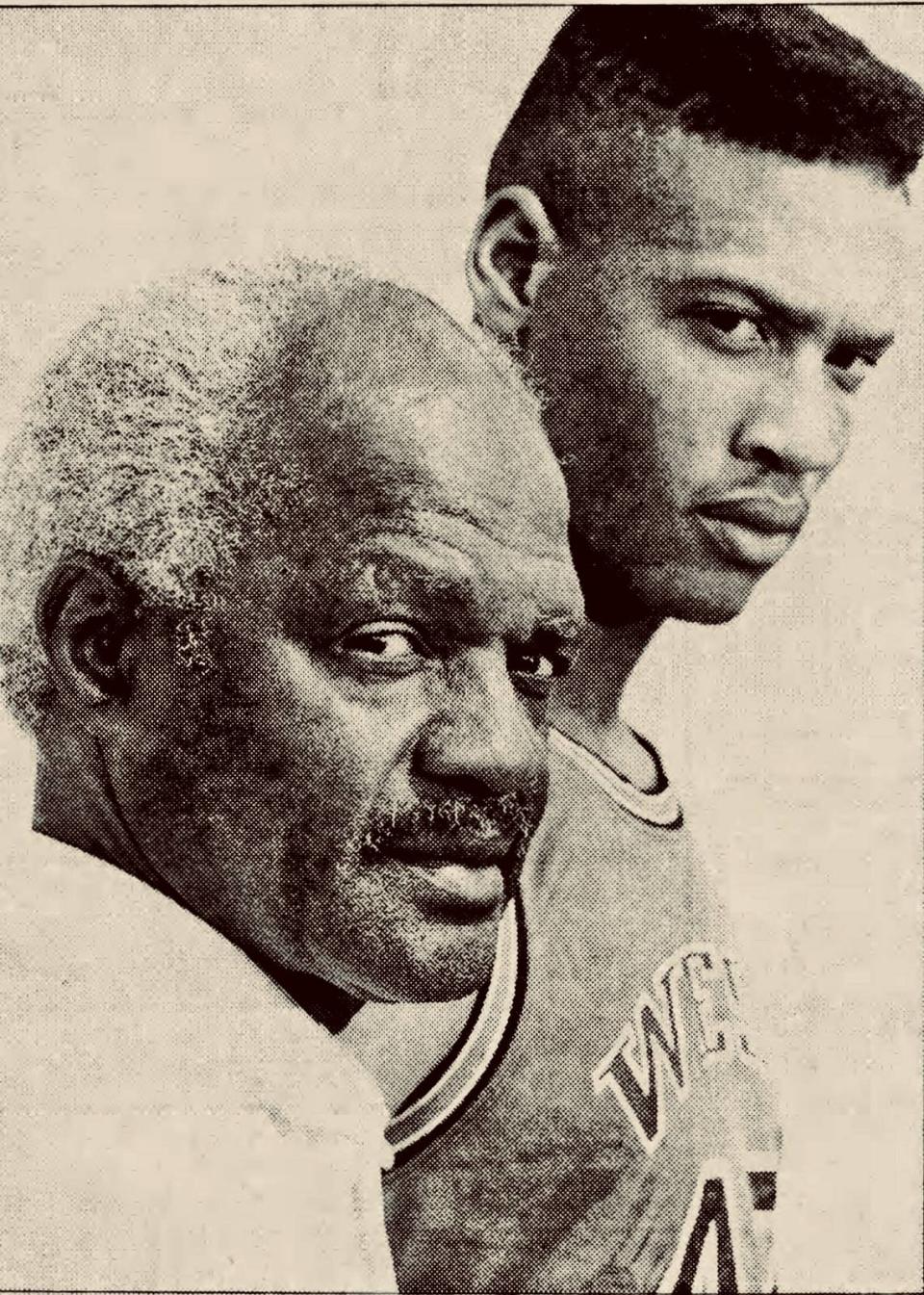

‘The Dean Smith of NC high schools,’ West Charlotte’s Charles McCullough is best in 40 years

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Coming into the 1990-91 school year, West Charlotte High boys’ basketball coach Charles McCullough was a little mad and a little frustrated.

He’d lost his two best players to a burgeoning national power called Oak Hill Academy in Mouth of Wilson, Va.

Power forward Junior Burrough was the reigning Charlotte Observer player of the year and he’d committed to Virginia. Dwayne Forte, a 6-4 wing, would have been one of the best players in North Carolina.

So instead of having a state title favorite, McCullough — The Observer’s pick for the best boys’ basketball coach of the 40-year Sweet 16 era — had a team with five sophomores and six juniors on the roster.

“We’re not worried,” McCullough told The Observer in November 1990. “Do I sound worried? When those kids decided to transfer, I didn’t forget about West Charlotte basketball. People expect West Charlotte to win, and we expect to win this year.”

And West Charlotte certainly won that year.

In December 1990, McCullough became just the sixth N.C. public school high school coach to win 500 games. His team beat East Mecklenburg, 72-67. The Eagles’ coach, Mike Rose, had played point guard for McCullough in the ‘70s.

Later that season, in March 1991, McCullough’s Lions — led by sophomores Jeff McInnis and Thad Bonapart — beat East Wake in the N.C. 4A state championship game.

McInnis left for Oak Hill shortly after that. So what did McCullough do? He took the Lions back and won another state title in 1992, his fifth, upsetting Kinston and a future North Carolina Tar Heels star named Jerry Stackhouse.

West Charlotte become the first back-to-back 4A state champion in 20 years.

“He always showed that he believed in us,” said McInnis, who became a McDonald’s All-American at Oak Hill and eventually played at North Carolina and in the NBA. “The way he coached the game and prepared the players was always with a next-man-up mentality. Like when I left West Charlotte, they won the state title the next year. It didn’t matter who the players were. His system speaks for itself.”

McCullough died in 2017 at age 84, but through his former players, like McInnis, his legacy lives on.

Bonapart was once the Lions’ boys’ basketball coach. McInnis has been a successful high school and travel ball coach who won an Under Armour national title with his Team Charlotte squad in 2015.

McInnis was at dinner last week talking to friends, and McCullough’s name — and philosophies — came up. He said they often do.

“We were talking about how we had to run cross country at West Charlotte back then,” McInnis said. “I mean, no other teams were doing that stuff. People just weren’t doing it.”

Quirky ways, lots of wins

Bonapart said his old coach had lots of quirky ways to get a point across, or to teach a lesson.

Like this one.

At the start of practice in 1990, the year his star players left, McCullough had his team running.

As McInnis said, the first few practices, every year, were like that.

You run. You do aerobics. You play defense.

“We never touched a ball,” said Bonapart.

In the fall of 1990, two Lions — Antonio Bell and a future college and NFL assistant coach named Pep Hamilton — were leaving their teammates behind in distance runs.

McCullough emerged and told the two they were doing so well that they could go into the gym and shoot while waiting on their teammates.

When Bonapart and his teammates finally got back inside, McCullough was also waiting, with a stern warning.

“We came into the gym,” Bonapart said, “and Coach said, ‘As long as you play for me, don’t ever leave one of your teammates. Your teammates are all you have.’

“So we (all) had to run some more.”

Bananas, pancakes and belief

Bonapart said McCullough would always have his teams eat pancakes, bananas and scrambled eggs on game days.

“Coach made us believe in this meal,” Bonapart said. “We believed it gave us extra strength and power. I mean, Coach had competed for a shot in the Olympics and we trusted his background. We thought during the fourth quarter we had an advantage because we had these special meals. It was psychology. Ask anybody now and they’ll die laughing. But we believed it.”

Bonapart said McCullough often told his teams that basketball was like banking.

In preseason, he said, you make deposits into a team account. Then later in the season, in a tight game, McCullough would say the Lions could make withdrawals from their account when other teams were running low.

Over the years, the big comeback, the late comeback, became part of McCullough’s legacy, his mystique.

“I can’t explain it, really,” Bonapart said in 1992. “Sometimes I find myself doing things I can’t normally do. People play for the guy. People want to be here because of Coach. West Charlotte is Coach and Coach is West Charlotte.”

Learning from a legend, becoming a legend

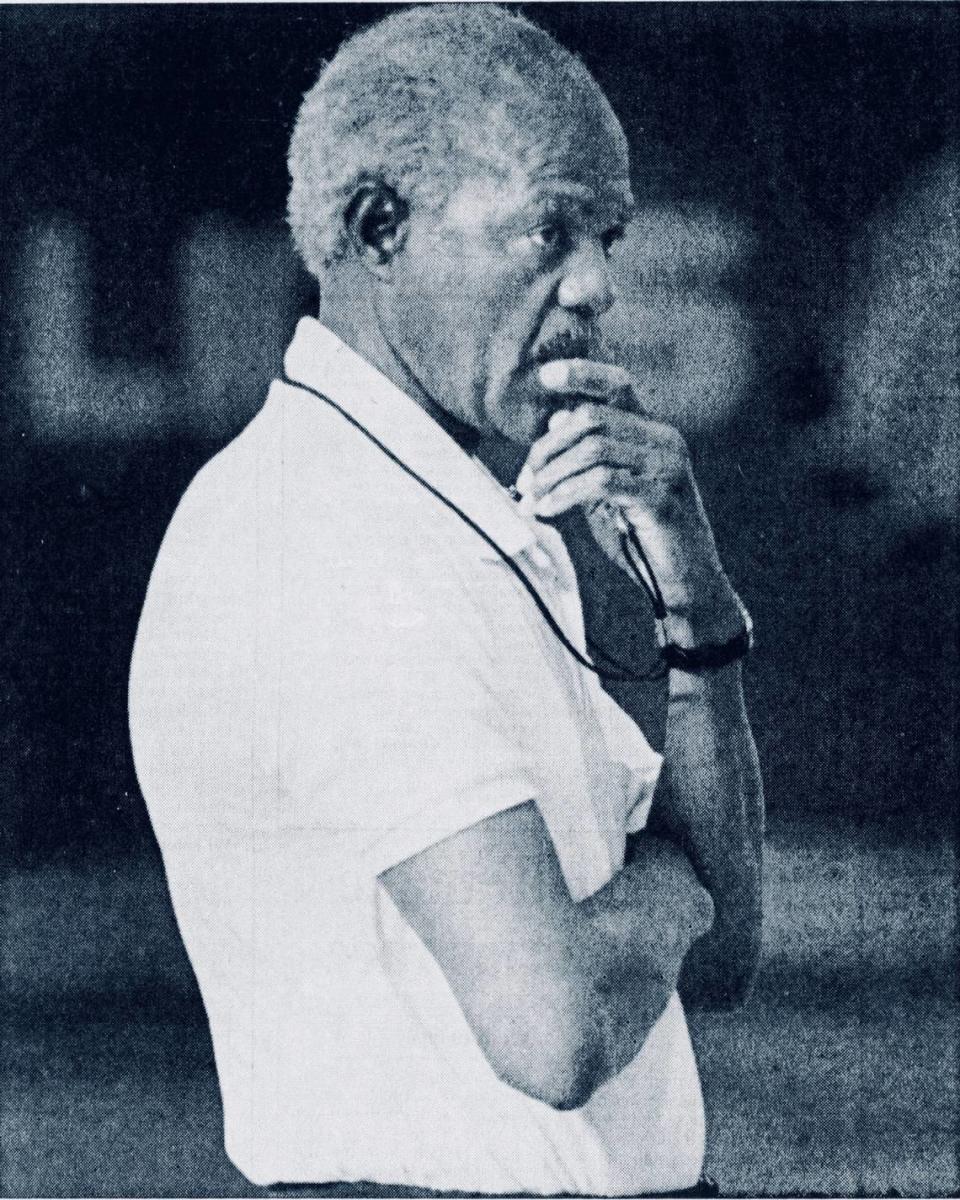

McCullough went to West Charlotte in the 1950s. After he graduated, he went to N.C. Central on a track scholarship. McCullough was undefeated in regular-season high jump competition in 1952 and ‘53. He was second in the 1952 CIAA championships and won it in 1953. The next year, McCullough went to the Army and won the Third Army Championship. When he came back to Central for his final two seasons, he won two more CIAA championships, two NCAA Division II titles and an NAIA national title.

And in 1956, McCullough won the prestigious Penn Relays with a high jump of 6-8 1/2 and competed in the U.S. Olympic Trials.

McCullough was inducted into the N.C. Central Hall of Fame in 1985.

While he was a student there, McCullough also played on the Eagles’ basketball team with a future Boston Celtics star named Sam Jones.

His basketball coach in Durham, a guy from whom McCullough learned a lot of his strategy and tactics, was the legendary John McLendon, who is in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame and the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame.

McCullough graduated from N.C. Central in 1958, and worked for a year at a chemical company in Charlotte because he couldn’t land a coaching job. After one year working, he was hired to coach at Booker T. Washington High School in Columbia, S.C., where he led the team to a 12-6 record. In 1960, he came home and started teaching and coaching at West Charlotte.

He won right away.

In 1968, at 34, his teams were 160-26, including a 21-2 record and a 4A state finals appearance. McCullough was named coach of the year by the old Charlotte News.

Ultimately, McCullough’s teams reached the championship round seven times in 33 years, but from 1986-92, McCullough and his Lions had one of the most dominant runs in NCHSAA public school history.

West Charlotte was undefeated in the 1985-86 season, won the 4A state title and the second Charlotte Observer Sweet 16 championship.

From 1988-93, the Lions made six straight Western Regional, or state quarterfinal, appearances. And West Charlotte won the 1991 and ‘92 state titles, becoming the first 4A team to repeat in 20 years.

“I think West Charlotte is a little intimidating,” former East Mecklenburg coach John Reisterer said in 1992. “They’ve got tradition plus players plus coaches. And if (McCullough is) not a legend already, I don’t know what you have to do. He always wins. The players respect him. I don’t know a coach who doesn’t respect him. He’s the Dean Smith of N.C. high school basketball coaches. Tell me a coach who’s experienced more success, year in and year out, in the largest and most competitive classification in the state.”

Overall, McCullough’s teams won 21 conference championships and seven regional titles. McCullough was named N.C. statewide coach of the year three times. In the summer of 1991, his alma mater, N.C. Central, started the Charles McCullough scholarship.

His record when he stopped coaching high school was 583-255.

“Look, I’m a teacher,” McCullough told The Observer in December 1992. “I like teaching. I think a lot of people forget that. Out here (on the court), they call us Coach, but we’re still teachers.”

Giving college a shot

After West Charlotte, McCullough left for Livingstone College, a Division II HBCU in Salisbury. The Blue Bears were 1-25 the year before McCullough came in 1994 and had a history of struggle.

McCullough was 51-105 in six years, but he started a turnaround at the school. He was CIAA coach of the year after his second season.

McCullough’s team had a scholarship budget of $40,000 and tuition was about $9,000 a year. But he kept working, kept teaching the same lessons he always taught.

In 1998, Livingstone beat St. Paul’s at Winston-Salem’s Lawrence Joel Coliseum. Chanta’ Weathers, a future Hall of Famer at the school, made the go-ahead jumper in the Blue Bears’ first CIAA tournament win.

McCullough and Livingstone made the semifinals that year. It took a while, but in 2014, the Blue Bears won the CIAA title.

That success can be directly traced back to McCullough.

A final touch on a legendary career

Two years ago, West Charlotte renamed its gym for its legendary coach. Bonapart said that was fitting for a man who had coached so many greats, including N.C. Sports Hall of Fame inductee Dwight Durante.

In the 1960s, Durante was one of the first two Black players recruited to Catawba College. He set several scoring records there, including 2,913 career points.

And in the 1980s and 1990s, McCullough coached Burrough and McInnis, who would play in the NBA, as well as Bonapart, who is probably one of the school’s five best players. His coaching tree was large, too, sprouting from former players such as Mike Rose and McInnis to Gosnell “Rusty” White, who built a power at Harding and eventually led West Charlotte to a 1999 state title.

“Playing for Coach was an absolute honor,” Bonapart said. “It was unique and special and it was a brotherhood and it was like its own university. Coach was brilliant. He did all these unorthodox things that we didn’t understand, but we would pull out games no one thought we would because of all those unorthodox things.”

Bonapart still believes that the Lions would have won a third straight state title in 1993 if McCullough had not benched him in a regional game against South Mecklenburg.

“We’re up six and Coach sits me on the bench and does not put me back in the game and we lose,” Bonapart said. “But Coach always said, ‘The way we got there was the way we finished.’”

Bonapart, who later played at Marshall, was drawing a lot of Division I interest. But he was a 6-6 high school center, not big enough to play exclusively inside at the next level. Scouts wanted to see him dribble and shoot, to gauge whether he could play on the wing. So in a big game with scouts in the gym, Bonapart was playing more outside instead of in.

“I was scoring and doing well,” Bonapart said. “But Coach sat me with 3 minutes, 23 seconds (left) and I sat between David Martin and (Tennessee football recruit) Maurice Staley. We talk about it to this day. I was invisible. Coach looked down the bench and looked right past me.

“After the game, Coach says, ‘Thad Bonapart, up until tonight, you were the best basketball player in West Charlotte’s history.’ Talk about destroying me.”

Bonapart laughs, then goes on.

“Honest to God,” he said. “I knew I was not playing how we had been playing, but I had pressure from my father. And man, we would’ve beaten (Duke recruit Jeff) Capel for the state.”

South Mecklenburg eventually lost to Capel and Hope Mills’ South View High in the ‘93 state final.

“I learned a lesson,” Bonapart said. “It’s about team. He said, ‘How did we get here, Thad?’ I love him for that. There’s no one bigger than the team.”

McCullough always said he enjoyed his players, win or lose, and he would often say he wanted them to leave West Charlotte better than how they came in.

Bonapart, now an independent filmmaker in Charlotte, said his story is a perfect example of that.

“You know what makes me the happiest,” McCullough said in 1992. “I like to see my players 10 years later, when they’ve got a family and a job and a career. That’s what I enjoy most. We’re here to build these kids’ futures. The championships and wins are nice, but I like the kids to make something of themselves.”

McCullough’s state title teams

▪ 1963: Led by James Dunlap, Willie Vaughn, James Lilly, William Johnson and Edward Kennedy, the team won the school’s first state championship.

▪ 1966: Finished 19-1, led by three-sport star Daryl Cherry, and won the school’s second state championship.

▪ 1986: Finished unbeaten at 29-0, won state title, set school wins record by beating Raleigh Broughton 67-66 in the final.

▪ 1991: Surprising young team finished 24-3, winning the state title behind sophomores Jeff Mcinnis and Thad Bonapart.

▪ 1992: Team finished 25-5, won the state title and won its last three games by rallying from double-digit second-half deficits.