The dark history behind Hiawatha Indian Asylum in Canton: Looking Back

On May 8, 1897, South Dakota Senator Richard F. Pettigrew introduced a bill on the floor of the senate. Its purpose was to establish “an Indian insane asylum” at Canton. The bill was read twice and passed on to the committee on Indian affairs, which Pettigrew headed. The bill suggested that indigenous people could not be mixed with non-indigenous people with mental health challenges, and that a special government institution would be needed to house and treat them. The bill called for $150,000 to be spent on the facility, $5.6 million when adjusted to inflation. Pettigrew had some trouble getting the bill passed in its original form, but it was eventually attached as an add on to the general appropriation bill, which passed in early 1899.

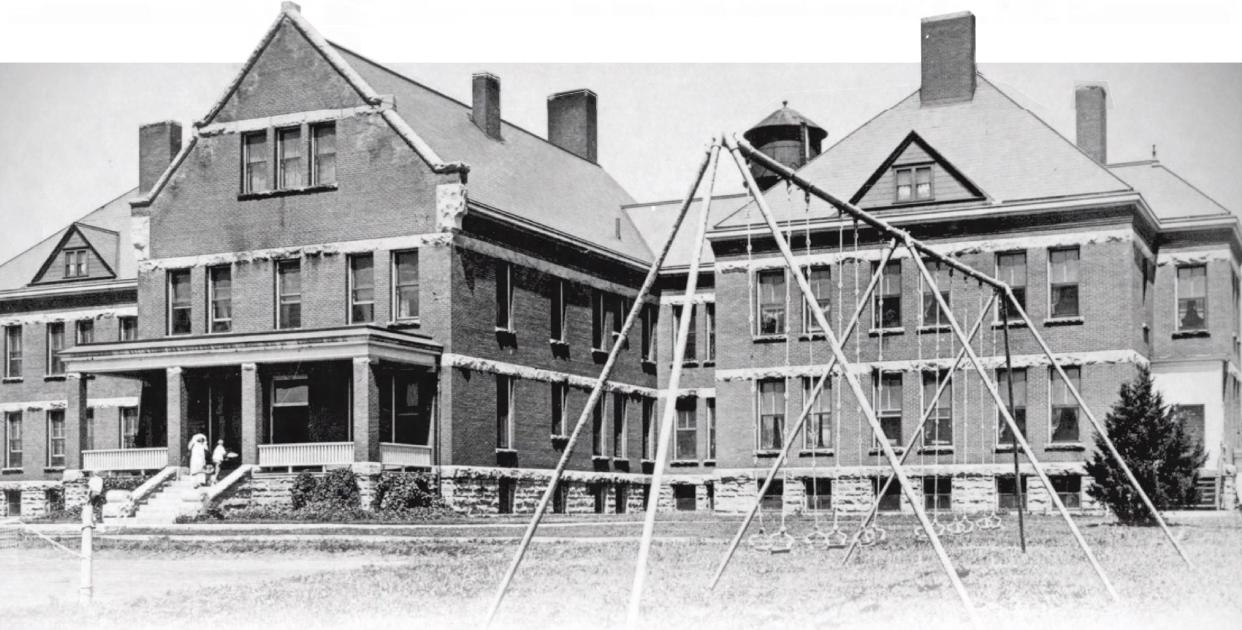

There was excitement in Canton about the expected building boom for the asylum and supporting outbuildings to be constructed on the grounds. It was expected that 500 individuals would be housed at the asylum, and that the federal government would spend $100,000 a year on staff and operations. The amount to be spent in Canton each year was the equivalent of $3.8 million in today’s dollars.

One hundred sixty acres of land were purchased at a cost of $30 an acre to build the asylum and provide space to eventually farm and raise livestock. The location, an eighth of a mile east of Canton, was to be a work farm. Construction was expected to start that summer in hopes that it would be ready by fall, 1902.

Oscar Sherman Gifford was hired as the first superintendent of the asylum. He had no background in health, mental or otherwise, but rather was a lawyer, a judge, a former mayor of Canton, and a former US representative for South Dakota. Dr. John F. Turner was appointed as a physician at the hospital. Turner had formerly worked at the Cheyenne Agency at Eagle Butte.

The first patient received at the asylum, Edward Hedges, arrived on December 30, 1902, though he was described as an inmate. The second patient, named Hon sah sah hah, of the Osage people of Oklahoma, arrived on June 3, 1903. It was said that he was expected to live the rest of his life in the Canton Asylum. He was 24. He died October 23, 1905. Additional patients would arrive in the coming years.

In 1905 ,the name Hiawatha was attached to the institution. Articles were printed across the US about what was to be done about the “insane red man”, with a kind description of gentle rehabilitation experienced by the inmates at Hiawatha. As it turned out, humane treatment was not at all common at Hiawatha.

In 1908, superintendent Gifford was compelled to resign. He was replaced by Dr. Harry R. Hummer, who came directly from St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in D.C., a federal institute for the insane, established in 1855. Around the same time it had been reported that 108 people had been patients at Hiawatha. Of those 108, 22 were cured and released, 23 died, and 63 remained.

Having employed a doctor with a history in treatment of the mentally ill, one would think that the treatment of those in Hiawatha would improve, but that was not the case. Conditions deteriorated under the care of Dr. Hummer. Visitors to Hiawatha, sent to verify good treatment of those held, were shown only the wards that were in the best condition, and not allowed to see what was happening in other wards. In these wards, patients were tied to beds or radiators. Toilets and sinks were removed, so refuse piled up. Sheets and mattresses were grey with coal dust and not often cleaned.

In 1915, Norman Ewing (Flying Iron), who worked at the asylum under Dr. Hummer, filed a report with the Bureau of Indian Affairs revealing the treatment of patients at Hiawatha. For his efforts, he was transferred to another post in Poplar, Montana. In 1926, an investigation found that many held at Hiawatha did not meet the criteria of insanity, and there were recommendations in government to close the asylum.

The gears of government grind slowly, and it wasn’t until 1933 that Hiawatha was closed. Secretary Harold W. Ickes fired Dr. Hummer on October 16, 1933. Hummer tried to file suit to stop the closing and combat the damage to his reputation. Many in Canton who worked at the asylum, provided services to it, or had otherwise profited from its existence protested its closing. The government decided that the remaining patients could be released or transferred to St. Elizabeth’s in D.C. to receive better care for far less expense than keeping Hiawatha open.

All that remains of the asylum today is a gravesite on the Hiawatha golf course. The bodies of over 121 people from over 63 tribes lie in a fenced-off area, their silent repose occasionally interrupted by errant golf balls. Do not forget them, or the inhumane place that put them there, or history will have taught us nothing.

This article originally appeared on Sioux Falls Argus Leader: The inhumane history of Canton's Hiawatha Indian Asylum: Looking Back