Chief Family Court judge strikes down challenge to magistrate deciding divorce case. What it means.

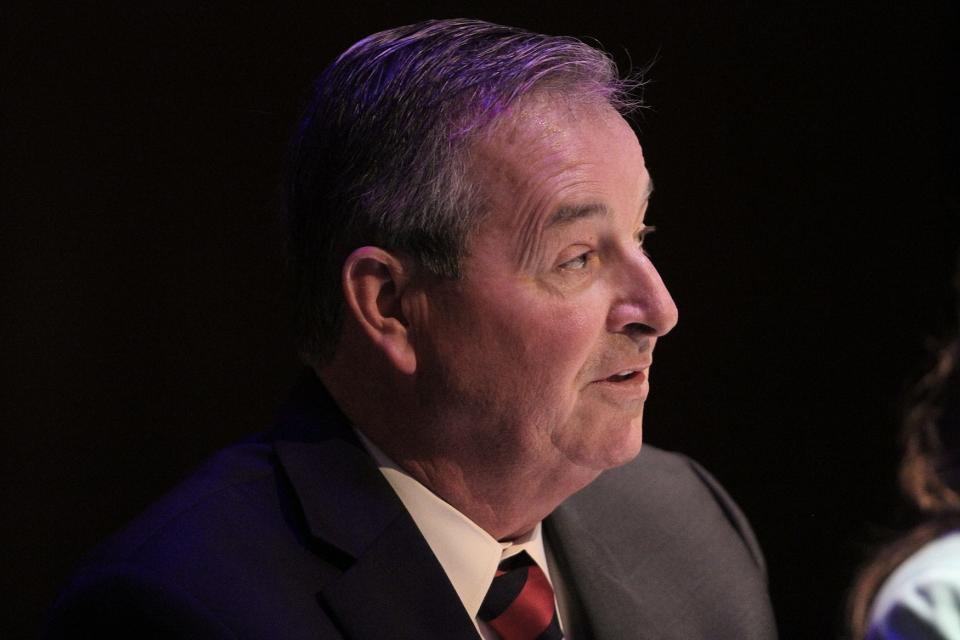

PROVIDENCE – Family Court Chief Judge Michael Forte on Wednesday struck down a father’s challenge to having a magistrate oversee his divorce case, not a judge.

Forte rejected James Florio Jr.’s appeal of General Magistrate Daniel V. Ballirano’s refusal last month to transfer the Florios’ divorce case to a judge. The ruling came as state lawmakers consider legislation that would explicitly empower the chief judge to assign Family Court magistrates to hear contested divorces.

Florio had argued through his lawyer, Evan M. Kirshenbaum, that state law does not allow magistrates to preside over contested divorce cases. Florio cited, too, that decisions by a magistrate must be first appealed to the chief judge before the state Supreme Court, an extra step that forces the parties to exhaust more time and money.

Forte found that a chief judge’s decision to assign a magistrate to a particular calendar, as he has with Ballirano, was in keeping with his powers under state law.

“An assignment to try contested divorce cases does not create a judgeship. The assignment of a general magistrate to the contested divorce calendar does not and could not bestow lifetime tenure, the salary range of a judge of the family court or other powers or benefits of a family court judge,” Forte wrote.

Forte, however, decided that he would preside over further proceedings in the Florios’ case. Samantha Florio filed for divorce in December 2022. The couple have a child and the case has been hotly contested.

Legislation to allow magistrates to hear trials

Forte’s ruling comes amid a legislative push to have magistrates perform the same duties as judges, presiding over and deciding contested divorce cases.

At Forte’s request, identical bills were submitted in the state House and Senate that would authorize the chief judge to assign Family Court magistrates to hear contested divorces. Both bills were heard by their respective Committees on the Judiciary and held for further study.

“As you might expect, contested cases take much longer to resolve," Forte wrote to the House Judiciary. "I believe that the more judicial officers who hear these cases, the more likely the cases will be settled short of a lengthy trial.”

The legislation was submitted the same day the state Supreme Court issued a ruling in which it declined to take up a legal challenge questioning a Family Court magistrate’s authority to decide a contested divorce case. The ruling upheld a decision by Ballirano.

“Our position has consistently been that the statute provides the chief judge with the authority to assign any of the magistrates to any calendar that will assist the court in fulfilling its mission,” Forte said.

More: Should magistrates oversee contested divorce cases? Why Common Cause RI is objecting.

The difference between judges and magistrates

Family Court currently has 11 magistrates and 12 judges. Under state law, magistrates are selected by the chief judge of the court with the advice and consent of the state Senate. They sit for 10-year terms that can be renewed.

State law empowers magistrates to hear juvenile justice and child custody matters, such as temporary placement, custody and adoption, as well as to enter divorce decrees.

The salary range for the Family Court magistrates is $176,503 to $211,803, according to a courts spokeswoman. Forte’s most recent magistrate picks were made with the assistance of a Family Court Magistrate Selection Committee.

Judges must go through a public interview and hearing process before the Judicial Nominating Commission. The Commission then forwards the names of three to five candidates to the governor as possible nominees for the lifetime posts. Family Court judges have a salary range of $188,249 to $225,897.

Forte indicated there would be no increases in salaries or benefits for the magistrates for the increased duties.

Opposition by Common Cause Rhode Island

Common Cause Rhode Island opposes the legislation and argues that if magistrates are going to perform the same role as judges, they should be subject to the same selection process and be vetted by the Judicial Nominating Commission.

“If Family Court magistrates are allowed to conduct trials, they should be chosen in the same manner that Family Court judges are selected – through the Merit Selection process. The court cannot have it both ways – arguing that magistrates should be selected in a different manner from judges but granting those magistrates the same powers as judges,” John Marion, executive director of the good-government group, wrote to the House Committee on the Judiciary

Magistrate positions are viewed by good-government advocates, like Marion, as a stepping stone to a judgeship and a run around of the merit selection process for judges approved by Rhode Island voters in 1994 after scandals.

According to Marion, state lawmakers began exploiting the magistrate loophole almost immediately, with numbers ballooning from a mere handful performing administrative functions to dozens.

“Supporters of the Merit Selection system, including Common Cause Rhode Island, pointed out that magistrates are judges in all but name and therefore should be subject to the same selection process as all other judges,” Marion said. He continued “Yet supporters were told time and again that magistrates are not judges because they do not conduct trials.”

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Family Court ruling could pave the way for RI magistrates hearing divorce trials