Campus protests are part of an enduring legacy of civil disobedience improving American democracy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

They didn’t illegally camp out in local parks or on college campuses, as many protesters did across the U.S. recently. But back in 1773, the Boston Tea Partiers broke the law when they protested British Colonial taxes by throwing tea into Boston Harbor.

As protests drawing attention to the humanitarian crisis in Gaza have spread, there has been criticism from a number of quarters. Many of these critics speak of a right to protest and to free speech but denounce any breaking of laws. Some have alleged “outside agitators” are involved, using that in an attempt to justify the use of police force to break up the demonstrations, including student protests on college campuses.

It is easy to confuse the sometimes diverging concepts of peaceful protest and law-abiding protest. In most cases, it’s reasonable to expect that groups of protesters will abide by the law. But there are times when doing so diminishes the effectiveness of the protests.

In high-stakes situations, it can be morally permissible to choose to peacefully break certain laws in order to raise awareness of greater injustices. It’s called civil disobedience. And it’s part of a long-standing American tradition going at least as far back as the Boston Tea Party. It also includes the abolitionist and suffrage movements of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the civil rights and anti-war movements of the 1960s and 1970s, and a number of more recent social-justice movements this century, including Occupy, the opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline and Black Lives Matter.

As a moral and political philosopher, I believe it is important for citizens to understand the role civil disobedience can play in checking abuses of power and nurturing democracy.

Nonviolence is key

Civil disobedience involves accepting the rule of law in general while simultaneously breaking a specific law. As philosopher Peter Singer writes in his book “Practical Ethics,” “Those who engage in civil disobedience demonstrate the sincerity of their protests and their respect for the rule of law and fundamental democratic principles by not resisting the force of the law, remaining non-violent, and accepting the legal penalty for their actions.”

To be clear, when protesters engage in civil disobedience, they are not breaking laws that prohibit violence. The laws they decide to break are either discriminatory in nature or outlaw comparatively minor actions to act as barriers to organized dissent. For instance, people break local laws that prohibit tent encampments or other gatherings on public land.

Crucially, civil disobedience does not involve the use of weapons. The protesters are not putting the life or safety of other people in direct risk. But there are plenty of examples of people engaging in civil disobedience who are met with government violence that endangers the lives and safety of protesters.

For instance, police beat civil rights marchers crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965, and National Guard troops shot students protesting the Vietnam War at Kent State University in 1970. Police also attacked Native Americans and others protesting construction of the Dakota Access oil pipeline and, most recently, police have beaten and pepper-sprayed college students protesting Israeli violence in Gaza.

Ancient origins

The first example of civil disobedience in the Western philosophical tradition dates to the 399 B.C. trial and execution of Socrates, an ancient Greek moral philosopher. As described in the writings of Plato, Socrates was tried and officially found guilty of impiety as well as of corrupting the young. This was likely due, in part, to his criticisms of Athenian democracy as they are reflected in Plato’s writings.

When given the opportunity to plead for exile, Socrates accepted execution rather than agreeing to cease his public philosophizing in Athens. His decision has inspired countless other stands of principled dissent since.

Modern adoption

A key figure in the U.S. tradition of civil disobedience is the naturalist and philosopher Henry David Thoreau. In his 1849 essay on civil disobedience, originally titled “Resistance to Civil Government,” Thoreau asserts the principle that a person’s moral conscience is endangered by complying with unjust institutions.

He argues that individuals are not always obliged to subordinate their moral convictions to the law. Thoreau wrote his essay after being jailed for refusal to pay taxes. He believed those taxes supported slavery and the Mexican-American war. His arrest came soon after the U.S. began that war, a conflict Thoreau considered an unjustified land grab that would serve to strengthen slaveholding states.

Thoreau spent only one night in jail before a relative, much to his annoyance, paid the taxes Thoreau owed. But his essay influenced thinkers and reformers worldwide, including Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, resistors of fascism during World War II and Martin Luther King Jr.

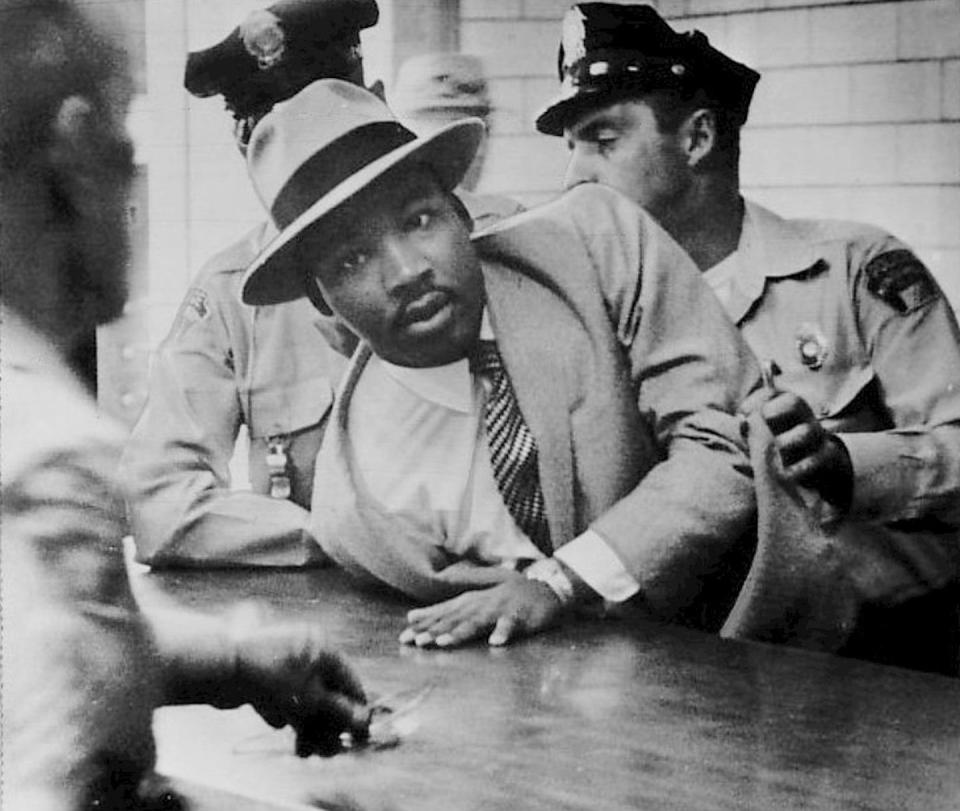

In his 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” King, who himself was perceived to be an “outside agitator” by critics of the anti-segregation movement in Birmingham, outlined what could be considered a handbook for civil disobedience. When he wrote it, he was in jail for “parading without a permit.”

King advocates for negotiation first. If that fails, he says, it becomes necessary to prepare for the consequences of civil disobedience. This includes serious preparation for enduring violent reactions against nonviolent protest, for instance from police or the National Guard. Finally, King advocated planning the direct action for a time that would create the most tension. As King wrote:

“(T)here is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth. Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half truths … The purpose of our direct action program is to create a situation so crisis packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation.”

It works

The approach Socrates chose, the Boston Tea Partiers adopted, Thoreau explained and King detailed has worked in recent weeks at a number of universities in the U.S. and around the world. Some university administrations have agreed to talk with protestors and to begin efforts to meet their demands.

Unfortunately, those examples of constructive protest and negotiation have gotten much less media coverage than when university administrators decided to suspend students and call in police to clear out protesters.

But those who use force in the face of civil disobedience would do well to reflect on Thoreau’s criticisms – including his lament that most authorities prefer escalating a crisis:

“(I)t is the fault of the government itself that the remedy is worse than the evil. … Why does (government) always crucify Christ, and excommunicate Copernicus and Luther, and pronounce Washington and Franklin rebels?”

Thoreau proposed that authorities take a different approach, to “anticipate and provide for reform … cherish (the) wise minority … encourage its citizens to be on the alert to point out its faults, and do better.”

It is likely they could find a copy of Thoreau’s essay as well as Plato’s dialogues and King’s letter in their campus libraries, and perhaps in some of those student protesters’ tents.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Lawrence Torcello, Rochester Institute of Technology

Read more:

‘Uncivil obedience’ becomes an increasingly common form of protest in the US

New wave of anti-protest laws may infringe on religious freedoms for Indigenous people

Lawrence Torcello does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.