A Deep Dive May Have Solved the Mysterious Origin of America's Earliest Language

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A linguistics analysis shows that language arrived in North America in multiple waves from Siberia.

The Americas have half of the world’s linguistic diversity, despite a much shorter human history.

Linguistic typology uses many criteria to compile statistics about world language families.

Humans conclusively did not evolve in North or South America, meaning everyone here arrived from elsewhere. And just as all of the people here must have come from somewhere else, all of the languages must have as well.

In a new peer-reviewed study, linguist Johanna Nichols dug into just that. A pioneer in the field of linguistic typology (a subfield of linguistics that organizes world languages by how many criteria they share from an overall list) Nichols has long been fascinated with the origins of different languages—which, until now, we’ve only been able to study back to about 8,000 years ago in North America.

Nichols wasn’t satisfied with 8,000 years of information, and has believed for decades that using a broader and even more statistical approach than standard methods of linguistic analysis (boosted by computer power) could push our understanding of language further backward in time than ever before.

Her approach—and, thus, the approach of the subfield she helped pioneer—is innovative. Researchers compile lists of qualities that languages have, like whether their nouns have a separate plural form or a gender. They then score different regional languages or language groups on each of those qualities. This allows for the comparison of a number of languages at once, meaning researchers can spot resemblances of many kinds and even overall patterns shared by many languages. And the combination of aspects covered in their spreadsheets creates a more stable model to apply backward in time.

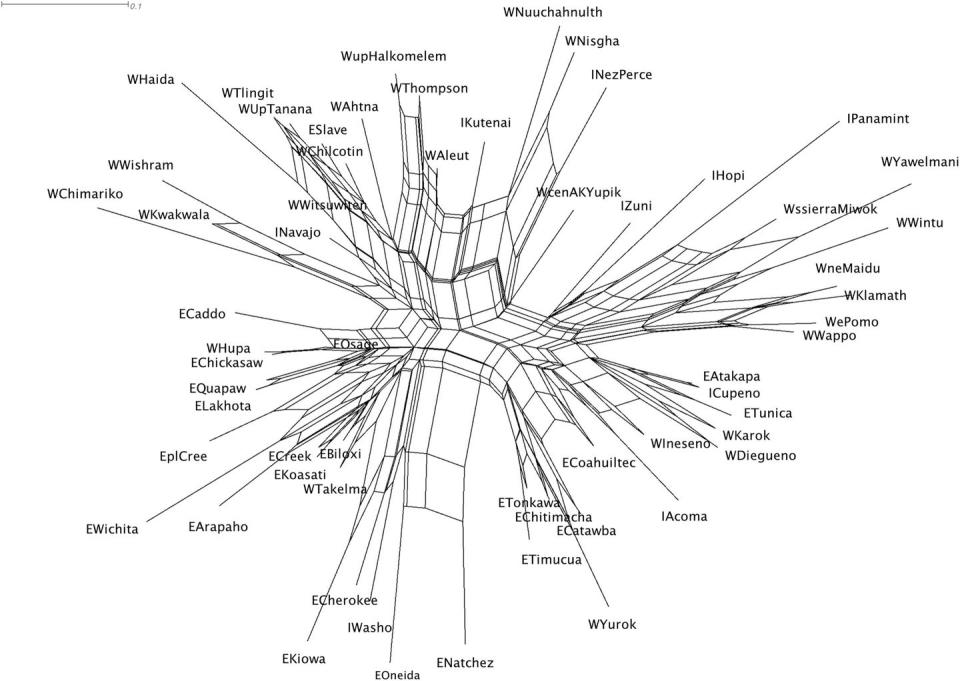

Through those intricate methods of study, Nichols found significant evidence that the first languages of North America can be traced back to two very different language groups from Siberia. She wrote that there are about 200 “independent language families of the Americas,” and that this level of variation must have an explanation based on how people migrated at the time.

Nichols believes it’s likely that such a diverse language pool results from multiple “entries”—paths by which people could enter and migrate within the Americas—both before and after North America was roped off by glaciers. When conditions created physical openings for people groups to travel through, they took advantage and moved.

By analyzing how 60 of those language groups meaningfully resemble or differ from each other, she concludes that people brought languages with them from Siberia in two chunks, about 24,000 and 15,000 years ago. About 14,000 years ago, people were also able to get into the enormous basin formed by the Rocky Mountains in the west and the Appalachian and connected mountain ranges in the east. (This is “intermontane” North America, she explains—between the mountains.)

Certainly, moving the study-able window from 8,000 years to 24,000 years is a huge change—one Nichols wants to see ripple through other fields. “This paper is an exploratory study showing that there is enough linguistic evidence to support the model and raise research questions and hypotheses,” Nichols stated. “It is intended to help geneticists, archeologists, and linguists formulate research questions and hypotheses relevant to each other’s work.”

The nature of language means we will probably never know the exact origin (or many origins) of language as a concept. But innovative analysis like this is a start. Moving forward, Nichols wants to examine where these early North American residents went after arriving in their new home. “Sorting out, in this linguistically diverse population, descendants from the respective openings is a challenge for further research,” Nichols wrote. She’s also curious whether or not the same chunks of migrating people made their way into South America.

Only time—and a great deal more work—will get us as close to understanding language as we possibly can.

You Might Also Like