A constitutional fight is brewing in Menendez’s corruption trial

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

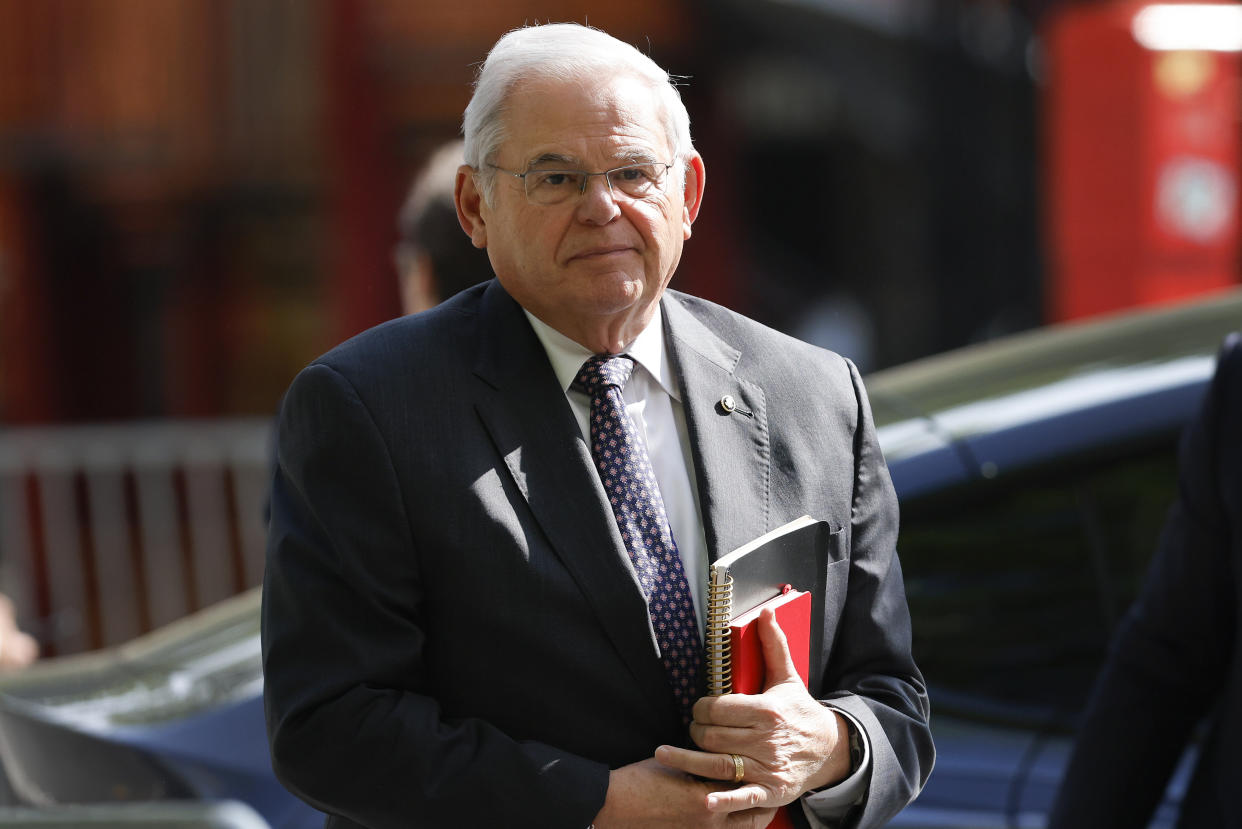

The federal judge overseeing Sen. Bob Menendez’s corruption trial could soon blow a hole in prosecutors’ ability to prove their central claim: that he took bribes to help send billions of dollars of American military aid to Egypt.

Menendez’s attorneys are arguing that some of the most damning evidence against him cannot be shown to jurors without violating lawmakers’ constitutional “speech or debate” privileges. Now prosecutors worry a pending ruling by Judge Sidney Stein could create a class of “super citizens” in Congress who are above the law.

Stein is considering whether jurors can see text messages and phone records that prosecutors say will show Egyptian officials were “frantic about not getting their money’s worth” and Menendez’s wife boasted about her husband’s influence over arms sales.

The constitutional fight has been brewing for months and will come up again and again during Menendez’s trial, which started last week and is expected to last through June.

Menendez is charged with accepting bribes, including cash and gold bars, from a pair of New Jersey business people who hoped he would use his perch atop the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to help Egypt get American military aid and arms.

Prosecutors are already having to dance around some of Menendez’s Senate actions because of the Constitution’s speech or debate clause. It grants a form of immunity to lawmakers that is mostly impenetrable in investigations relating to the official duties of lawmakers, their aides or other congressional officials.

Stein has rejected Menendez’s attempt to have the whole case thrown out. He ruled, citing precedent, that the constitution doesn’t protect promises lawmakers make in exchange for bribes.

So while prosecutors can talk about alleged promises, they still can’t talk about legislative acts themselves. That means the case is already convoluted. They could show evidence, if they have it, that Menendez promised to do something in exchange for bribes — but not show evidence about whether he actually did the thing he promised.

In this case, the fight is over whether Menendez took bribes to help Egypt obtain billions of dollars in military aid, which faced obstacles in the Senate, including holds placed on the funding by senators with power over aid and arm sales.

Prosecutors are trying to show jurors texts they believe show Menendez did this while defense attorneys are trying to exclude some of the same evidence, which they say is protected by the Constitution.

“I understand this may be more challenging for the government to prove its case,” Menendez attorney Avi Weitzman told the judge during an argument without jurors present. “We’ve said from the beginning that government cannot prove the case they promised.”

Potential confusion for jurors

In Weitzman’s view, the government can introduce evidence of a promise, but they cannot introduce activity that the senator takes in “putting a hold, or lifting a hold, or someone else asking about a hold that he put on or didn’t put on, in an effort to prove a corrupt agreement that we believe never existed.”

Paul Monteleoni, one of the prosecutors trying Menendez, agreed in part about the legal standard in the Constitution.

“But,” Monteleoni told Stein, “it is also not designed to make members of Congress super citizens immune from all criminal responsibility.”

Attorneys are already being forced to resort to hypotheticals in court that could soon confuse jurors, if they haven’t already. This week, for instance, a former State Department official called as a witness gave lengthy testimony about Egyptian arm sales but only barely mentioned Menendez because of the speech or debate restrictions.

Jury confusion could increase as future witnesses will be unable to talk what Menendez did or didn’t do while taking legislative action.

In coming weeks, prosecutors plan to refer to language from a news article about a hold Sen. Patrick Leahy put on arm sales to Egypt that Menendez uses in an email to his now-wife, Nadine. But even though Leahy is a former senator, his actions are also protected by the speech or debate clause. So in front of the jury, attorneys plan to refer to Leahy as “not Menendez” or a pseudonym.

Stan Brand, a former counsel to the House of Representatives who has argued a bunch of speech or debate cases, said the notion that the constitutional clause walls lawmakers off from accountability is wrong, but prosecutors being allowed to introduce privileged evidence creates grounds for Menendez to appeal.

“They are tying themselves in knots and if the judge sustains it, it’s going to put a big hole in their case, and if he doesn’t, Menendez is going to have a great appeal,” Brand said.

Prosecutors face a gauntlet of constitutional issues to convict Menendez and make it stick. The speech or debate issues are separate from the challenge presented by what counts as an “official act” following a Supreme Court ruling that overturned former Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell’s conviction. The high court found that “setting up a meeting, calling another public official, or hosting an event does not, standing alone, qualify as an ‘official act.’”

So, on the one hand, legislative acts that are clearly official acts cannot be talked about directly; and on the other, actions that are not legislative acts — like a Menendez call trying to brush back a USDA inquiry into a friend’s Egyptian meat monopoly — may not be deemed significant or substantial enough to qualify as official acts.

Key text messages for prosecutors

There are at least two slices of Egypt-related evidence that the defense wants Stein to keep from the jury on speech or debate clause grounds. Prosecutors have called the evidence “critical” to parts of their case.

First, prosecutors say they have a Sept. 9, 2019, text message from an Egyptian official to one of the business people accused of bribing Menendez that shows Egypt worried that Menendez put a hold on “a billion dollars” in aid to the country. According to prosecutors, the business person, Wael “Will” Hana, then tried to reach Nadine, who was dating Menendez at the time. Hana then called Fred Daibes, another business person accused of bribing Menendez. Daibes called the senator and then called Hana. Within minutes, Hana texted the Egyptian official saying Menendez said it wasn’t true that he’d put a hold on the aid.

Prosecutors also said they have “great evidence” that they know they can’t use about what really happened. According to prosecutors, after Menendez got this inquiry, he went to talk to a staffer who placed the hold and told her to lift it.

The second piece of evidence is a January 2022 text message that Nadine sent Hana with a link to an article she received from the senator about pending foreign military sales totaling $2.5 billion. “Bob had to sign off on this,” she wrote, according to prosecutors.

Monteleoni said the text implied Menendez wanted to let Egypt know to “keep the bribes flowing, and he is going to keep giving you what you want on the military aid.”

Menendez and his co-defendants, Daibes and Hana, have all pleaded not guilty.

Attorneys for Menendez have portrayed his actions to aid Egypt as consistent with long-standing American interests. Since the 1978 Camp David Accords, which brokered peace between Egypt and Israel, Egypt has been the No. 2 recipient of American military aid — second only to Israel.