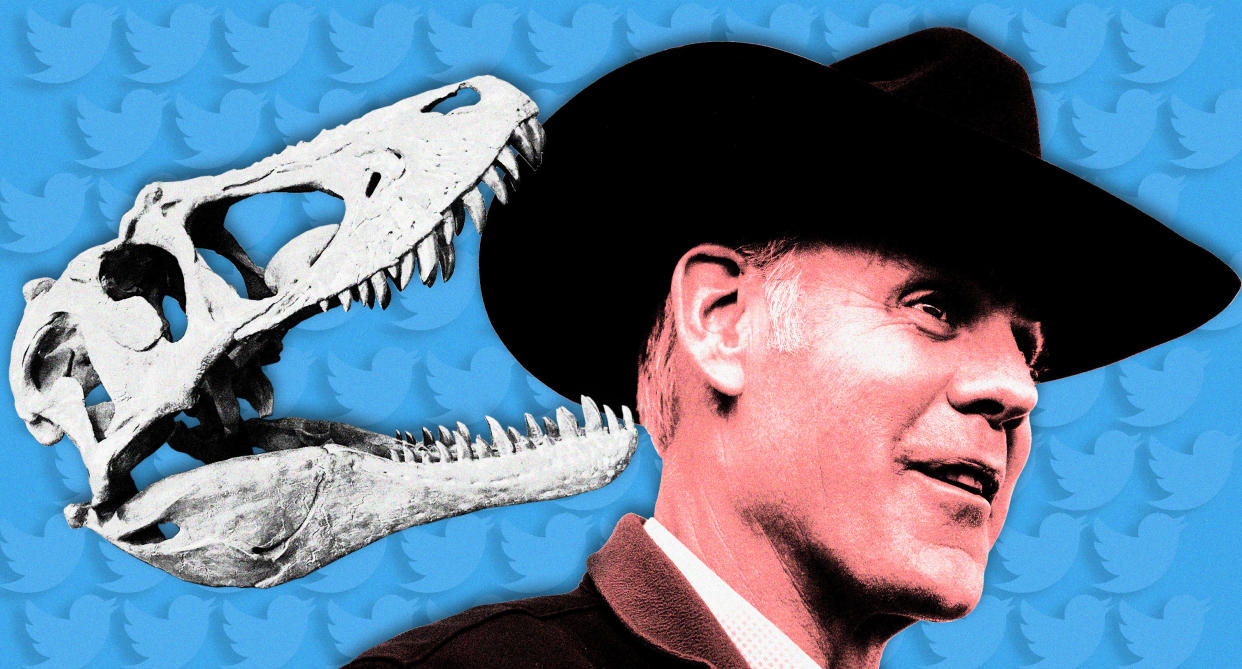

In 2009, the Bureau of Land Management, which oversees federal lands, discovered remains of the long-departed king in Utah, on land that is part of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. A replica of the skull sits in the office of Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, next to a framed picture of Theodore Roosevelt and a tasseled leather notebook, of the sort where one might jot down poetic ruminations while camping out on the high desert of the true West.

Earlier this summer, Zinke tweeted a picture of this well-curated tableau, using the occasion of the latest entry in the “Jurassic Park” franchise to offer a mini-lesson:

Hoping the new #JurassicWorld movie will have a Lythronax. The “King of Gore” was a T-Rex type dino that once roamed the west. This guy was found by @BLMUtah crews in 2009. He currently presides over meetings in my office 🦖 pic.twitter.com/SHL8E4gGQp

— Secretary Ryan Zinke (@SecretaryZinke) June 22, 2018

But if Zinke thought that a dinosaur emoji might curry favor with his audience, he was grievously mistaken.

“That specimen was found in a national monument you shrunk so you could sell mining rights,” one user said. “How dare you display this find when you refuse to protect the ones still in the ground, you pathetic grifter.”

Another critic, in an apparent brevity-is-the-soul-of-wit mindset, offered a one-word riposte: “Scumbag.”

Zinke had long been among President Trump’s most controversial Cabinet members, with the number of ethical scandals plaguing his administration nearly approaching that of Scott Pruitt, the baroquely corrupt administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency who resigned in early July. Zinke’s tweet — and the furious response it engendered — crystalized one of the criticisms of his tenure, namely that he celebrates his own image as a conservationist frontiersman, even as he effectively gives away lands rich with dinosaur remains and archeological treasures to mining companies and other business concerns.

President Bill Clinton designated the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, a preserve in the remote southwestern corner of Utah where the Lythronax skull was found, in 1996 using the American Antiquities Act. Signed into law in 1906 by Teddy Roosevelt, the Antiquities Act allows the president to create national monuments without seeking approval from Congress. National parks, conversely, do require congressional approval.

Bowing to pressure from ranchers, farmers and energy prospectors, Trump has become the first president in modern American history to shrink national monuments designated by his predecessors. In December 2017, he radically reduced in size two national monuments that had been expanded by President Barack Obama. Grand Staircase-Escalante, one of the most fossil-rich areas in the nation, went from 1.9 million to 1 million acres. Bears Ears, spiritually and historically significant to Native American tribes, suffered an even greater diminution, from 1.3 million acres to just 228,000.

Trump announced the cuts in Utah, whose political leaders supported the move, as did others who believed that Obama had overstepped his powers in greatly expanding the national monuments. “These abuses of the Antiquities Act give enormous power to faraway bureaucrats,” he said, “at the expense of the people who actually live here, work here and make this place their home.”

Zinke, a former U.S. representative from Montana who likes to tout his somewhat suspect credentials as a geologist, supported the plan. Several months before Trump traveled to Utah, Zinke prepared a memorandum that identified 10 national monuments for reduction. None of those monuments, critics noted, were in his home state of Montana. These recommendations came in response to an executive order, signed by Trump, mandating a review of 27 national monuments.

And while outrage over the move had been growing for a while, Zinke’s June 22 tweet unwittingly displayed what his critics saw as a manifest hypocrisy. As far as Zinke’s detractors were concerned, the scene featuring Teddy Roosevelt and a dinosaur fossil was celebrating a legacy Zinke had done a great deal to diminish.

Staffers for Rep. Don Beyer, D-Va., noticed the late-June tweet even as much of Washington obsessed over Pruitt’s latest scandals involving used mattresses and expensive moisturizer. “The fossilized skull of a T-Rex ancestor on display Secretary Zinke’s office is exactly the kind of wonder that Department of Interior should be trying to conserve,” Beyer told Yahoo News. “The Trump administration seems oblivious to the fact that cutting Grand Staircase-Escalante in half and selling off our public lands at the behest of industry will have unforeseen and damaging consequences, including failing to protect fossils like the very one on Ryan Zinke’s desk.”

Beyer also noted that the Antiquities Act rollbacks are “possibly illegal.”

Several lawsuits have been filed with the intention of stopping the shrinkage of the two Utah national monuments. Plaintiffs include Native American tribes and environmental groups. “Zinke and his team are talking out of both sides of their mouth,” said Yvonne Chi, a lawyer for Earthjustice, an environmental group involved in litigation against the Trump administration.

It’s hypocritical saying “that national monument protections keep extractive industries out of these lands and at the same time saying that monument protections don’t really do much for priceless cultural sites and scientific discoveries,” Chi said. “Anyone with common sense can see that’s misleading.”

Priceless, in this case, may not be an exaggeration. Grand Staircase-Escalante contains the Kaiparowits Plateau, a shelf of some 1,600 square miles that is home to a smorgasbord of fossils from the Late Cretaceous period, right before dinosaurs went extinct. Twenty-one species of prehistoric vertebrate have been discovered at Grand-Staircase. Bears Ears, to the east, is smaller, but it may host as many as 100,000 distinct archeological sites relating to settlement of this dramatic landscape by the Navajo, Ute and Hopi people, among others.

The Department of Interior says that any worries about stewardship are unfounded. “Clearly the tweet raised awareness for the good work of the Bureau of Land Management’s paleontology experts,” said Interior spokeswoman Heather Swift. As for the criticisms Zinke’s tweet received, Swift argued that “the areas that have the highest concentration of fossils remain within the monuments’ boundaries. This was a key point for the secretary. Additionally, the land that was restored to multiple use from the original boundaries is still federal land and still under federal protection. That means it is illegal to remove fossils and other paleontological and cultural resources from the land without a permit.”

Politicians in Utah have made similar arguments. Speaking several weeks before Trump came to Utah to announce the Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante reductions, the state’s senior U.S. senator, Orrin Hatch, a Republican, said, “We believe in the importance of protecting these sacred antiquities, but Secretary Zinke and the Trump administration rolled up their sleeves to dig in, talk to locals, talk to local tribes and find a better way to do it.”

Critics are unconvinced, given President Trump’s promise to restore the extractive industries, in particular those involved in oil and coal. And those, of course, are fossil fuels — that is, the same carbon matter that sits in replica on Zinke’s shelf. According to one estimate, there are 11.36 billion tons of coal under the Kaiparowits Plateau. Bears Ears, meanwhile, contains deposits of uranium. Unredacted Department of Interior emails inadvertently sent to reporters showed that high-ranking agency officials were determined to downplay the environmental effects of cutting the two Utah monuments while overstating the economic benefits of doing so.

Nor do skeptics of Zinke’s plans believe that the Paleontological Resources Preservation Act of 2009 and other regulations are sufficient to protect the fossils that could be unearthed during activities associated with mining and drilling.

“Opening culturally and paleontologically rich lands to new mining and development is going to lead to damage and destruction of fossil resources which have yet to be identified, much less studied,” said Dan Hartinger, who leads work on national monuments for the Wilderness Society. Estimates based on past surveys suggest that as many as 700 significant fossiliferous sites will be left out of the new Grand Staircase-Escalante Monument.

“It’s bulls***,” said P. David Polly, president of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology and a professor at the Indiana University, in response to the assurances that protections for the Monument’s fossils are as strong as they ever were. “A national monument is a special kind of designation” he told Yahoo News. “It’s there to protect scientific resources.”

Economic activity, he added — whether excavating land or paving it over to build roads or support facilities — will necessarily degrade whatever lessons that land holds about history, whether of humans or dinosaurs or, well, anyone else.

According to Polly, the Lythronax skull whose replica now graces Zinke’s office was part of a fossil found almost directly on the boundary drawn by Trump.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Former Trump official: No one ‘minding the store’ at White House on cyberthreats

How the Land and Water Conservation Fund became a political football

Heat wave strikes the Arctic, and the climate enters the Twilight Zone

Photos: Violence, poverty and politics: Why Hondurans are escaping to the U.S.