For decades, Moscow has sought to silence its critics abroad

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

From its earliest days, the Soviet Union's intelligence services — whether known as the Cheka or by the names of any of its successor agencies like the KGB — kept the government in power by pursuing its opponents no matter where they lived.

Intelligence experts say that policy is still followed by Russian President Vladimir Putin, himself a product of the KGB who does not disguise his scorn for perceived traitors, defectors and other political enemies abroad. The Kremlin has routinely denied involvement in such attacks.

The Cheka secret police, founded by Felix Dzherzhinsky, often used assassins to hunt down enemies of the Bolshevik Revolution.

Security expert Andrei Soldatov said the work of the Kremlin's intelligence services, then and now, has been defined by threats from dissidents abroad.

Perhaps the Cheka's most successful undertaking in the 1920s was “Operation Trust,” which focused on Russians living abroad who opposed the regime, he said.

The Trust was a front organization, purported to be anti-Bolshevik but in reality was meant to catch and kill Moscow's enemies. It sent representatives to the West to entrap Russian exiles under the pretext of helping the resistance movement.

That's how it caught Sidney Reilly, a Ukrainian-born agent who worked for Britain both inside Russia and abroad. Known as the “Ace of Spies,” and said to be the model for Ian Fleming's James Bond, Reilly was lured back to Moscow, where he was reportedly killed in 1925.

A look at other regime opponents who fled abroad, believing that exile would keep them safe:

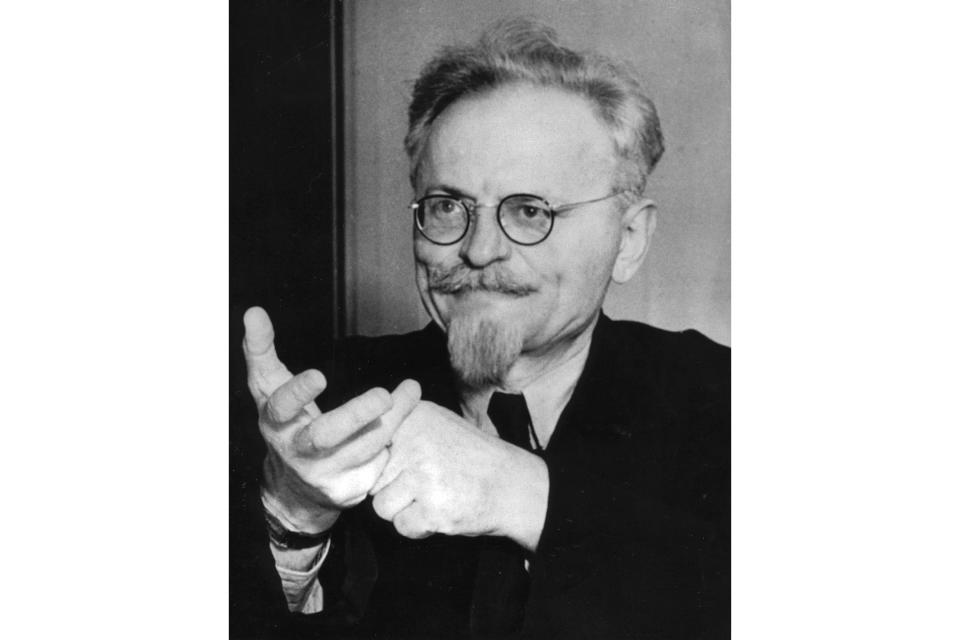

LEON TROTSKY

Leon Trotsky, a key figure in the Bolshevik Revolution and once seen as a likely successor to Vladimir Lenin as leader of the Soviet Union, lost a battle for power with Josef Stalin and fled the country. He lived in exile in Mexico, where he continued to criticize Stalin. He was befriended there by Ramon Mercader, who pretended to be sympathetic to Trotsky's ideas but in reality was a Soviet agent. In August 1940, the two were alone in Trotsky's study when Mercader struck him with an ice ax, mortally wounding him at age 60.

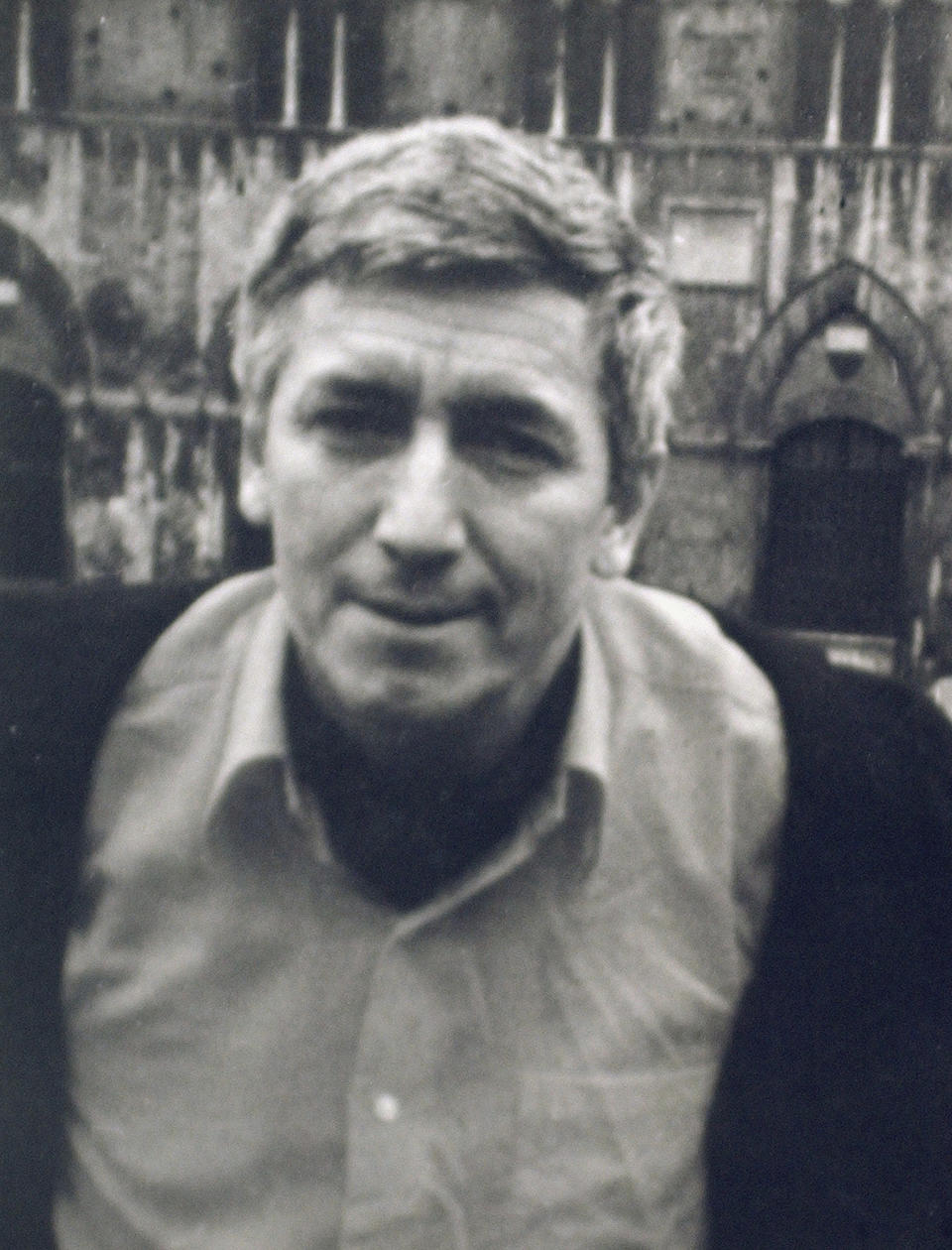

STEPAN BANDERA

Stepan Bandera was the leader of a Ukrainian nationalist movement in the 1930s and 1940s that included a rebel militia which fought alongside invading Nazi forces in World War II. Bandera’s supporters see him as a freedom fighter for Ukraine against Soviet oppression while Kremlin supporters paint him as a Nazi collaborator who massacred Jews. While living in exile in Munich in 1959, Bandera, 50, was killed after being confronted by a Soviet agent with a gun that sprayed cyanide.

GEORGI MARKOV

Bulgarian journalist Georgi Markov defected to the West in 1969 and was a harsh critic of his country's pro-Moscow Communist regime, broadcasting commentaries on the BBC and Radio Free Europe. In September 1978, Markov was waiting at a London bus stop near Waterloo Bridge when a man walked past him and jabbed him with a poison-tipped umbrella. Former KGB agent Oleg Kalugin suggested in 1992 that the attack had been planned by the Soviet Union and Bulgaria, which had asked Moscow for help in the assassination. The probe into Markov's death was closed in 2013 and no one was ever convicted.

ALEXANDER LITVINENKO

Alexander Litvinenko, a former KGB officer and a lieutenant colonel in its successor agency, the FSB, defected to Britain, where he was a harsh critic of the Kremlin and Putin. On Nov. 1, 2006, Litvinenko met two men at London's Millennium Hotel and had tea with them. He later fell violently ill, and doctors determined he had ingested polonium-210, a radioactive isotope. He died three weeks later at age 43. On his deathbed, Litvinenko accused Putin of ordering his assassination, and Britain also alleged that the Russian state was involved. The Kremlin denied involvement.

SERGEI AND YULIA SKRIPAL

Sergei Skripal, a former Russian military intelligence officer jailed for spying for Britain, was released in 2010 as part of a swap for Russian agents caught in the U.S., and settled in Salisbury, England. In March 2018, he and his daughter, Yulia, were found slumped on a bench in the city, with traces of the nerve agent Novichok discovered on the front door of their house. The Skripals spent weeks hospitalized in critical condition before recovering. A British woman died after being exposed to the nerve agent, which was found in a discarded perfume bottle. Britain accused Russia in the attack, which the Kremlin denied being behind, and Western nations expelled Russian spies in response. Two Russian men identified by authorities as the attackers denied any involvement, saying they were only tourists.

ZELIMKHAN KHANGOSHVILI

Zelimkhan Khangoshvili, an ethnic Chechen born in Georgia, fought Moscow's forces during a separatist war in the region of southern Russia. After the war, he continued to help Chechen insurgents, and the FSB viewed him as a terrorist. He fled to Germany after surviving two assassination attempts but was shot to death in broad daylight in 2019 in Berlin's Kleiner Tiergarten park by a bicyclist. Vadim Krasikov was convicted in the killing, which German authorities say was ordered by the Kremlin. Putin has indicated he wants Krasikov returned to Russia as part of a prisoner swap. Khangoshvili is one of several ethnic Chechen exiles killed apparently on Moscow's orders. Evidence reviewed by the court alleged that Krasikov had been employed by a Russian security agency, but Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov called allegations of Russian involvement “absolutely groundless.”

MAKSIM KUZMINOV

In August 2023, pilot Maxim Kuzminov flew a Russian Mi-8 military helicopter to Ukraine, saying he wanted to defect. At a news conference, Kuzminov said he didn't support the war and that Ukraine had promised him money and protection. In October, a popular Russian TV commentator denounced the defection in a report that featured three masked men in camouflage identified as members of military intelligence who threatened Kuzminov, saying he would not live to go on trial. In February, police found what was later identified as Kuzminov's bullet-riddled body in La Cala, Spain. He had been shot a half-dozen times and run over by a vehicle. The head of Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service, Sergei Naryshkin, said Kuzminov became a “moral corpse” as soon as he started planning “his dirty and terrible crime.” Kremlin spokesman Peskov said Feb. 20 that he had no information on the death.