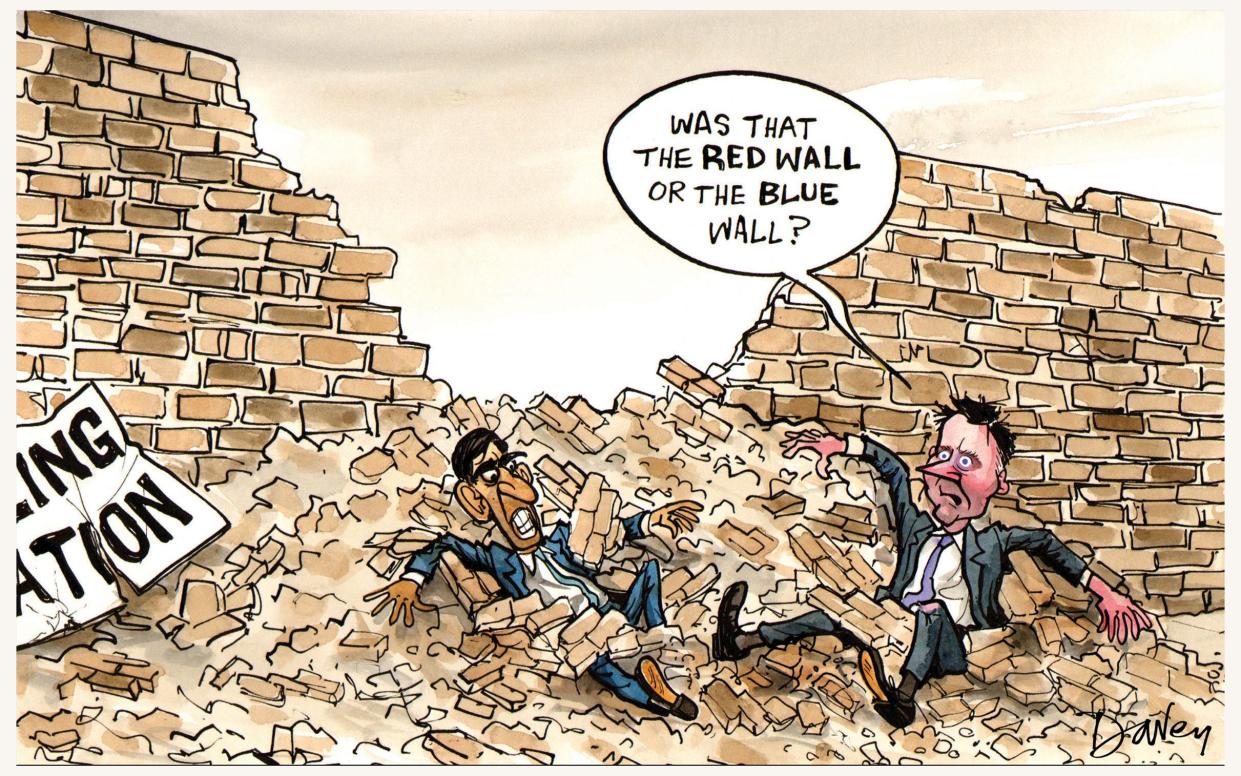

Changing leader will not save the Conservatives: the two-party system can’t be bucked

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Did you know that Labour got a lower vote in Thursday’s Blackpool South by-election than in the same constituency in the Conservative landslide general election of 2019? Yet it lost then and won now.

The reason, of course, was the turnout. In 2019, it was a little over 56 per cent. This week, it was 32.5 per cent. This does not lead me to argue that Labour did not do well on Thursday night in Blackpool, or in most of the country in the local elections. Even less does it lead me to claim that the Conservatives, despite Ben Houchen’s victory in Teesside, did all right. But it is of some interest that only 10,825 Blackpuddlians voted Labour and yet they were enough to make up 59 per cent of those voting.

Turnout is often low at by-elections, but the Blackpool South result contrasts with that in Wirral South in February 1997, the last by-election before Tony Blair’s New Labour chucked out the Tories in May of that year. There, Labour gained the previously Tory seat in a turnout of 71.5 per cent, more than double the Blackpool South percentage.

Which is a long-winded way of saying that Labour, though well into the phase of winning seats, has not yet done the same for hearts and minds.

A fair summary might be that, after 14 years, voters feel the Conservative Party has delighted them long enough, but they have not yet decided exactly what to do about it. The options available to them now include Reform, and also – probably more attractive to most – doing nothing at all and staying at home.

It was a by-election which led me to break the habit of a journalistic lifetime. Three years ago this Monday, in Hartlepool, the Conservative candidate gained the “safe” Labour seat, taking over half the vote (on a turnout a third higher than in Blackpool South). I suggested then, only slightly tentatively, that this result might mean the death of Labour.

My point was that Sir Keir Starmer, the man brought in to rescue his party from the depths to which it had sunk under the extremist Jeremy Corbyn, was almost equally unattractive to voters. This second-referendum Remainer had little more to offer Red Wall voters than did Friend-of-Hamas Jeremy, I wrote. Sir Keir seemed to have got precisely nowhere.

I should have stuck by one of the only two sensible rules about British general elections, which is that it is extremely hard to break the two-party system. (I’ll come to the other sensible rule in a minute.) So long as we have first-past-the-post elections, voters will naturally incline to a binary choice between the centre-Right and the centre-Left.

After a bit, the floaters will get fed up with whichever lot they have put in and turn them out, putting in the other. Each of the two main parties will quite often suffer internal convulsions, but in the end, enough of them will stay together to survive. The splittists will fail.

This has been the pattern throughout the history of our parliamentary democracy. The cast changed a century ago when one of the two main parties – the Liberals – fell and was replaced by Labour; but the binary system quickly re-established itself.

Almost as soon as I had made my post-Hartlepool mistake, Covid aftershocks and Boris Johnson himself began to undermine the success of Boris Johnson, creating an opportunity which Sir Keir, without panache but with doggedness, took.

Three years on, and people are talking instead about the death of the Conservative Party. I do not propose to repeat my mistake of 2021. Although I have never seen the Tories in a worse mess than they are today, and although we are almost certainly entering a Labour era, I think it highly unlikely that Britain will end up without a Conservative Party.

The Reform Party, you see, is not a phenomenon in its own right. It is what doctors call an epiphenomenon, a secondary symptom.

It may well attract some Labour votes that the Conservatives could never win, but the fundamental reason it exists is because the thing called the Conservative Party is in a bad way. The natural effect of our system is that, after a period of defeat, a mainstream party rethinks, revives and the cycle continues.

In the years since the political death of Margaret Thatcher, we have had the Referendum party, Ukip and the Brexit Party, later renamed Reform (forgive me if I have forgotten a few others along the way). Collectively, they have made some difference. Nevertheless, none has succeeded. The Tories have been in power for 21 of those nearly 34 years. If the Conservatives reflect on this cycle, they will see they can only make it worse by trying desperately to break it.

The year 69AD was known as the Year of the Four Emperors. Galba, the successor of Nero, was murdered by Otho in January. After defeat at the hands of Vitellius in April, Otho committed suicide. In December, Vitellius was killed by a mob. Vespasian took over.

I need not labour comparisons with the Empresses Theresa and Liz, the Emperor Boris and his trusted Treasurer Rishi, who somehow contrived his fall. I simply make the point that those Tory legions who think it would be fun to install yet another emperor must be crazed by bloodletting. Look at the atavistic yearning for Penny Mordaunt as leader among some party members. It is caused by little more than the thrill at seeing her carry that Coronation sword.

Unlike in the Roman Empire, we have general elections. And while our system has never insisted that every prime minister must first win a general election before holding office, none can enjoy the full confidence of his/her MPs and the electorate unless he has been victorious at the ballot box.

Part of the contempt the public now feel for the Tories derives from the sense that we have been impotent witnesses to a series of mini-coups d’etat in which one faction gains brief, almost worthless mastery over another. The reign of Liz Truss was the apotheosis of this.

What the plotters seem never to appreciate is that victory in these battles does not necessarily command wider consent. The Tories’ unhappy mixture of MPs’ votes and party members’ votes needed to choose the leader makes it possible for victory, even when won according to the rules, to lack the necessary buy-in from colleagues. For voters, it gives the maddening impression that the Tories think they own the freehold of government.

There may well be a widespread longing to get rid of Rishi Sunak, but it is ridiculous to suggest that he is the central obstacle to another Conservative victory. Besides, at this stage, the only people entitled to do the deed are the voters themselves. As I write, we do not know the results in London or the West Midlands, but it would seem that Lord Houchen’s victory has stilled the party clamour for Mr Sunak’s head.

I promised to mention the other sensible rule about general British elections – as opposed to local, mayoral elections or by-elections, which tend to exaggerate. It is that their results are always deserved, including the ones that seem inconclusive.

On present showing, the Tories seem to deserve to lose, but Labour does not seem to deserve to win. Which seems to suggest that there is a good battle still to be had.