D.A. Pennebaker Looks Back at 'Monterey Pop,' Exiting 'Gimme Shelter,' Bob Dylan, and 'The War Room'

In 1967, D.A. Pennebaker and his camera team captured every moment of the Monterey Pop Festival, a joyous celebration of music and good vibes befitting the “Summer of Love.” Fifty years later, that optimism is preserved in Pennebaker’s 1968 film, Monterey Pop, which condenses the three-day music festival into a brisk 80 minutes. Flash-forward to 1969, and the Rolling Stones‘ chaotic performance at the Altamont Free Concert, and you’ll witness the symbolic end of that era just two years later. As captured by documentary filmmakers Albert Maysles and David Maysles in 1970’s Gimme Shelter, the show ended with a concertgoer being stabbed to death by a Hells Angels-affiliated security guard.

It was very nearly Pennebaker, rather than the Maysles brothers, behind the cameras that day, which would have made Gimme Shelter even more of a bookend with Monterey Pop. As the celebrated documentary filmmaker tells Yahoo Movies, the Stones initially approached him to film their performance at Altamont. “We had a deal with the Stones, and I went out to L.A. to spend a week with them,” says Pennebaker, who will celebrate his 92nd birthday in July. “I was living in a little house with them out there, and I didn’t like them! Well, I liked a couple of them, but I didn’t like the attitude they had. I thought they were a little aggressive and mean-spirited. I didn’t want to be around them, so we sort of bailed, and the Maysles took the contract. It’s fine with me; they made a wonderful film and not a film we probably could’ve made as well.”

Heading into a summer where societal tensions seem to be running high, we all could use a little of that Monterey Pop positivity. And in a stroke of good timing, Pennebaker’s film is returning to theaters in a 50th anniversary restored edition that screened in New York on June 14 and now in L.A. on June 19, with Pennebaker scheduled to be in the house, followed by a second screening on June 20. Read on for our conversation with the filmmaker, who talks about Monterey Pop; his Bob Dylan portrait, Don’t Look Back, which also celebrates its 50th anniversary this year; and his 1993 film from inside the Bill Clinton campaign, The War Room.

After the Monterey Pop festival ended, and you were sitting in the editing room with all of your footage, did you have any concept of how you were going to turn it into a feature film?

D.A. Pennebaker: Well, when we brought the footage back to New York, the first thing we did was initiate a week of 24-hours-a day screenings of the rushes to which everybody in the world came, including Ravi Shankar and his guys. There was a roomful of people all smoking pot and watching those rushes, and that was as informative to me as the [footage]. There had been some groups I hadn’t seen at all, because somebody else shot them while I was somewhere else. So it was those screenings where I first really saw what we had. My concept had to do with this broad idea of how this music mattered. You get started editing in a [chronological] line, because that’s how you shot it. After days of rushes, that disappears and you begin to think how does this kind of music start? What gets people interested enough to keep it going? So I started the film with Scott McKenzie’s “San Francisco,” and then let it build from there. When I saw the rushes, I realized that Ravi Shankar was going to be the climax. Nothing could surpass that, and the audience really soaked it up.

One of the things that always strikes me about the movie is its intimacy, from seeing those artists so close to the camera.

Remember, we could only do that because we had these sync cameras that you could carry around on your shoulder. Before that, there was no such thing, so it changed the characteristics of [filming] a festival. If you had the choice of seeing somebody from a distance or being five inches away from their face, there’s no question of which one you’d want to look at. We were able to bridge that distance, and it made a big difference, but also, I could get on stage. I was on stage with Janis Joplin, and watching her give herself over to the music was just as important as watching her sing it. We had not seen that kind of singer in a long time.

At that time, like today, the public image of certain stars was often heavily manufactured. But the singers you were filming — Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix — didn’t seem to project that. Did they have a concept of how they’d be depicted in your film?

It was not their problem, it was our problem. And we didn’t even know we had a problem until we started mixing the paint, as it were, to see what you can do and what you can’t do. There were certain musicians that were friends of mine, and that I liked and knew very well, and I just assumed that, because I was making the film, that I could have them in the film…. I began to see that certain music — while it was music that I liked and it was good music — it didn’t work in the kind of [film] we were making. It’s like poetry; you can’t have many bad lines, or people will stop reading. And a couple of those musicians were not bad lines, they just were the wrong lines, so they had to go. So, it sort of resolved itself, but it was interesting how it did it. I was surprised, and I was not sure exactly how, but I knew when we did it right that you could tell it was right, and that was the most important thing.

You mentioned that one of the reasons you turned down the Altamont assignment is that you didn’t enjoy spending time with the Rolling Stones in between their performances. How important is it for you to like the people you are filming?

Well, that was also because a lot of the footage would have been back in the hotel room, and they’re busy throwing furniture out of the window. So I thought, “That’s not the kind of [movie] I’m looking for!”

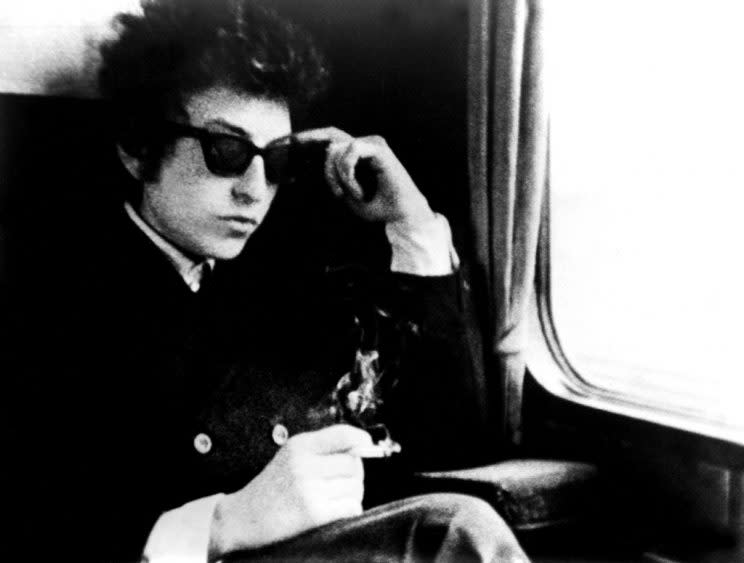

Did you feel a more personal connection when you were following Bob Dylan around Europe?

That was different. With Dylan, Albert [Grossman, Dylan’s manager] came to ask me if I wanted to go to England to do a film, and I didn’t know much about Dylan at all. Maybe I’d heard one song, whatever was playing on the radio. I didn’t know what he was like, but he was a musician, and I was ready to do a film about a musician. I think the film that Albert wanted me to make was a musical film that would help them promote Bob when he came back from his concert tour. After about three or four days in London, hanging out with them, I began to hear Dylan as a person. It wasn’t that he was a smart-ass or anything. He had kind of a naïve quality but he used language in a way that was interesting. I was interested in this guy and what he says as much as the music. He struck me as a poet, and I wanted to film a poet in the making. I had read a book about Byron, and he had a quality where he existed totally above whatever the momentary history was. He was part of a wider history, and I thought, “[Bob] is like that.” I wanted to make a film that, 100 years from now, people will want to watch just because there’s no other way to see him.

So we cut the music stuff very short. Later on, a guy who worked for me said, “You know, you’ve made the wrong film,” and brought me all the music, saying “Take a look at this.” Some of those songs are real poetry, like “Don’t Think Twice.” It’s just fantastic. So we made a different film [2007’s ’65 Revisited], and I love that one, too. But the first film is still legitimate, because 100 years from now, people will be watching it. The music they can probably get on a disc or something; they won’t need to look at a film.

To me, there’s a direct line between Don’t Look Back and how stars use social media outlets like Instagram today. That idea of allowing a camera to provide access into their lives. Only today, they’re often the ones wielding the camera, rather than an outsider like yourself.

You know, what was unique about that film, is that I wanted to make a film all by myself, the way you’d write a novel. I had a person who was a friend of Dylan’s who knew how to use a Nagra [a portable sound device], and she’d do the sound sometimes. But sometimes, I was there by myself; there wasn’t anybody else. I would just put the Nagra in the middle of the room, and that was the sound. And now that idea of making a film by yourself — that’s happening all over the world! What you could put down on a piece of paper, you can now put down on a piece of film.

Do you recognize the Dylan you filmed in the Dylan who recently accepted a Nobel Prize?

I heard his Nobel speech. I’m not surprised he got that. He earned it! Anybody who can get that many people stirred up about what he puts down on paper or on a record, he gets a place at the table. We’re still partners [in Don’t Look Back]. It was a handshake deal; no agents or lawyers or anything. With Dylan, it was 50/50, and it still is.

Do you think he’ll ever release Eat the Document, the Don’t Look Back “sequel,” covering his 1966 tour of England with the Hawks?

Eat the Document was a mess. Everybody had a go at it. Robbie [Robertson, frontman for The Hawks, who later became The Band], had a go. Nobody knew how to edit film, [or] really got much of a take on it, so it was a mess from the start. It passed from hand to hand, and nobody was going to take it seriously. But there’s some incredible material in that film and, eventually, it will see the light of day. Bob Neuwirth [Dylan’s tour road manager] made our version of it, “You Know Something’s Happening,” which is about an hour long. Eventually, that’ll be shown. I don’t worry about those things. It’s Dylan’s film not mine, and whatever he wants to do with it, that’s his business. Time is what always controls these things, not anybody. As somebody once said, “The evolution of the world depends on funerals!” [Laughs] Eventually, everybody gets to see everything.

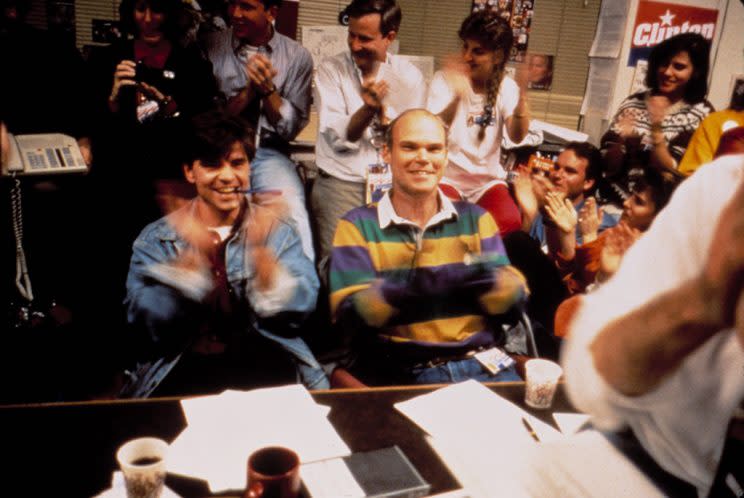

Twenty-five years after Monterey Pop, you were on the ground filming another major historical event, Bill Clinton’s 1992 Presidential campaign for The War Room. Did observing them at that point help you glean any insight into Hillary Clinton’s campaign in 2016?

What I saw is the problem that people are going to have ever making a film like that again. It wasn’t just getting permission; you can probably always get permission, especially if you’re related to somebody. They don’t like you being there with a machine that can record what you hear, and we had to hear everything everybody said. When we went down to Little Rock to meet James Carville, we didn’t know who he was. We thought he was somebody’s drunken relation! [Laughs] He’s eating popcorn and drinking beer, and said, “What do you want?” I said, “We want to just hang out with you here until the election.” He asked, “Why should I let you do that?” When somebody asks you a question like that, the only answer is, “Because we want to.” We went back to our motel, and about an hour later, he called us and said, “Come in.” From then on, we were part of that group.

Did witnessing that election style from such a close vantage point ruin any illusion you might have had about politics?

I’ve never gotten to a place where I think the whole thing is a scam; it’s a dangerous and tricky game because the stakes are so high, and there’s hardly anything else in your life, at least in this country and maybe in Russia, where the stakes are as high. I feel that politics is just an aspect of a life on the planet that’s difficult because there’s so many of us, and it’s changing so fast. Up until now, all that we are has been determined by evolution. That’s changing, and I know it is because we’re researching a film on it right now. I think we’re going to have evolution by medical determination; people are going to go in and change your DNA. That’s going to happen because people want to live longer and, in order to live longer, you probably have to change what kind of person you are. It’s going to be a different world, and politics is what we have that reflects that.

Politics are probably driven by forces that are reasonable, can be understood and are not in themselves evil. You could look on the nomination and the authorization of Trump as being a bad thing to happen to the country, and in a sense it is because he’s incompetent. It’s like having your 5-year-old drive your Ferrari. It’s a terrible waste! But in the end, after the Ferrari gets totaled and you have to go back to bicycles, you’re probably thinking better than you did before. We have to find a way to search, because it’s hard to find. Only poets, writers, and maybe musicians ever come close to finding it. That’s why I think that, in their way, they’re all saints.

Watch D.A. Pennebaker’s new introduction to ‘Monterey Pop’ restored version:

Read more from Yahoo Movies: