Could Alabama IVF decision have embryos owning property, newborns on Medicare? | Opinion

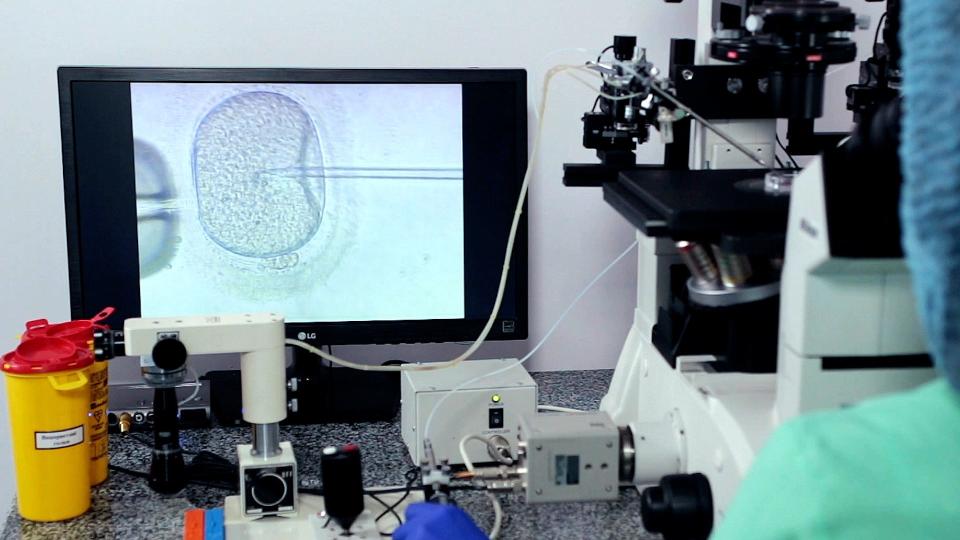

Newspapers around the country have decried the recent opinion by Alabama’s Supreme Court holding that embryos conceived by in vitro fertilization – “extrauterine children” or “embryonic children” in the court’s words – are legally people from the moment of conception. These articles have emphasized the dilemma the decision creates for would-be parents who have already frozen embryos or planned to do so.

But the court’s opinion indirectly raises many other legal issues it appeared not to contemplate and commentators have not yet recognized, issues the state legislature’s recent makeshift response largely overlooks. For starters, many couples prepare wills in which they leave some or all of their property to their children. Others die without wills, in which case state intestacy laws achieve a similar result. How will these rules of descent apply in Alabama after the court’s decision?

Will embryos inherit late parents' property?

Imagine a couple who gave birth to fraternal twins using in vitro fertilization, leaving a half-dozen other embryos to be implanted, donated or destroyed later. If that couple dies, their property most likely will pass to their eight (under Alabama’s interpretation) children, meaning that three-quarters of their estate will now be owned by embryos. Any sale, lease or mortgage of the property will require the consent of all eight owners. Granted, courts regularly appoint guardians to represent the interests of minors in similar settings. But every minor attains majority or dies within 18 years; embryos, by contrast, may need guardians forever. A growing share of Alabama’s property will be held by offspring that reside in freezers, perhaps forever.

Under Alabama’s interpretation, these embryos are people from the day the doctor introduced sperm to egg, giving them a strong argument that they are U.S. citizens upon conception. Their parents can presumably claim them as dependents on their federal and state tax returns. They would have to be enumerated in every census after they are conceived, and their numbers would count toward congressional representation, but only as long as they remain in Alabama.

If an embryo is successfully implanted 21 years after conception, would that newborn immediately be eligible to drive, purchase alcohol and cigarettes, marry, acquire a firearm, join the military and vote? They would look like infants but might legally be the same age as their siblings born 21 years earlier.

What if one of these younger siblings chooses to move to a state that rejects Alabama’s definition of personhood? Would this daughter be 39 in Alabama but 18 in New York? Similar problems arose before the U.S. Supreme Court recognized same-sex marriage, when couples who married in states that acknowledged these unions relocated to jurisdictions that did not, only to discover they were forfeiting spousal health care benefits and the power to make end-of-life decisions for each other.

Welcome to the world! And Social Security!

If that embryo is implanted 65 years after it is formed – which will likely occur at some point, given that the current record appears to be 30 years – that person could be eligible for Medicare and Social Security from the moment the doctor cuts her umbilical cord. Rather than receiving retirement benefits for a couple of decades, these youthful-looking seniors might collect for all the years they are breathing, a variation of Medicare for All that Alabama’s justices surely did not intend to implement.

These questions are not fanciful. Similar cases arose after the first in vitro babies were born, some conceived after their biological fathers had died. Courts struggled with whether these babies were eligible for Social Security: They deserved sympathy and support, but Social Security denied their claims, having not budgeted for these posthumously conceived children. The rules developed in earlier times never contemplated these modern questions and do not apply tidily to these unanticipated disputes. Even one of Alabama’s justices conceded that science is “outdistancing the law in various areas, especially in the context of human reproduction.”

The Alabama Supreme Court had a point it wished to make, and it did so with resounding clarity. One of the concurring justices referred to embryos as “little people” and observed that “human life cannot be wrongfully destroyed without incurring the wrath of a holy God, who views the destruction of His image as an affront to Himself.”

But by reaching the conclusion it did, the court opened up countless other issues beyond the obvious question of whether parents should enjoy the autonomy to make difficult familial decisions for themselves. These questions and others will inevitably arise, with one justice foreseeing “unfortunate consequences stemming from today’s decision that no one intends.” The Alabama court has offered no guidance to the judges and legislators who will have to wrestle with them when they do.

Gregory M. Stein is Professor Emeritus of Law at the University of Tennessee College of Law.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: Opinion: Alabama short-sighted about repercussions of IVF decision